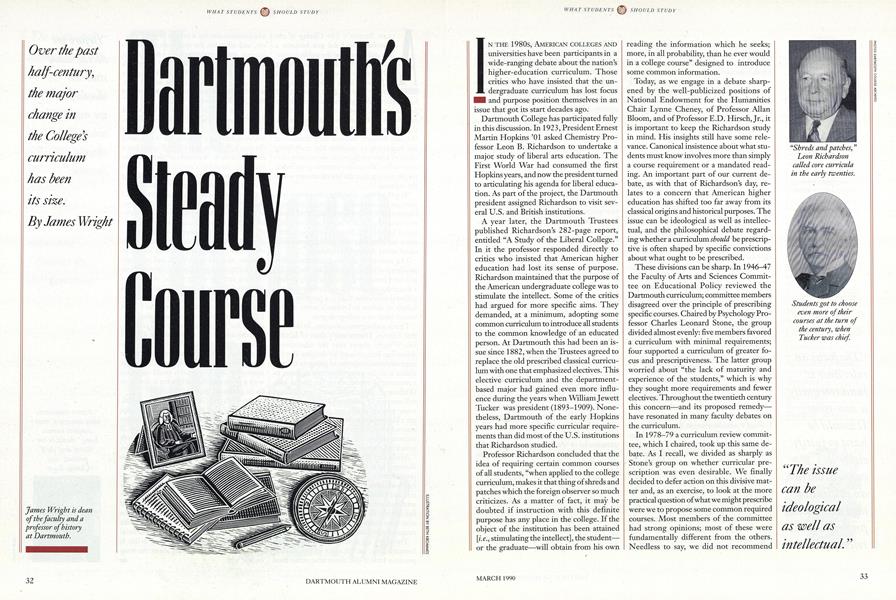

Over the past half-century, the major change in the College's curriculum has been its size.

IN THE 1980s, AMERICAN COLLEGES AND universities have been participants in a wide-ranging debate about the nation's higher-education curriculum. Those critics who have insisted that the undergraduate curriculum has lost focus and purpose position themselves in an issue that got its start decades ago.

Dartmouth College has participated fully in this discussion. In 1923, President Ernest Martin Hopkins '01 asked Chemistry Professor Leon B. Richardson to undertake a major study of liberal arts education. The First World War had consumed the first Hopkins years, and now the president turned to articulating his agenda for liberal education. As part of the project, the Dartmouth president assigned Richardson to visit several U.S. and British institutions.

A year later, the Dartmouth Trustees published Richardson's 282-page report, entitled "A Study of the Liberal College." In it the professor responded directly to critics who insisted that American higher education had lost its sense of purpose. Richardson maintained that the purpose of the American undergraduate college was to stimulate the intellect. Some of the critics had argued for more specific aims. They demanded, at a minimum, adopting some common curriculum to introduce all students to the common knowledge of an educated person. At Dartmouth this had been an issue since 1882, when the Trustees agreed to replace the old prescribed classical curriculum with one that emphasized electives. This elective curriculum and the departmentbased major had gained even more influence during the years when William Jewett Tucker was president (1893-1909). Nonetheless, Dartmouth of the early Hopkins years had more specific curricular requirements than did most of the U.S. institutions that Richardson studied.

Professor Richardson concluded that the idea of requiring certain common courses of all students, "when applied to the college curriculum, makes it that thing of shreds and patches which the foreign observer so much criticizes. As a matter of fact, it may be doubted if instruction with this definite purpose has any place in the college. If the object of the institution has been attained [i.e., stimulating the intellect], the student or the graduate will obtain from his own reading the information which he seeks; more, in all probability, than he ever would in a college course" designed to introduce some common information.

Today, as we engage in a debate sharpened by the well-publicized positions of National Endowment for the Humanities Chair Lynne Cheney, of Professor Allan Bloom, and of Professor E.D. Hirsch, Jr., it is important to keep the Richardson study in mind. His insights still have some relevance. Canonical insistence about what students must know involves more than simply a course requirement or a mandated reading. An important part of our current debate, as with that of Richardson's day, relates to a concern that American higher education has shifted too far away from its classical origins and historical purposes. The issue can be ideological as well as intellectual, and the philosophical debate regarding whether a curriculum should be prescriptive is often shaped by specific convictions about what ought to be prescribed.

These divisions can be sharp. In 1946-47 the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Committee on Educational Policy reviewed the Dartmouth curriculum; committee members disagreed over the principle of prescribing specific courses. Chaired by Psychology Professor Charles Leonard Stone, the group divided almost evenly: five members favored a curriculum with minimal requirements; four supported a curriculum of greater focus and prescriptiveness. The latter group worried about "the lack of maturity and experience of the students," which is why they sought more requirements and fewer electives. Throughout the twentieth century this concern and its proposed remedy have resonated in many faculty debates on the curriculum.

In 1978-79 a curriculum review committee, which I chaired, took up this same debate. As I recall, we divided as sharply as Stone's group on whether curricular prescription was even desirable. We finally decided to defer action on this divisive matter and, as an exercise, to look at the more practical question of what we might prescribe were we to propose some common required courses. Most members of the committee had strong opinions; most of these were fundamentally different from the others. Needless to say, we did not recommend specific curricular requirements!

Independent of specific recommendations, periodic curricular reviews are as important for the discussions they generate as for any substantive curricular revisions that may result. Recognizing this, in the summer of 1989, as part of the self study that relates to our current planning deliberations, the Arts and Sciences Planning Committee recommended an evaluation and review of the arts and sciences curriculum at Dartmouth.

It is important to keep this current review in perspective: it is but part of the continuing discussion (and occasional revision) of the curriculum that Dartmouth has undertaken during the last century. It is also timely to suggest that there are some misunderstandings over the current state of our curriculum. Two are particularly significant: first, the idea that the Dartmouth degree requirements have recently become softer, less focused, and less directed; second, the belief that the curriculum has become a captive of "relevance" that it relates to current interests and has less of an intellectual anchor than in the past. Implicit in each of these arguments is the assumption that in some recent time, some remembered past, standards were standards and they related to timeless principles. For the purpose of considering these issues, I have attempted to compare the current state of the Dartmouth curriculum with that of a half century ago.

The academic year 1939-40 provides a useful point of comparison. Ernest Martin Hopkins was in his 24th year as Dartmouth president and had firmly put his imprint upon the College. It was only in retrospect, only with the passage of time, that we would recognize what an important transition the College was undergoing in this, the first year of World War II. Students worried about their economic future as the nation continued to stagger through the Great Depression; now they had new issues as well, issues having to do with national security. Dartmouth students heatedly debated the relative merits of isolation and activism. The rapid fall of France and the hasty evacuation of Dunkirk in the late spring of 1940 underlined the likelihood that this debate would have more than an academic role in their lives.

The degree requirements in the fall of 1939 were one year of foreign language (or two years for the uncommon student who had no high school language preparation), two semesters of English, four social-sciences courses from a restricted list, four semesters in two different science departments, two years of physical education (including a hygiene course in the freshman year), and completion of a major.

The common experience for this generation of Dartmouth students was English 1-2, a freshman literature and composition sequence, and Social Sciences 1-2 introductory freshman courses. Students could have these social-science courses waived if they successfully passed a placement examination in European and American history. They still had to select four social-science courses from a list of introductory offerings. Social Sciences 1-2 aimed at creating "a lively interest in contemporary social, economic, and political problems, and the capacity to approach such problems from a critical yet tolerant point of view," according to the catalog. They emphasized the importance of facts and sequence and stressed interrelationships among the social sciences. The focus was on Europe and the United States. With Professor John Gazley in charge, the courses clearly had a historical emphasis.

It is important to note that this social-science sequence had only been required since 1936. Earlier, the requirement was a onesemester course on "Evolution" and another on "Industrial Society." The latter had in turn replaced a "Citizenship" course requirement. These, along with the Hygiene course, had been required since the end of World War I and reflected the shared concern of the faculty and President Hopkins that Dartmouth students be introduced to these important emerging issues. The Hopkins curriculum following the pattern commenced in the Tucker years early in the century—emphasized (and required) courses aimed at social development, even practicality, rather than common classical knowledge. President Hopkins and the faculty had discontinued the last of the classical language and literature requirements following the Richardson report.

The curriculum continued to evolve after World War II during the presidency of John Sloan Dickey. An important innovation of this era was the "Great Issues" course required of all seniors. The faculty also expanded the pool of courses from which students could meet their social-science and science requirements. The faculty committee that recommended these changes declined to challenge the Richardson-Hopkins tradition; its report argued that "our job in the liberal arts college is not to teach a student what he is to know, but to extend his intellectual horizon and increase his capacity for learning throughout life, in endeavors and fields that we cannot now even guess at."

The Great Issues requirement lasted until 1966. It was, by all recollections, a memorable part of the curriculum in the post-war years. Other modifications marked the Dickey era, including additional expansion of the pool from which social-science and science distributive courses could be elected. Starting with the class of 1950, a requirement for courses in the humanities accompanied this expansion. The Hopkins-era curriculum, beginning with the Richardson report, had not required humanities courses beyond those of English Composition and a foreign language. The Hygiene requirement was abolished in the late 19505. The last reform of the Dickey period was the freshman seminar, a broadly based composition course. The faculty developed it on an experimental basis in 1965 and approved it permanently in 1969. This replaced the second course in the English composition requirement.

These revisions basically set the degree requirements currently in place. Dartmouth resisted the national pattern of significantly reducing these requirements during the 1960s. The degree requirements of 1989-90 would be familiar to Dartmouth graduates of the mid-1960s. Indeed, they would be familiar to earlier students as well. (There is some difficulty in comparing courses before 1958 with those after that year because of the change to the three-term calendar. Older, two-semester courses that were year-long sequences are now two-term courses that are presumably equivalent but require two-thirds of a year. Put differently, students now normally take three courses a term for a total of nine a year; in the old semester calendar they typically took five courses a semester for a total of ten a year.)

With the calendar change in mind, let us review the current degree requirements. Freshmen who matriculated in the fall of 1989 must take an English composition course and a freshman seminar; they must complete the equivalent of three courses in a foreign language; as part of their distribution requirement they must take four courses in the Humanities, four in the Sciences, and four in the Social Sciences; they must complete a one-year physical education requirement; and they must complete a major. In addition, beginning with the class of 1985, all students have been required to complete as one of their 35 courses one that "takes as its subject the study of a culture or cultures other than those of Europe or the Euro-pean-based cultures of the United States or Canada." Currently, 115 such courses satisfy this "non-western" requirement.

Besides the non-western addition, the basic differences between the degree requirements of 1939-40 and those of 1989-90 have to do with defining "distributive" requirements. The other requirements such as foreign language and English composition are fundamentally the same, as are those for physical education (except for the dropping of the Hygiene requirement). The requirement for a major constitutes a separate category; discussion of this would necessitate a department-by-department comparison.

A few generalizations regarding changes in the major are possible. Most departments now offer a much broader program and tend to require more courses for completion of the major than they did in 1939-40. Since the 1960s, graduating students have not had to complete comprehensive examinations in their major. Ironically, expanding subject matter to make departments more comprehensive intellectually makes a comprehensive examination less practicable. Effective comprehensive examinations need to have an understood focus and a commonly accepted rigor. Departments need to be prepared to tell students in the week before graduation that they will not graduate despite having successfully completed all of the necessary courses. Memories to the contrary notwithstanding, this has seldom been the case. One of the principles which guided department-examination procedures in 1939-40 illustrates the difficulty of making such a process rigorous and meaningful: "It shall not be a test the passing of which is unduly difficult of attainment by men of the lower intellectual level among the undergraduate body, who have honestly attempted the work of synthesizing the material of the Major subject."

Apart from the changes in the major, the most significant difference since 1940 has been in the distributive requirement. Distribution a half-century ago was based on a more hierarchical view of knowledge that insisted upon prerequisites in nearly all fields. Students met the social-science requirement by taking the mandatory Social Science 1-2 courses and then by selecting two other introductory courses in Economics, Sociology, or Political Science, or by electing the Social Science 3-4 courses in the sophomore year. These latter were interdepartmental courses that sought to describe "a few of the more important contemporary institutions and problems of the United States," according to the catalog. Topics discussed in 1939-40 included money and banking, race, family, consumers, and international relations.

Today's Dartmouth students have no prescribed manner of meeting their distribution requirement. Essentially, any four courses in the Humanities, Sciences, and Social Sciences will do. The earlier requirements assumed that introductory courses were appropriate to meet this obligation.

On the other hand, current students do have a broader requirement. They must take four courses in the Humanities; students 50 years ago were not obligated to take any Humanities courses beyond those in English and foreign language.

Students in 1939-40 did not have a common intellectual experience except for English composition. Current students cannot even claim this; freshmen who demonstrate proficiency in composition are exempt from the requirement and enroll immediately in a freshman seminar. Approximately 37 percent of the class of 1993 earned test scores high enough to have the English requirement waived. In 1939-40 there apparently was no exemption provided for English composition. The College did permit exemption from Social Science 1-2, and 40 of 643 freshmen entering in the fall of 1939 received this. All other Social Science and Science requirements allowed choices, so that it was not possible to assume common learning at Dartmouth. With the exception of English composition and Hygiene, the only course commonly required of all Dartmouth students at any time during the last half-century was the Great Issues course, which lasted about 20 years. Given that the real strength of Great Issues was its relevance to contemporary matters, it varied from year to year so the shared experience was within each senior class.

Providing resources for foundation courses is not a trivial problem if one assumes 1,050 students sharing a course that meets Dartmouth's standards of quality. The current Freshman Seminar requirement is a good example. All freshmen must take a seminar in which no more than 16 of them read in a topic and write several papers. Teaching this involves an investment of the equivalent of more than 15 full-time members of the faculty more than five percent of our total instructional effort. Now, surely, not all required courses need be so labor-inten-sive but at Dartmouth they have tended to be. We need to be very clear about what we seek to accomplish if we make a commitment of this magnitude. And then we must be clear that we can sustain the effort for a reasonable time. Schools in which graduate students assume an important instructional role find such courses easier to manage.

When History Professor Louis Morton and a faculty committee recommended discontinuing Great Issues in 1966, they summarized the problem of required courses: "the student resentment against required attendance, the difficulty of managing a program that involves some 650 students of different backgrounds, interests, and concerns, and the difficulty of maintaining a consistently high quality of presentation by outside lecturers week after week throughout the year." Morton's study noted that these problems had been part of "Great Issues" ever "since its inception." In addition, "recent changes in the College, changes in the student body, in the curriculum, and in the faculty" made continuation of "Great Issues" problematical. None of which denies its importance and success for a generation. No required large-section course in the twentieth century lasted as long.

For those who think that the Morton Committee's concern about required courses is a response peculiar to the 1960s, it is useful to consider Richardson's report again. He wrote in 1924 that "the more compulsion we exercise upon the individual in the choice of the subject matter which he is to study, the less effective are the results."

It is impossible to describe briefly the specifics of curricular expansion over the last half century. We have entire new areas of inquiry—computer science, nuclear physics, cell biology, gender studies, digital electronics, postmodernism, and, indeed, the history and literature of the last 50 years. We have added departments, such as Drama and Film Studies and Visual Studies, that reflect some traditional Dartmouth interests; and we have some new Dartmouth strengths with the opening of Hopkins Center and the Hood Museum. We have sharpened and expanded our international curriculum, a process that John Dickey inaugurated in his first address as president. We now teach 12 foreign languages (including classical Greek and Latin four more than in 1939), and we offer off-campus programs at some 44 sites. Nearly two-thirds of the class of 1993 will elect to study off campus with a member of the Dartmouth faculty.

It is not the case, however, that all has been expansion, that no curricular area or course has been discontinued. Dartmouth no longer has departments such as Administration, Biography, Biblical History and Literature, Graphics, and Engineering, as it did in 1939. The curriculum no longer includes such courses as "Men of Modern Britain," "Economic Botany," "Proposed Plans for Economic Reform," "Problems in High School Administration," "Highway Engineering," "The Mathematics of Insurance," "Present Day Philosophy," "Radio Instruments and Measurements," and "The Modern City and its Problems."

Dartmouth's faculty share with our counterparts at other colleges and universities a commitment to create, expand, and teach on the frontiers of knowledge. This is not a zero-sum game. New courses in molecular genetics do not replace courses in plant pathology; new courses that include the writings of Norman Mailer or Toni Morrison do not replace older courses that focus on the writings of Emily Dickinson or Charles Dickens; new courses on post-war Japanese history do not replace traditional offerings in Medieval history. Needless to say, it would have been very difficult to impose a non-western curricular requirement in 1939; only about a dozen courses in that curriculum would have qualified for this, as compared to the current 115.

organized around continuing administrative structures that span departments and disciplines. An important part of the contemporary curriculum, they include Asian Studies, African and African-American Studies, Women Studies, Environmental Studies, Comparative Literature, Native American Studies, Mathematics and Social Sciences, Linguistics and Cognitive Science, as well as a program recently approved by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences in Latin American and Caribbean Studies. It is these Academic Programs that are usually the object of the "relevance" criticism. Non-western and nonclassical areas are particular targets of concern. This focus on "relevance" is fundamentally a non-issue, even a foolish proposition. It would be hard to justify either a curriculum or an institution that was not "relevant."

Much of the support for a classical core curriculum seems to stem from a conviction that there are traditional fields of study that are profoundly relevant and that have a role in shaping values and ideas and discipline that will help us to live better lives. Relating courses to current issues has been an important part of the Dartmouth curriculum since the end of the First World War from Hopkins's course on Citizenship to Dickey's Great Issues. The 1939—40 analogue to some of our Academic Programs was the "Topical Major" in such subjects as "National Problems Social and Economic." National and international problems continue to have a curricular place. Surely no one would argue that matters of, say, race and gender are any less timely, topical, and fundamentally important in our current curriculum. And they bring real academic and intellectual strength as well as relevance to our course of study.

Students entering Dartmouth in the fall of 1939 could note its curricular philosophy in the College catalog. Referring to the Dartmouth curriculum, the catalog noted that "flexibility has long been one of its characteristics, so that courses of study and requirements for the degree might change to meet the changing needs of the day." This has certainly been the curricular objective throughout the century; perhaps the best that we can hope is that we will continue to be flexible even as we debate just what are the "changing needs of the day."

James Wright is deanof the faculty and aprofessor of historyat Dartmouth.

"Shreds and patches,"Leon Richardsoncalled core curriculain the early twenties.

Students got to chooseeven more of theircourses at the turn ofthe century, whenTucker was chief.

The curriculumshould "meet thechanging needs of theday," said thecatalogue whenHoppy was president.

Changes at theCollege helped moveLouis Morton'sfaculty committee todecide, against theGreat Issues course.

"The implicit assumption at Dartmouth has been that providing common knowledge is largely a function of secondary schools."

"The issue can be ideological as well as intellectual."

"Thefocus on relevance is fundamentally a non-issue... It would be hard to justify either a curriculum or an institution that was not profoundly relevant."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

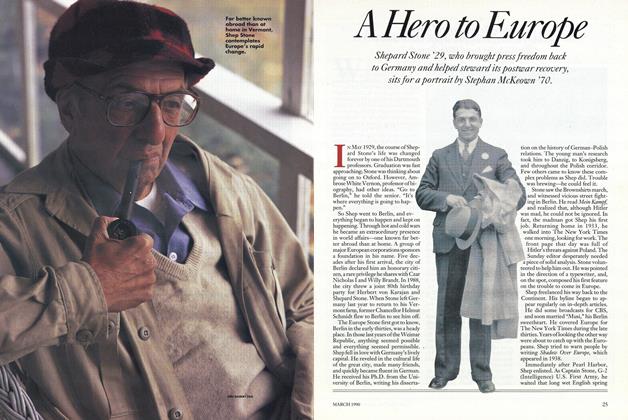

FeatureA Hero to Europe

March 1990 -

Feature

FeatureADDICTED TO CONVERSATION

March 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Feature

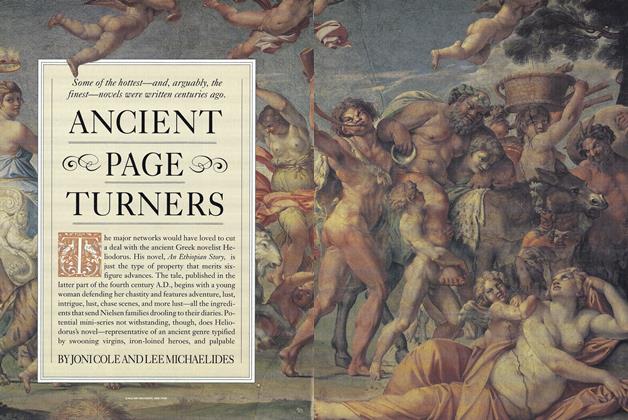

FeatureANCIENT PAGE TURNERS

March 1990 By JONI COLE AND LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeatureThe Purpose Gap

March 1990 -

Feature

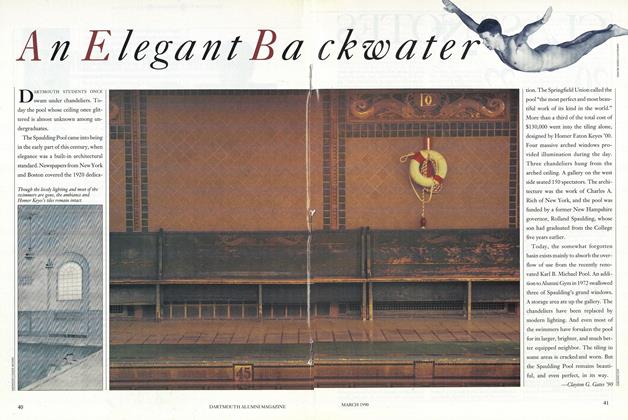

FeatureAn Elegant Backwater

March 1990 By Clayton G. Gates '90 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

March 1990

James Wright

-

Books

BooksFrontier Plans and Dreams

May 1980 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND REMEMBRANCE

December 1995 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Productivity

March 1996 By James Wright -

Article

ArticleThe Best of Both Worlds

DECEMBER 1998 By James Wright -

Interview

Interview"We Expect Excellence"

May/June 2005 By James Wright -

notebook

notebookGood Neighbor

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By JAMES WRIGHT

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHE MOUNTAINEERS

Jan/Feb 2013 By BROUGHTON COBURN -

Feature

FeatureThey're Putting the D in Debating

April 1955 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

Feature"Spoiled Children" of Hanover: A Letter from Charles Doe, 1849

MARCH 1959 By JOHN P. REID -

Feature

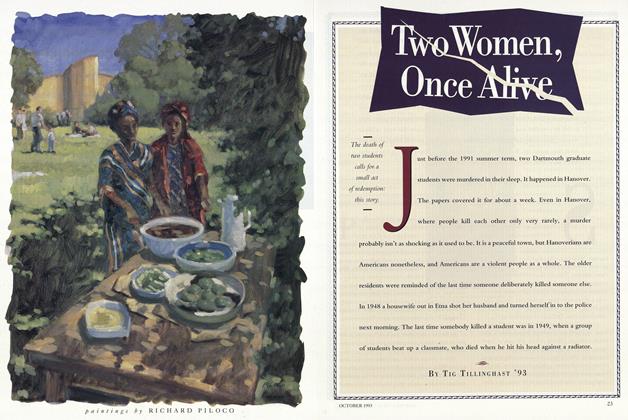

FeatureTwo Women, Once Alive

October 1993 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Feature

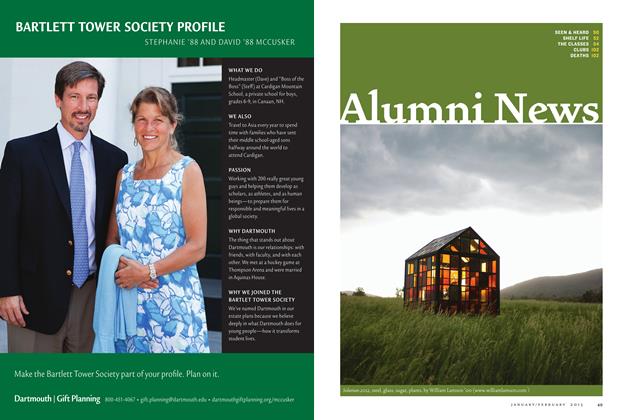

FeatureAlumni News

Jan/Feb 2013 By William Lamson '00