"Ideas flash into theminds of scientists asunaccountably aslyrical phrases form inthe minds of poets."

MORE THAN THREE DECADES AGO, IN a celebrated lecture at Cambridge University, C.P. Snow argued that "the intellectual life of the whole of western society is increasingly being split into two polar groups": literary intellectuals and scientists. When a society's literary intellectuals cannot converse with its scientific intellectuals, so that each may gain an appreciation of the other's competencies and premises, then, as Snow wrote, "no society is going to be able to think with wisdom."

In the generation since Lord Snow described these "two cultures," the scientific revolution has changed our world at least as pervasively as the industrial revolution did the world of the nineteenth century. Science and technology have made the world considerably more exciting—and more dangerous. They influence the form and content of our culture so extensively that virtually every major decision we make—whether it be political, economic, social, or moral—must take account of their accomplishments.

Yet, as the achievements of scientific research have become more wondrous, our society has responded with priderather than understanding; with awe rather than edification. I find this acutely disturbing.

As remarkable as the achievements of science are, they are inherently neither good nor evil. They have both immense creative promise and, in William Blake's phrase, "dark Satanic" potentialities. They may tell us that certain results are possible or predictable, but they cannot tell us what is politically prudent or socially just or morally right. For the responses to such concerns—humane responses that can discern the boundary between scientific facts and the political, social, and moral implications of those facts—we must look to citizens and leaders who have been liberally educated.

This is why Dartmouth has placed a priority on melding the humanities and the sciences, offering students the opportunity to glimpse the far reaches of knowledge in a setting of liberal learning. As science becomes more complex, so must the College's facilities become more sophisticated. Last summer, ground was broken on a $28 million chemistry building, the first academic center to be constructed during my presidency. Launched with a $3.5 million gift from John Rosenwald' 52, T '53, the building will provide Dartmouth students and faculty with laboratories and classrooms of unmatched quality.

Facilities alone will not produce the results we seek, however. In endeavoring to empower students with an understanding of science, a liberal education must emphasize that science is one of the magnificent achievements of the human mind—an intellectual activity of the greatest rigor, subtlety, complexity, and beauty. Just as a poet seeks to express an understanding of the world by imposing an order upon words, just as a painter seeks to convey a vision of reality by imposing an order upon light and color and form, just as a historian seeks to record and explain the past by imposing an order upon developments and events—so a scientist seeks to explain the riddles of the natural world by invoking intellect and imagination to impose an order upon disparate facts and phenomena.

Still another important aspect of science lies in the aesthetic experience it provides—in the exhilaration of the chase, the satisfaction of penetrating the unknown, the framing of the decisive generalization. Far from being a dry or heartless exercise, science pulsates with intuition and imagination. Ideas flash into the minds of scientists as unaccountably as lyrical phrases form in the minds of poets. "The father of geology," novelist Samuel Butler wrote, "was he who, seeing fossil shells on a mountain, conceived the theory of the deluge."

Liberal learning still must bridge the "gulf of mutual incomprehension" between the two cultures that C.P. Snow warned against in 1959. It is for us today a challenge to educate students of the humanities and social sciences to understand the natural sciences and their processes, to appreciate the resourcefulness of the scientific imagination, and to think wisely about the social uses and moral limits of scientific and technological achievements.

It is a challenge, in short, to educate young men and women to be worthy of the responsibilities of democratic citizenship. Our task is to ensure that, during the course of their years here, Dartmouth will prepare its students well for meeting those responsibilities.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWHEN THE YOUNG TURKS CAME

December 1990 By John G. Kemeny -

Cover Story

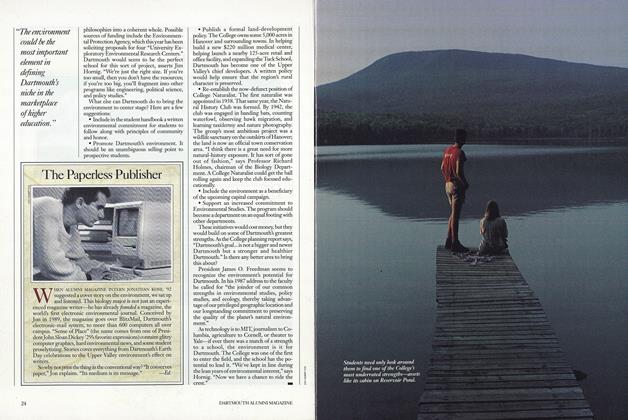

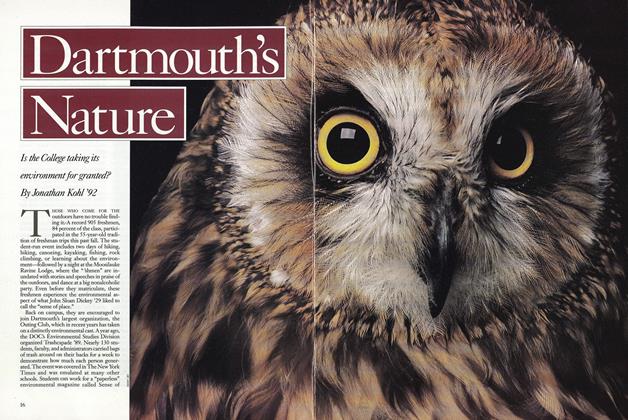

Cover StoryDartmouth’s Nature

December 1990 By Jonathan Kohl ’92 -

Feature

FeatureHENRY’S SPIEL

December 1990 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK’S JOURNAL

December 1990 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleThe Case Against the Dartmouth Review

December 1990 By George B. Munroe -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

December 1990 By Michael H. Carothers

James O. Freedman

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorPresents Accounted For

June 1994 -

Article

ArticleTHE SENSE OF PLACE

SEPTEMBER 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Postponed Power

May 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Lifelong Pursuit of Education

Winter 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTowering Silences

APRIL 1997 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleBack to the Future

JUNE 1998 By James O. Freedman