Commencement links the privilege of education to lives of broad vision.

We call this ceremony a commencement, but what it really marks is a transition from a period of years devoted to intensive learning and preparation to a period of years in which you will experience the excitement of testing the skills and applying the knowledge thatyou have acquired at Dartmouth

In the course of that transition, you will move beyond your formal years of liberal education and assume new responsibilities as graduate students or professionals, answerable to yourselves and to society for the quality of your performance as well as for the independence, humanity, and soundness of your judgment. What lies ahead, as you conclude your college career, is a landscape fruitful in possibility.

You have come of age in a nation that fails to provide higher education to innumerable students just as innately talented and just as earnestly ambitious as you are. Each of you has been the beneficiary of rare privilege. Each of you is a part of that fortunate fraction of American youth that has been afforded the opportunity to secure an exceptional education. From those to whom much has been given, much is properly expected.

The college years have been a time, in Robert Frost's words, to "build soil" a time to pursue a liberal education, to form your character, and to commit your lives to worthy goals. The years ahead will be a time to reap the harvest of the seeds that you have chosen to sow in that rich soil to accomplish those things that will bring you satisfaction and fulfillment and will help to deepen the moral quality of our society.

Almost three-quarters of a century ago, in his volume of philosophical lectures entitled Science and the Modern World, Alfred North Whitehead offered some memorable observations on the duties and dangers of professional life.

He pointed out that the rate at which the world was changing was accelerating ever more rapidly so much so, he predicted, that in the course of a lifetime a professional person would be called upon to face novel situations for which neither prior training nor previous experience could provide a parallel. Whitehead observed, "The fixed person for the fixed duties, who in older societies was such a godsend, in the future will be a public danger." He also noted that the expansion of professional knowledge had been accompanied by a contraction of general knowledge a contraction that produced "minds in a groove." As he put it, "Each profession makes progress, but it is progress in its own groove."

As a result, Whitehead feared the loss of a directive force in democratic society. "The leading intellects lack balance," he warned. "They see this set of circumstances, or that set; but not both sets together." The melancholy consequence, he declared, is that the "task of coordination is left to those who lack either the force or the character to succeed in some definite career."

All of you who are graduating today can do much to address the problem that Whitehead so accurately foreshadowed. By virtue of your schooling and your habits of mind, you can offer society the benefit of your focused knowledge, as well as a wider vision and a larger sense of purpose. You can be broad-gauged without being superficial, skeptical without being cynical, caring without being sentimental.

I am confident that a recognition of this responsibility will guide your actions and inspire your idealism throughout your lives. I am confident, too, that Dartmouth has educated you as men and women of enduring intellectual and moral breadth, not as "minds in a groove."

I wish each of you every happiness and success in the years ahead. May your affection for "Dartmouth undying" be with you always. Congratulations and good luck!

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

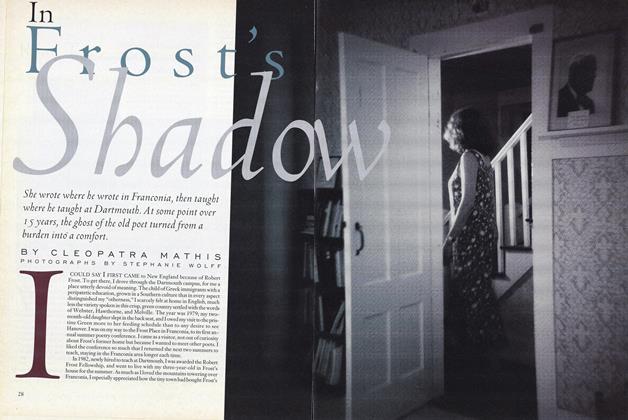

Cover StoryIn Frost's Shadow

September 1997 By CLEOPATRA MATHIS -

Feature

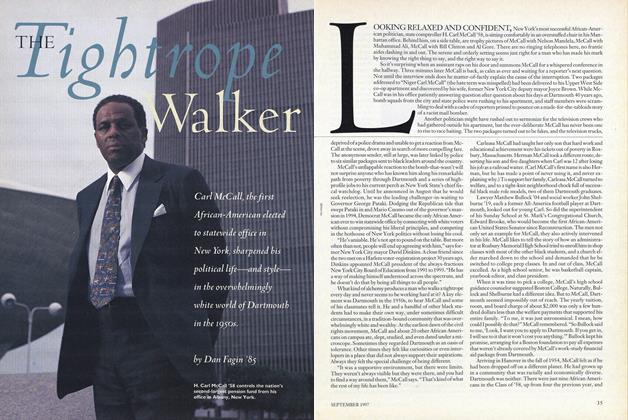

FeatureThe Tightrope

September 1997 By Dan Fagin '85 -

Feature

FeatureUninight

September 1997 By DOUGALD MACDONALD '82 -

Feature

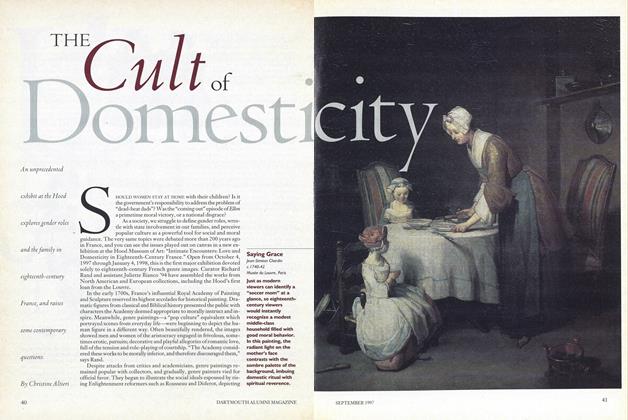

FeatureThe Cult of Domesticity

September 1997 By Christine Altieri -

Article

ArticleRoad Trip

September 1997 By Sarah Moore -

Article

ArticleElevator Going Up, AstroTurf Going Down

September 1997 By "E. Wheelock."

James O. Freedman

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorPresents Accounted For

June 1994 -

Article

ArticleMY HEROES

MARCH 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Human Scale

September 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleAdvancing the Human Condition

NOVEMBER 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Liberating Arts

MAY 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

FeatureAn Honor, To a Degree

Sept/Oct 2002 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN

Article

-

Article

ArticleMARRIAGE OF COACH O'CONNOR

December, 1908 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

April 1949 -

Article

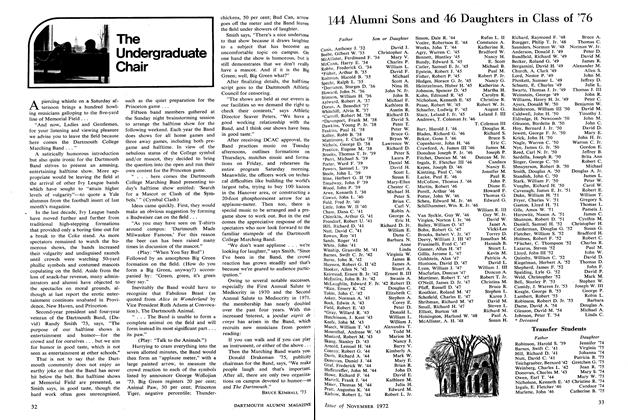

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

NOVEMBER 1972 By BRUCE KIMBALL '73 -

Article

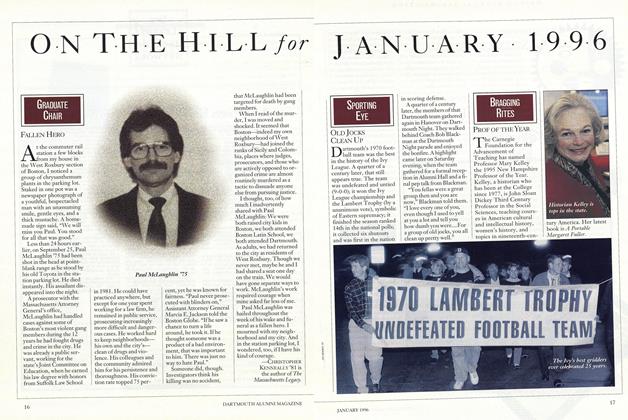

ArticleFallen Hero

January 1996 By Christopher -

Article

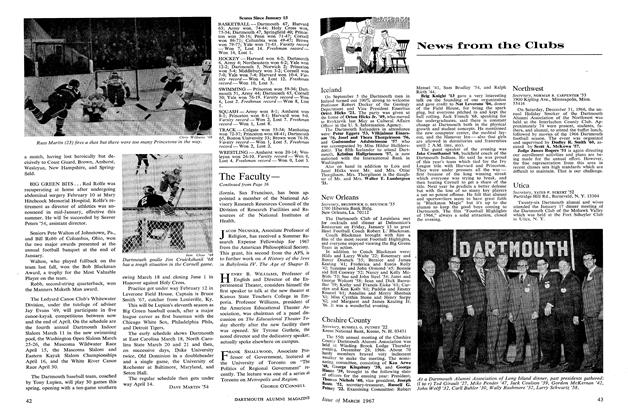

ArticleScores Since January 15

MARCH 1967 By DAVE MARTIN '54 -

Article

ArticleCrew Active

April 1948 By H. M. CUMMINGS '51