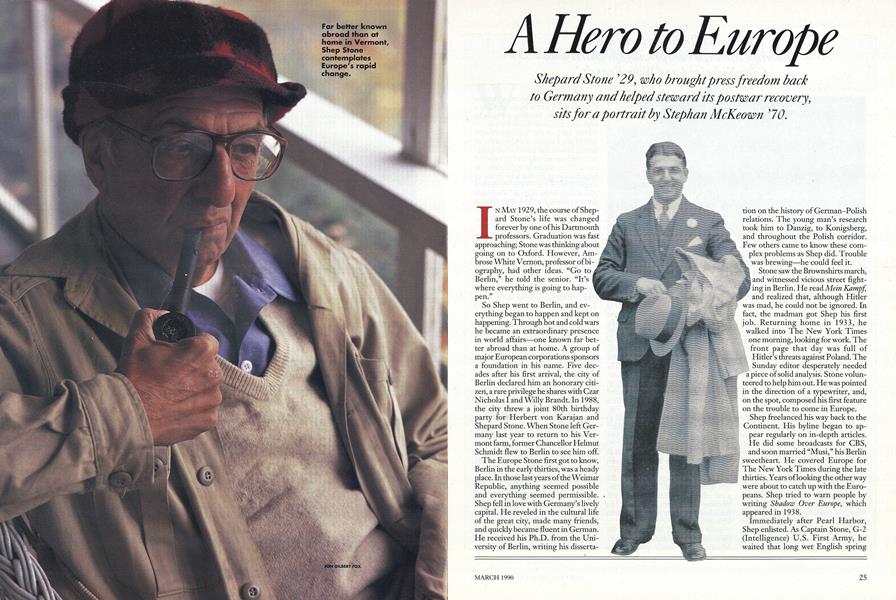

Shepard Stone '29, who brought press freedom back to Germany and helped steward its postwar recovery, sits for a portrait by Stephan McKeown '70.

IN MAY 1929, the course of Shepard Stone's life was changed forever by one of his Dartmouth professors. Graduation was fast approaching; Stone was thinking about going on to Oxford. However, Ambrose White Vernon, professor of biography, had other ideas. "Go to Berlin," he told the senior. "It's where everything is going to happen."

So Shep went to Berlin, and everything began to happen and kept on happening. Through hot and cold wars he became an extraordinary presence in world affairs one known far better abroad than at home. A group of major European corporations sponsors a foundation in his name. Five decades after his first arrival, the city of Berlin declared him an honorary citizen, a rare privilege he shares with Czar Nicholas I and Willy Brandt. In 1988, the city threw a joint 80th birthday party for Herbert von Karajan and Shepard Stone. When Stone left Germany last year to return to his Vermont farm, former Chancellor Helmut Schmidt flew to Berlin to see him off.

The Europe Stone first got to know, Berlin in the early thirties, was a heady place. In those last years of the Weimar Republic, anything seemed possible and everything seemed permissible. Shep fell in love with Germany's lively capital. He reveled in the cultural life of the great city, made many friends, and quickly became fluent in German. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Berlin, writing his dissertation on the history of German-Polish relations. The young man's research took him to Danzig, to Konigsberg, and throughout the Polish corridor. Few others came to know these complex problems as Shep did. Trouble Ik was brewing he could feel it.

Stone saw the Brownshirts march, and witnessed vicious street fighting in Berlin. He read Mem Kampf and realized that, although Hitler was mad, he could not be ignored. In fact, the madman got Shep his first job. Returning home in 1933, he walked into The New York Times one morning, looking for work. The front page that day was full of Hitler's threats against Poland. The Sunday editor desperately needed a piece of solid analysis. Stone volunteered to help him out. He was pointed in the direction of a typewriter, and, on the spot, composed his first feature on the trouble to come in Europe.

Shep freelanced his way back to the Continent. His byline began to appear regularly on in-depth articles.

He did some broadcasts for CBS, and soon married "Musi," his Berlin sweetheart. He covered Europe for The New York Times during the late thirties. Years of looking the other way were about to catch up with the Europeans. Shep tried to warn people by writing Shadow Over Europe, which appeared in 1938.

Immediately after Pearl Harbor, Shep enlisted. As Captain Stone, G-2 (Intelligence) U.S. First Army, he waited that long wet English spring that millions waited, for the greatest seaborne invasion in history. Shep landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day. Beginning at once to interrogate prisoners, he stayed close to the fighting all the way across France and Germany. Shepard Stone was one of the first, on an early spring day in 1945, to stare the barbarity of Buchenwald in the face. He saw the shuffling scarecrows, once human, only their eyes alive. Later, he took part in the American link-up with the Russians near Torgau. Even as he shook the comrades' hands, he thought of Europe's future. Could totalitarianism be avoided again? Now, as in the past, Europe would stand or fall depending on what happened in Germany.

Promoted to lieutenant colonel, Stone returned to Berlin as part of the Allied military government. The city he had loved no longer existed two years of thousand-bomber raids followed by the final Russian offensive had left Berlin a cratered moonscape, inhabited by starving wraiths. People needed coal, food, and shelter. After 12 years of totalitarian rule, they also needed re-education in democracy. Shep's special responsibility was the creation of an independent, democratic German press. He weeded out former Nazis, set journalistic standards, encouraged editors, and sent correspondents to the States to learn firsthand there about freedom of the press.

Returning to civilian life, the former reporter became assistant Sunday editor of The New York Times. One hectic Friday in 1949 his editor was away and Shep was trying to put the paper to bed. The phone rang. John J. McCloy, former assistant secretary of war and president of the World Bank, was asking for him. Shep had never met him, but he knew that McCloy had just been named U.S. high commissioner for Germany. McCloy, never having visited Germany, needed background. With no introduction, a voice of gravel and ice barked out, "Stone, I hear you are supposed to know something about Germany." Shep replied, "Well, Mr. McCloy, I've been there."

The Sunday deadline notwithstanding, McCloy came to lunch, ate a dozen oysters, and pumped him about Germany for hours. Shep was left with the bill. Months passed. Then, suddenly, a call came from Germany: Stone was to come over at once, to consult. His leave from the paper had already been arranged.

Shep went back to Germany for three months and stayed three years. Marshall Plan funds poured into the country. Shep became famous throughout Germany as McCloy's right-hand man, handling any task the high commissioner threw his way.

One assignment involved Shep's second alma mater, the University of Berlin, now in the Soviet zone. Impatient with censorship and an imposed curriculum, students spontaneously began moving books and desks to empty lots in the West. Professors joined them in the open air. The world press picked up on the story. Henry Ford II and Paul Hoffman of the Ford Foundation wanted a look. They were coming over.

On a bitterly cold day, Shep took charge of the visiting dignitaries. They were greeted by his friend Mayor Reuter, met students and faculty, and attended a lively debate on democracy held in an unheated Nissen hut. Ford and Hoffman were impressed. They asked what they could do to help. Citing a need for buildings, books, and staff, Shep coolly quoted a figure in the millions of marks. They approved on the spot, and the Free University of Berlin became a reality.

McCloy's right-hand man had made a lasting impression on Ford and Hoffman. By 1953, his work in Germany was complete. The Ford Foundation appointed Stone director for international affairs.

For the next 14 years, he initiated and supported countless programs to promote education, cultural exchange, and mutual understanding around the globe. At home, the Foreign Policy Association and the Council on Foreign Relations were funded to expand American knowledge of world affairs. Abroad, Hungarian refugees were provided with scholarships to study in Paris. In Berlin, the Literary Colloquium, the International Music Institute, and, later, the John F. Kennedy Institute, were all established with Foundation funds.

One day in 1959, Shep and his associates were kicking around an idea: wasn't it time to start talking to the Russians? "You either talk or you fight," they agreed. Stone had the hinds for a conference, but where to hold it was the question after all, the era of Joe McCarthy was barely over. On a hunch, Shep called his classmate, John Sloan Dickey '29. The president of Dartmouth was keen on Great Issues and enthusiastically agreed to hold the first postwar U.S.-Soviet meeting in Hanover. Faculty, students, townsfolk, and even the beautiful fall weather cooperated to welcome and impress the wary Soviet visitors. Encouraged, the Ford Foundation supported a series of conferences commemorating this successful first effort. Today, the Dartmouth Conferences continue in various locations around the world.

overseas. Berlin was an ideal location: what better place to discuss the split between East and West than the city where the two systems touched? He flew off to find Mayor Reuter. Meeting over coffee in Zurich's airport, the two men took 45 minutes to hammer out the details of the Aspen Institute, Berlin, Shepard Stone, director. After the Ford Foundation, Shepard Stone served for seven years as president of the International Association for Cultural Freedom in Paris. He was on the boards of many organizations, including the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies (now headed by former Dartmouth President David McLaughlin '54), At one Aspen conference, Shep followed up a suggestion that the institute found branches

quickly began to gain an international reputation. From 1974 to 1988, Shep hosted nearly 300 conferences, with more than 6,500 participants. His limitless contacts, vast experience, and sharp-witted ability to keep the pompous in line brought many of the world's brightest people from East and West together for no-nonsense discussions of such subjects as pollution, Poland, the future of Germany, and European anti-Americanism. Even the Russians participated.

Shepard Stone has now come home at last, but he has not retired. His friend, West German President Richard von Weizaeker, paid a visit to the Stone farm in Vermont last summer. Derek Bok, president of Harvard, has appointed him honorary chairman of the Department of European Affairs at the Kennedy School in Cambridge. A visiting professorship at the Free University of Berlin has been named in his honor; he will return annually to lecture in his beloved adopted city. The city's official guest house awaits him whenever he chooses to return. Back in South Newfane, Vermont, the barn bulges with files dating back to the 19205, waiting to be fashioned into an autobiography. Shep continues to apply sound judgment, deep knowledge, cultural tolerance, and a generous supply of good humor to the problems caused by ignorance and fear around the world. He is as busy as ever; so much remains to be done.

Far better known abroad than at home in Vermont, Shep Stone contemplates Europe's rapid change.

Captain Stone passes bombed-out ruinsin 1944. He was to return to Germanyto help administer the Marshall Plan.

Shep chats with his friend HenryKissinger and the mayor of West Berlin.

Stephan McKeown '70 spends much ofhis time as a portrait artist, paintingpeople who "interest" him. "I readabout Shepard Stonein The New YorkTimes," he says."When I found outhe was a Dartmouthgrad I couldn'T helpbut do his portraitin prose as well aspaint."

"The city of Berlin declared him an honorary citizen, a rare privilege he shares with Czar Nicholas I and Willy Brandt."

"The president of Dartmouth was keen on Great Issues, and enthusiastically agreed to hold the first postwar U.S Soviet meeting in Hanover."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth's Steady Course

March 1990 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureADDICTED TO CONVERSATION

March 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Feature

FeatureANCIENT PAGE TURNERS

March 1990 By JONI COLE AND LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeatureThe Purpose Gap

March 1990 -

Feature

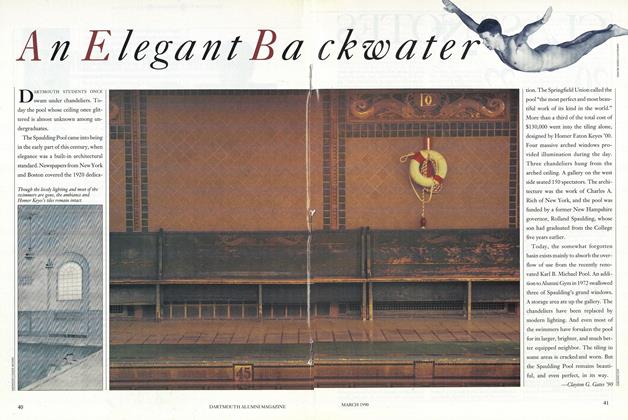

FeatureAn Elegant Backwater

March 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

March 1990

Features

-

Feature

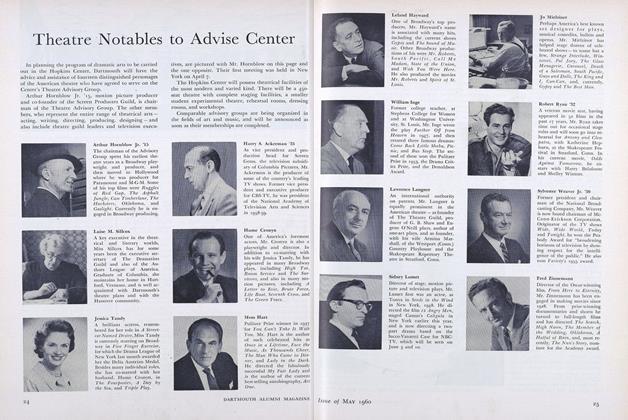

FeatureTheatre Notables to Advise Center

May 1960 -

Feature

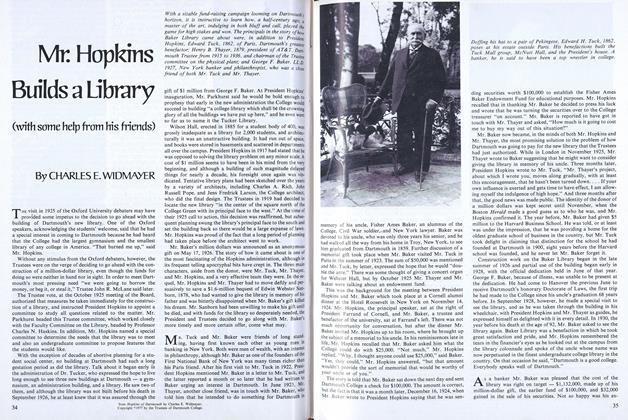

FeatureMr. Hopkins Builds a Library

April 1977 By CHARLES E. WIDMAyER -

Feature

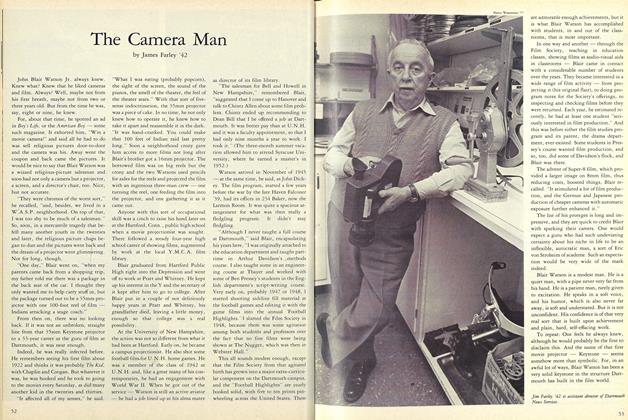

FeatureThe Camera Man

November 1982 By James Farley '42 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1957

July 1957 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureChartres in a Chevrolet

December 1974 By ROBERT L. McGRATH -

Feature

FeatureSEEKING TO BE WHOLE

MAY | JUNE 2014 By Shannon Joyce Prince ’09