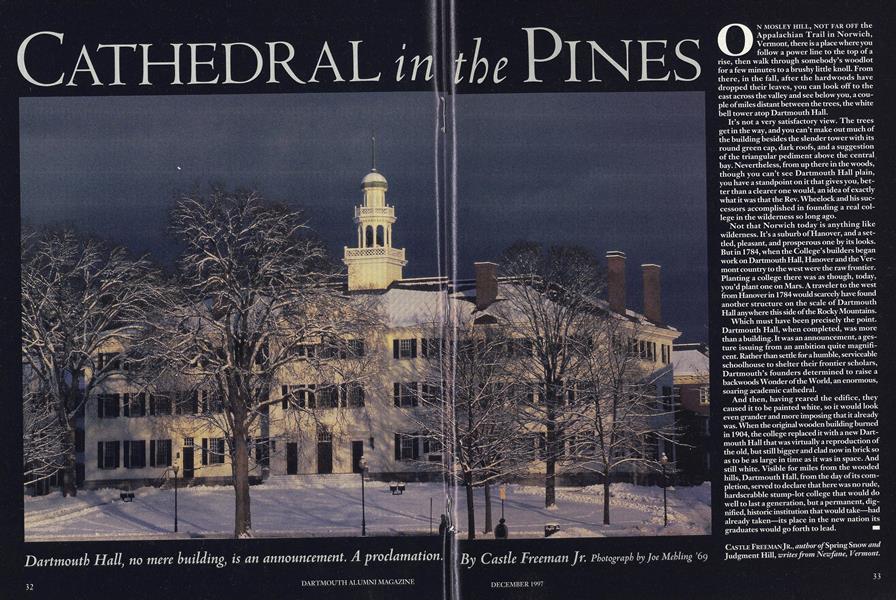

ON MOSLEY HILL, NOT FAR OFF the Appalachian Trail in Norwich, Vermont, there is a place where you follow a power line to the top of a rise, then walk through somebody's woodlot for a few minutes to a brushy little knoll. From there, in the fall, after the hardwoods have dropped their leaves, you can look off to the east across the valley and see below you, a couple of miles distant between the trees, the white bell tower atop Dartmouth Hall.

It's not a very satisfactory view. The trees get in the way, and you can't make out much of the building besides the slender tower with its round green cap, dark roofs, and a suggestion of the triangular pediment above the central bay. Nevertheless, from up there in the woods, though you can't see Dartmouth Hall plain, you have a standpoint on it that gives you, better than a clearer one would, an idea of exactly what it was that the Rev. Wheelock and his successors accomplished in founding a real college in the wilderness so long ago.

Not that Norwich today is anything like wilderness. It's a suburb of Hanover, and a settled, pleasant, and prosperous one by its looks. But in 1784, when the College's builders began work on Dartmouth Hall, Hanover and the Vermont country to the west were the raw frontier. Planting a college there was as though, today, you'd plant one on Mars. A traveler to the west from Hanover in 1784 would scarcely have found another structure on the scale of Dartmouth Hall anywhere this side of the Rocky Mountains.

Which must have been precisely the point. Dartmouth Hall, when completed, was more than a building. It was an announcement, a gesture issuing from an ambition quite magnificent. Rather than settle for a humble, serviceable schoolhouse to shelter their frontier scholars, Dartmouth's founders determined to raise a backwoods Wonder of the World, an enormous, soaring academic cathedral.

And then, having reared the edifice, they caused it to be painted white, so it would look even grander and more imposing that it already was. When the original wooden building burned in 1904, the college replaced it with a new Dartmouth Hall that was virtually a reproduction of the old, but still bigger and clad now in brick so as to be as large in time as it was in space. And still white. Visible for miles from the wooded hills, Dartmouth Hall, from the day of its completion, served to declare that here was no rude, hardscrabble stump-lot college that would do well to last a generation, but a permanent, dignified, historic institution that would take—had already taken—its place in the new nation its graduates would go forth to lead.

Dartmouth Hall, no mere building, is an announcement. A proclamation.

Castle Freeman Jr., author of Spring Snow and Judgment Hill, writes from Newfane, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

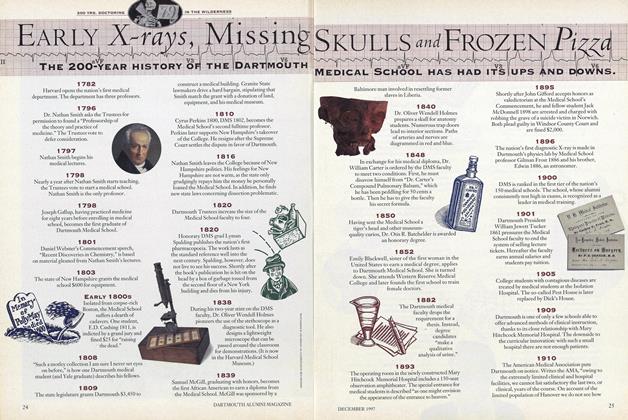

FeatureEarly X-rays, Missing Skulls and Frozen Pizza

December 1997 -

Cover Story

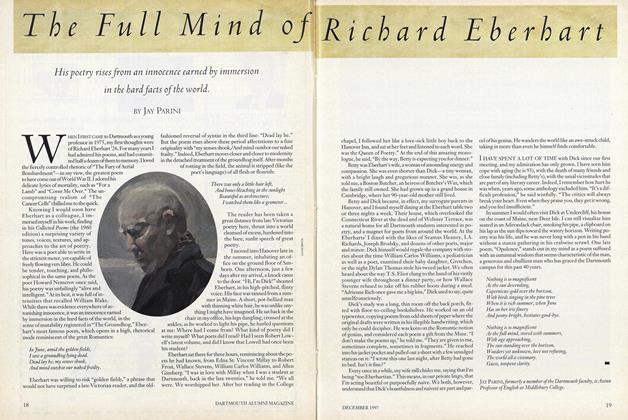

Cover StoryThe Full Mind of Richard Eberhart

December 1997 By Jay Parini -

Feature

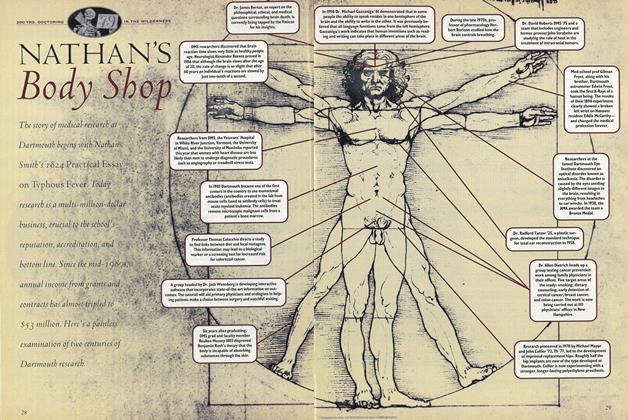

FeatureNathan's Body Shop

December 1997 -

Feature

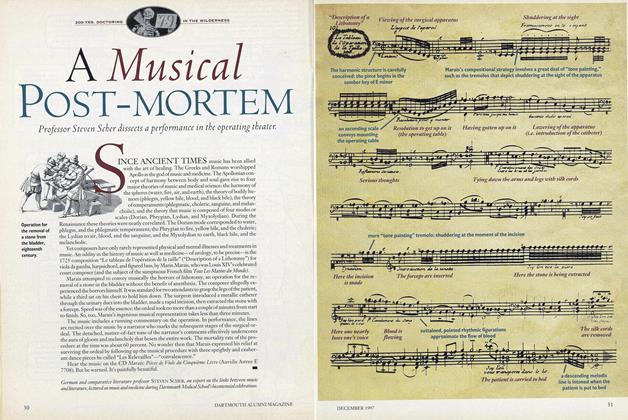

FeatureA Musical Post-Mortem

December 1997 -

Feature

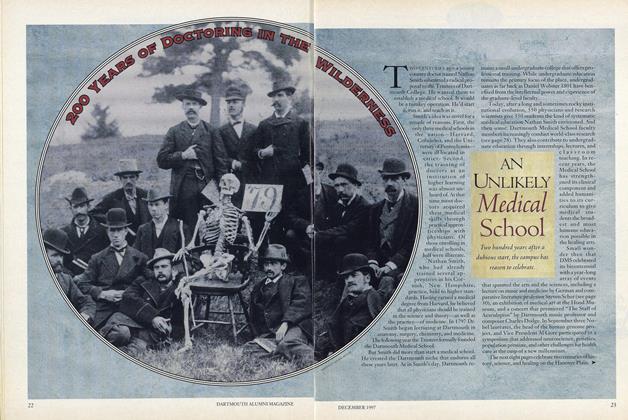

FeatureAn Uulikely Medical School

December 1997 -

Article

ArticleStars & Streep for Autumn

December 1997 By "E. Wheelock."

Castle Freeman Jr.

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryTamara Northern

OCTOBER 1997 -

Cover Story

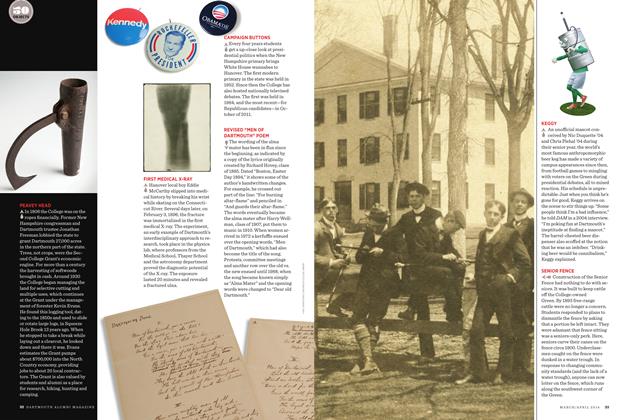

Cover StoryFIRST MEDICAL X-RAY

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

Feature1923 – Great Class of a Great College

JULY 1973 By Charles J. Zimmerman '23 -

Feature

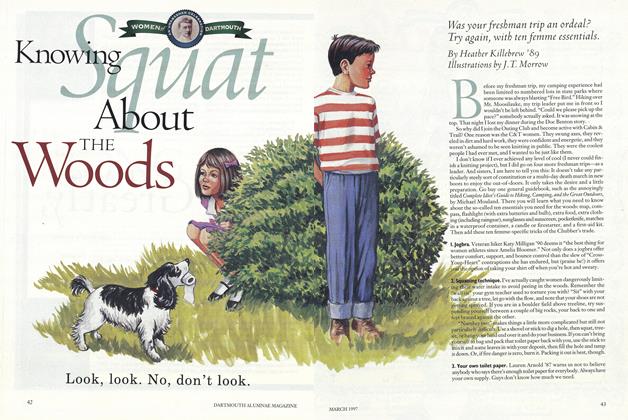

FeatureKnowing Squat About the Woods

MARCH 1997 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

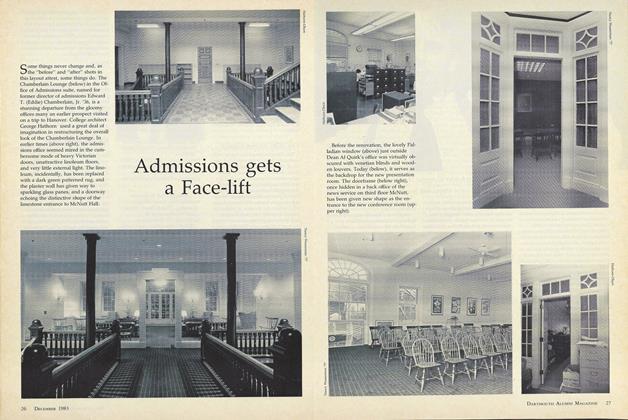

FeatureAdmissions gets a Face-lift

DECEMBER 1983 By Nancy Wasserman -

Feature

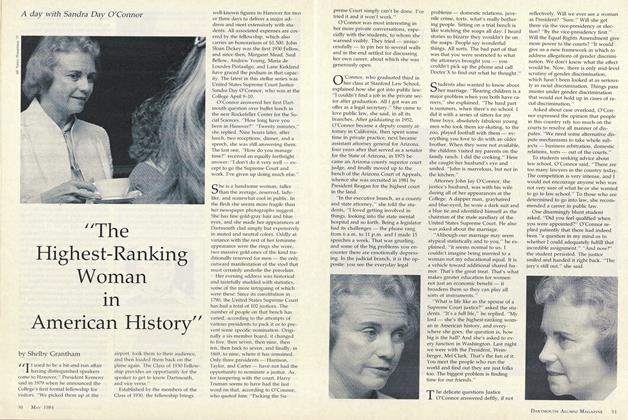

Feature"The Highest-Ranking Woman in American History"

MAY 1984 By Shelby Grantham