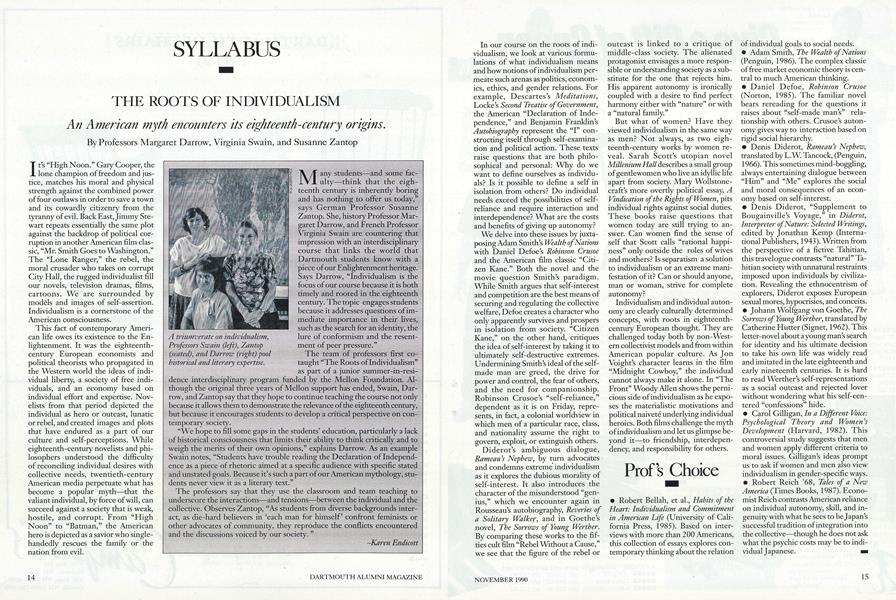

An American myth encounters its eighteenth-century origins.

Professors Margaret Darrow, Virginia Swain, and Susanne Zantop

It's "High Noon." Gary Cooper, the lone champion of freedom and justice, matches his moral and physical strength against the combined power of four outlaws in order to save a town and its cowardly citizenry from the tyranny of evil. Back East, Jimmy Stewart repeats essentially the same plot against the backdrop of political corruption in another American film classic, "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington." The "Lone Ranger," the rebel, the moral crusader who takes on corrupt City Hall, the rugged individualist fill our novels, television dramas, films, cartoons. We are surrounded by models and images of self-assertion. Individualism is a cornerstone of the American consciousness.

This fact of contemporary American life owes its existence to the Enlightenment. It was the eighteenth-century European economists and political theorists who propagated in the Western world the ideas of individual liberty, a society of free individuals, and an economy based on individual effort and expertise. Novelists from that period depicted the individual as hero or outcast, lunatic or rebel, and created images and plots that have endured as a part of our culture and self-perceptions. While eighteenth-century novelists and philosophers understood the difficulty of reconciling individual desires with collective needs, twentieth-century American media perpetuate what has become a popular myth that the valiant individual, by force of will, can succeed against a society that is weak, hostile, and corrupt. From "High Noon" to "Batman," the American hero is depicted as a savior who singlehandedly rescues the family or the nation from evil.

In our course on the roots of individualism, we look at various formulations of what individualism means and how notions of individualism permeate such arenas as politics, economics, ethics, and gender relations. For example, Descartes's Meditations, Locke's Second Treatise of Government, the American "Declaration of Independence," and Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography represent the"I" constructing itself through self-examination and political action. These texts raise questions that are both philosophical and personal: Why do we want to define ourselves as individuals? Is it possible to define a self in isolation from others? Do individual needs exceed the possibilities of self-reliance and require interaction and interdependence? What are the costs and benefits of giving up autonomy?

We delve into these issues by juxtaposing Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations with Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe and the American film classic "Citizen Kane." Both the novel and the movie question Smith's paradigm. While Smith argues that self-interest and competition are the best means of securing and regulating the collective welfare, Defoe creates a character who only apparently survives and prospers in isolation from society. "Citizen Kane," on the other hand, critiques the idea of self-interest by taking it to ultimately self-destructive extremes. Undermining Smith's ideal of the self-made man are greed, the drive for power and control, the fear of others, and the need for companionship. Robinson Crusoe's "self-reliance," dependent as it is on Friday, represents, in fact, a colonial worldview in which men of a particular race, class, and nationality assume the right to govern, exploit, or extinguish others.

Diderot's ambiguous dialogue, Rameau's Nephew, by turn advocates and condemns extreme' individualism as it explores the dubious morality of self-interest. It also introduces the character of the misunderstood "genius," which we encounter again in Rousseau's autobiography, Reveries ofa Solitary Walker, and in Goethe's novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther By comparing these works to the fifties cult film "Rebel Without a Cause," we see that the figure of the rebel or outcast is linked to a critique of middle-class society. The alienated protagonist envisages a more responsible or understanding society as a substitute for the one that rejects him. His apparent autonomy is ironically coupled with a desire to find perfect harmony either with "nature" or with a "natural family."

But what of women? Have they viewed individualism in the same way as men? Not always, as two eighteenth-century works by women reveal. Sarah Scott's Utopian novel Millenium Hall describes a small group of gentlewomen who live an idyllic life apart from society. Mary Wollstonecraft's more overtly political essay, AVindication of the Rights of Women, pits individual rights against social duties. These books raise questions that women today are still trying to answer. Can women find the sense of self that Scott calls "rational happiness" only outside the roles of wives and mothers? Is separatism a solution to individualism or an extreme manifestation of it? Can or should anyone, man or woman, strive for complete autonomy?

Individualism and individual autonomy are clearly culturally determined concepts, with roots in eighteenth-century European thought. They are challenged today both by non-Western collectivist models and from within American popular culture. As Jon Voight's character learns in the film "Midnight Cowboy," the individual cannot always make it alone. In "The Front" Woody Allen shows the pernicious side of individualism as he exposes the materialistic motivations and political naivete underlying individual heroics. Both films challenge the myth of individualism and let us glimpse beyond it to friendship, interdependence and responsibility for others.

A triumverate on individualism,Professors Swain (left), Zantop(seated), and Darrow (right) poolhistorical and literary expertise.

Many students and some faculty think that the eighteenth century is inherently boring and has nothing to offer us today," says German Professor Susanne Zantop. She, history Professor Margaret Darrow, and French Professor Virginia Swain are countering that impression with an interdisciplinary course that links the world that Dartmouth students know with a piece of our Enlightenment heritage. Says Darrow, "Individualism is the focus of our course because it is both timely and rooted in the eighteenth century. The topic engages students because it addresses questions of immediate importance in their lives, such as the search for an identity, the lure of conformism and the resentment of peer pressure." The team of professors first cotaught "The Roots of Individualism" as part of a junior summer-in-residence interdisciplinary program funded by the Mellon Foundation. Although the original three years of Mellon support has ended, Swain, Darrow, and Zantop say that they hope to continue teaching the course not only because it allows them to demonstrate the relevance of tie eighteenth century, but because it encourages students to develop a critical perspective on contemporary society. "We hope to fill some gaps in the students' education, particularly a lack of historical consciousness that limits their ability to think critically and to weigh the merits of their own opinions," explains Darrow. As an example Swain notes, "Students have trouble reading the Declaration of Independence as a piece of rhetoric aimed at a specific audience with specific stated and unstated goals. Because it's such a part of our American mythology, students never view it as a literary text." The professors say that they use the classroom and team teaching to underscore the interactions and tensions between the individual and the collective. Observes Zantop, "As students from diverse backgrounds interact, as die-hard believers in 'each man for himself' confront feminists or other advocates of community, they reproduce the conflicts encountered and the discussions voiced by our society. " Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureShrink Rap

November 1990 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

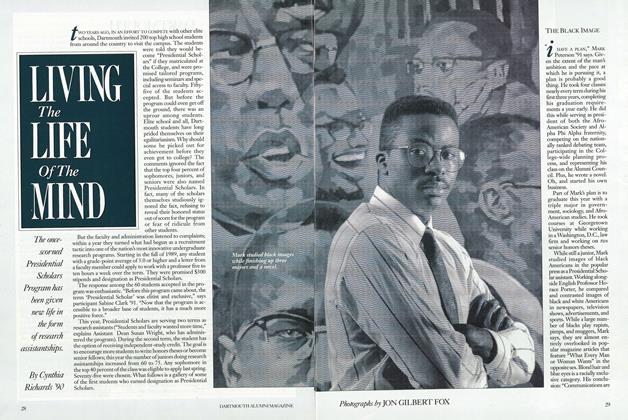

FeatureLIVING THE LIFE OF THE MIND

November 1990 By Cynthia Richards '90 -

Feature

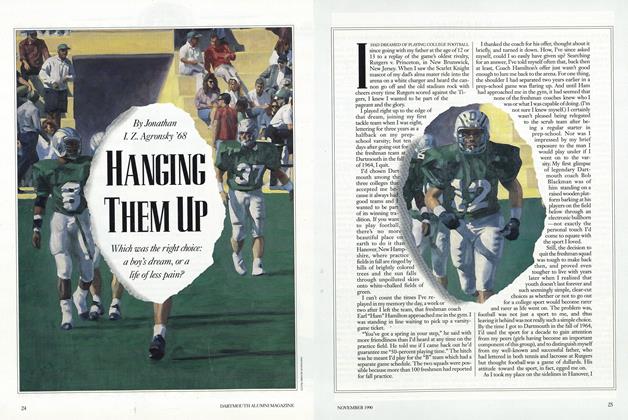

FeatureHanging Them Up

November 1990 By Jonathan I. Z. Agronsky '68 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHorace Fletcher 1870

November 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWalter F. Wanger 1915

November 1990 -

Cover Story

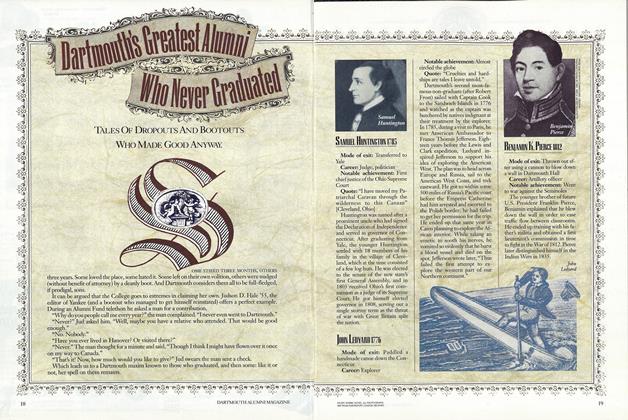

Cover StoryJohn Ledyard 1776

November 1990