"It would be difficult for historians to determine precisely the reciprocal extent to which the law followed the social movement and the social movement followed the law."

WHEN I SPOKE AT the Commencement Exercises of the Vermont Law School last May, I talked about the importance of the lessons that the law has to teach the American polity, and the crucial role that lawyers must play in conveying those lessons to others. What follows is some of what I said.

The law does not exist in a vacuum. The fate of virtually every major political movement in American history—whether it be to abolish slavery, to establish suffrage for women, or to affirm equal opportunity for all citizens—has turned not only on the law but also on the social context in which it occurred.

For example, the drive to secure the rights of workers to organize and to bargain collectively originated in a political and social movement, but it could not have achieved its goals without the legitimating support of the law. By endorsing the creation of both a framework of employee rights (the Wagner Act) and a forum in which those rights could be vindicated (the NLRB), the law served as society's teacher.

Similarly, the law reinforced and validated the political and social goals of the civil rights movement by expressing, in the landmark judicial decisions and legislation of the 1950s and 1960s, the values of equality—particularly in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Without the symbolic validation and public authority that the law placed behind the civil rights movement, that movement's goals could not have been realized.

In both of these areas, as in so many others, it would be difficult for historians to determine precisely the reciprocal extent to which the law followed the social movement and the social movement followed the law. But it is certain that without the moral, social, and political pressure of the labor movement and the civil rights movement, the law would not have been changed. And had the law not been changed, the moral, social, and political force of both of these movements would have been diluted and perhaps frustrated.

When lawyers educate about the law's role in consolidating and legitimating social change, they are teaching about the pressures of context. It was Edmund Burke who wrote, "Circumstances (which with some gentlemen pass for nothing) give in reality to every political principle its distinguishing colour, and discriminating effect. The circumstances are what render every civil and political scheme beneficial or noxious to mankind."

It is important for Americans to understand, therefore, that in every major wave of historical change, the impact of political, social, and legal influences on the outcome is invariably mutual and reciprocal. Context matters. A new legislative act or judicial decision almost always represents an accommodation. It rarely gives any single contending force precisely what it wants, even if that force represents a decisive majority. In the pragmatic world of legislative and judicial decision-making, the more sharp-edged wishes of the majority are almost always compromised (as James Madison counseled they must be) by the pressures and complexity of context.

For me, then, one of the essential ways in which lawyers can effectively serve the public interest is by educating ordinary citizens in the uses and nature of the legal process. Certainly those citizens will hear all around them other voices, making more frightening claims for the nature of law—as the poet W. H. Auden understood so well:

Others say, Law is our Fate;Others say, Law is our State;Others say, others sayLaw is no moreLaw has gone away.And always the loud angry crowdVery angry and very loudLaw is We,and always the soft idiot softly Me.

I need not tell you that the law of the "loud angry crowd"—the law of the mob and of the "soft idiot"—is finally the result of a dark descent into accepting simple, nihilistic responses to the complicated, nuanced challenges of participatory democracy.

The best lawyers think of themselves not only as careful and caring practitioners of the law but also as educators of ordinary citizens. In their lives as lawyers they demonstrate the lessons that the law teaches: the lessons of democratic responsibility, the limitations of expertise, and the complexity of context. For in these lessons lie keys to the achievement of the public interest.

I take heart in the prospect that by emphasizing the lessons that the law has to teach, all of us can serve the public interest by strengthening public education in the nature of the democratic process.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

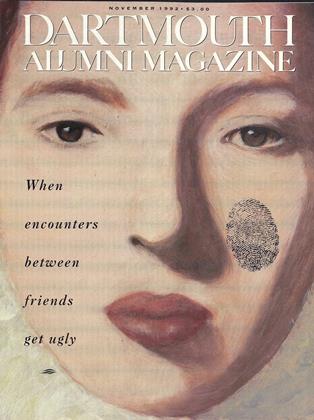

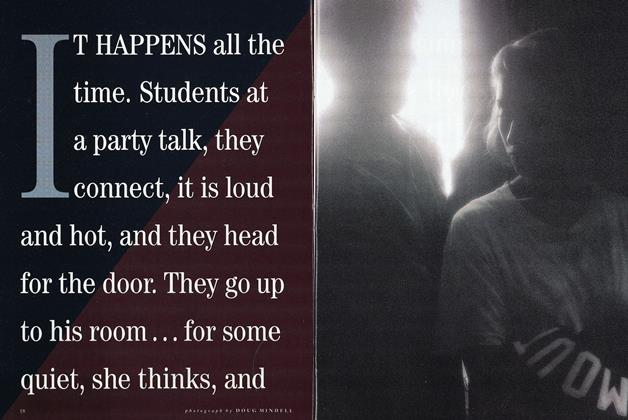

Cover Story

Cover StoryThen lings get ugly

November 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

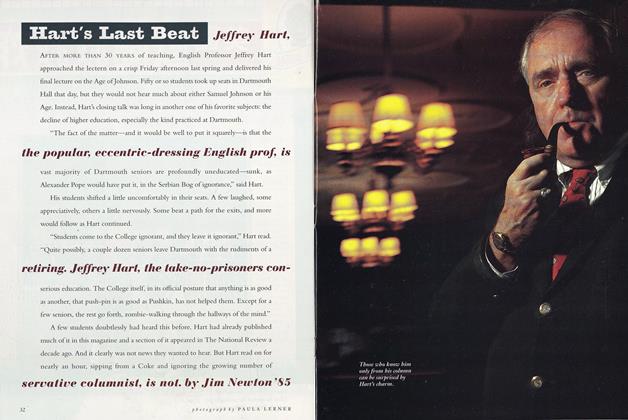

FeatureHart’s Last Beat

November 1992 By Jim Newton ’85 -

Feature

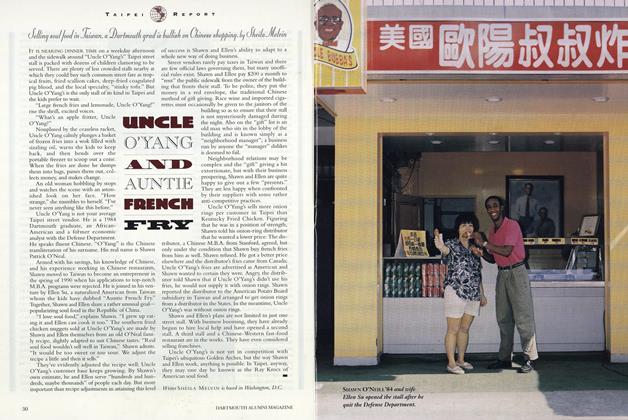

FeatureTaipei Report

November 1992 -

Article

ArticleIs Socialism Really Dead?

November 1992 By William L. Baldwin -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1992 By “E. Wheelock” -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

November 1992 By Mark Stern

James O. Freedman

-

Article

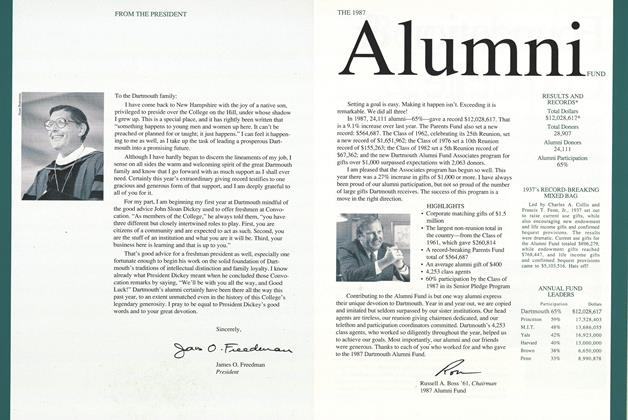

ArticleFROM THE PRESIDENT

OCTOBER • 1987 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTHE PASSIONS OF SCIENCE

December 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

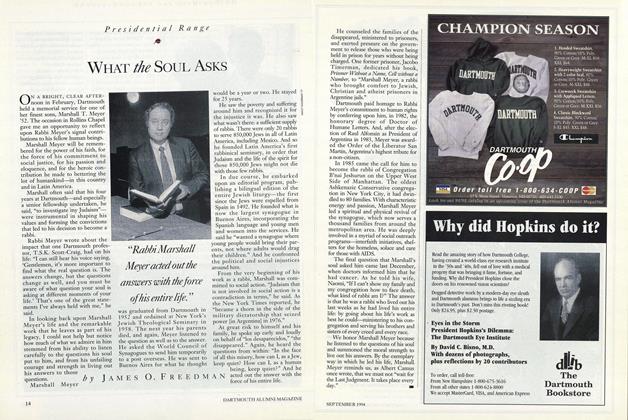

ArticleWhat the Soul Asks

SEPTEMBER 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticlePreparing for Contingencies

December 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Education Gap

January 1996 By James O. Freedman