German unification was easy. Making it work is the hard part.

In the initial heady days of talk about German reunification, all things seemed possible. The East German pro-reform slogan "We are the people" rapidly transformed into the euphoric pan-German "We are one people." But the rhetoric has a long way to go before it becomes reality. Unification has proven to be more protracted and burdensome than either side realized or was willing to admit when the Berlin wall fell. A sobering reassessment of differing expectations and experiences has set in on both sides. "A lot of things we have to go through are downright humiliating," an East German recendy told me. "How often do you think a person can say thank you in one day?"

Germany faces a multitude of challenges. Bringing the standard of living in die East into parity with the West is a problem that will be solved in the end. Far more difficult is the question of what the new Germany will be. Will it blend East and West, or will unification amount to a merciless one-way flow of Western economics and culture solely controlled by the interests of the West?

Rampant westernization is already raising resentments and suspicions. For example, it makes no sense to workers from the East for their jobs to be cut on the grounds that they are unprofitable when at the same time, in the West, billions of marks subsidize such uneconomical branches of industry as coal mining and shipbuilding to keep them artificially alive and maintain jobs. In academia, long before 1989 many Eastern professors distanced themselves from the official party line in their teaching and research without breaking openly with the system. Now they are puzzled to see that their departments and research institutes are closed down and then reopened only so that the"new" positions can be filled by Westerners. Such inequities have led many Easteners to question the reliability, seriousness, and ultimately the credibility of the West.

On the other hand, Germany faces a lack of individual initiative and entrepreneurial mentality on the part of many Easterners. Under their centrally planned socialist economy, individual initiative had been considered fundamentally wrong. In order to change this perception, management consultants from the West have been sent to the East to reeducate managers in all fields. What these consultants transmitted has begun to take effect. But Easterners considered the manner of the West German consultants to be arrogant and humiliating; an air of hostility remains.

The retrained managers in the new states are themselves a problem. As long as they were neither members of the secret police ("Stasi") or high party officials, and as long as they declare their loyalty to the democratic principles of wethe new state, they retain their former positions. But this has led to suspicion and insecurity on the part of employees, who know that these same peopletheir former socialist bosses—may try to settle old scores when they have to cut jobs to achieve capitalist leanness.

Yet another problem is the loss of some of the social benefits—child care, maternity leave, and health care among them—which were guaranteed by the socialist state. Many Germans consider those benefits to be a positive legacythe only one—that should have been adopted by the unified Germany. These people feel that the benefits were sacrificed too quickly to the capitalist system and that their loss is a sign of the East's having sold out to the West.

Unification has been particularly difficult for the youth of the East. For them the disintegration of East Germany has meant the loss of a collective identity. Until now they were assured training and jobs merely on the basis of party membership. The skilled workers among them will find jobs in the new economy, but for an untrained minority the new conditions offer no promise. Their exaggerated hopes and expectations dashed by the economic hardships of unification, many unskilled workers are left with an intense sense of being second-class citizens.

The frustrations of this minority, combined with the tendency of adolescents to seek public attention and the sudden absence of the state mechanisms that formerly held that urge in check, have given rise to gang violence in the East. Behaving outrageously, flaunting Nazi symbols or, as happened at the Polish border, hurling rocks at foreign workers, these autonomous gangs are the Eastern version of skinheads. The media have portrayed these hooligans as signs of a burgeoning radical nationalism, but that is a distortion. This antisocial minority on the fringe of society—people without training or education—display Nazi symbols because they know that this act provokes strong reactions. In fact, gang members often are ignorant of the source and the meaning of the symbols they use. Their brutality toward foreigners stems from their misguided belief that this cheap labor force is responsible for their wretchedness. There is at present no regional or national organization to which these gangs belong, nor is there a neo-fascist national political agenda.

Still, the actions of gangs are alarming because they point to a potenitial for an eventual organization of extreme rightists in the Eastern states. No other country in eastern Europe experienced a spontaneous and total clash between a blossoming consumer society and a collapsing socialist state. This situation no doubt could lead to the recurrence of fascism, but the right-wing political potential has neither been tapped nor activated on a broader scale. The vast majority of Easterners accept the values of the Western law and constitution and believe in the idea of European cooperation. The stability of these values is vouchsafed by the last 40 years, during which German democracy has proven itself to be reliable and trustworthy.

In order not to jeopardize this stability, it is all the more imperative that Germany overcome the credibility gap between the East and the West. A speedy economic restoration is still the best remedy. But it takes time to form two different mentalities into one and create mutual trust. A little less self-satisfaction and profit-oriented thinking on the Western side and a little more individual initiative and self-motivation on the Eastern side will go a long way. Otherwise the Berlin Wall will be re placed by something more divisive: the invisible barrier German writer Peter Schneider calls "the wall in the head."

No wall divides them, but Germansdo not yet see eye-to-eye, according toGerman Professor Konrad Kenkel.

When the Berlin Wall crumbled under the forces of unification, German national Konrad Kenkel par; ticipated in his country's history the way millions of the world's citizens did, observing from afar. "I was content to watch it from outside," explained the Dartmouth professor of German. "It was rather touching to see the wall coming down, but I didn't think I had to pack up and go."

But, he adds, had he been in Germany at the time of his country's momentous change, "I probably would have asked some questions about the speed of unification. The process was so fast that some things were plowed under—including an early attempt on the western side to understand some of the good of the socialist system, such as social benefits, security for women, the health system, and the care of pensioners and the aged. Immediately after the wall came down, the West German political machinery was transposed to East Germany. Now West German issues are being fought On East German battlefields."

Kenkel's critical concerns for the well-being of die united Germany's citizens derive from his being a native son. Born in 1938 in Tilsit, Kenkel grew up in Hamburg in West Germany. Following the example of his father, who taught German and history at the high school level, Kenkel took degrees in German and history at the University of Hamburg, then caught German to foreign students. After tutoring in Indiana University's foreign studies program in Germany, he was brought to Indiana to teach. He stayed four years, earned a Ph.D., taught two years at St Olaf, then landed in German Department in 1974. Kenkel teaches German expressionism (his research specialty), German culture and society, poetry, and modern German literatureincluding the genre of father-son novels in which a young generation questions the actions and mentality of their fathers during the Third Reich.

Beyond the Green, Kenkel is director of Middlebury College's intensive summer German School, and he regularly leads Dartmouth's foreign-study and language-abroad programs in Mainz and Berlin. "Dartmouth wouldn't be what it is without these programs," he says. "On campus we talk about diversity, but on these programs students are exposed to it."

Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

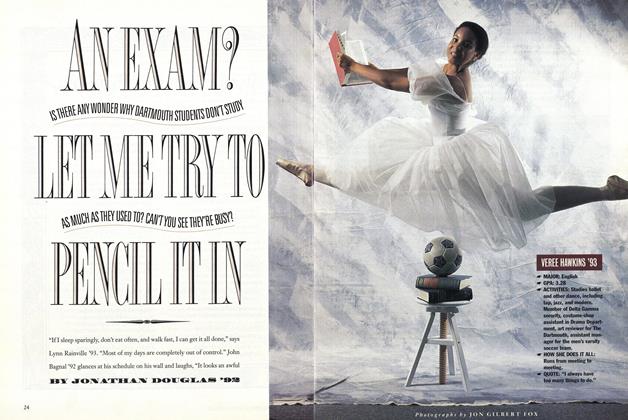

FeatureAN EXAM? LET ME TRY TO PENCIL IT IN

September 1991 By JONATHAN DOUGLAS '82 -

Feature

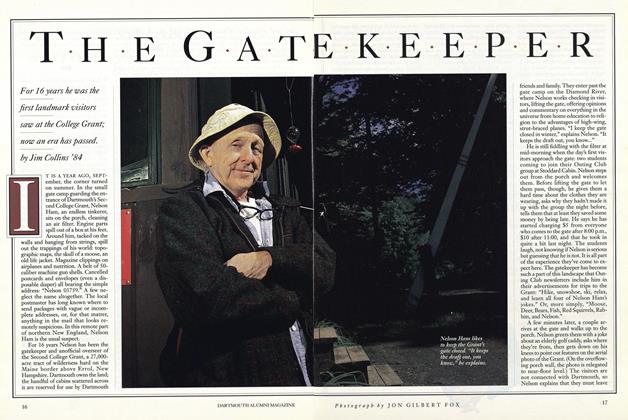

FeatureThe Gate keeper

September 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureELECTRIC BODY LANGUAGE

September 1991 By JAY HEINRICHS -

Feature

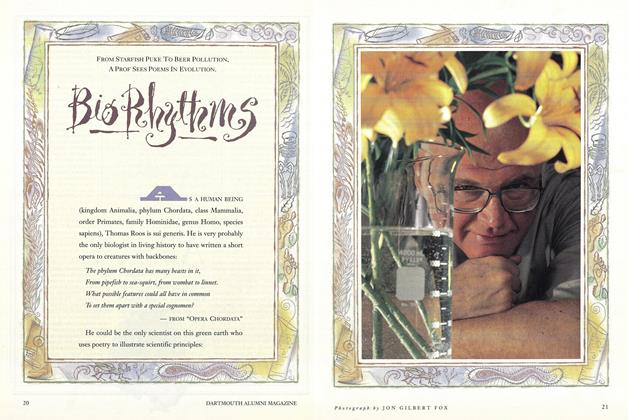

FeatureBio Rhythms

September 1991 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1991 By E. Wheelock -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

September 1991 By W. Blake Winchell

Article

-

Article

ArticleTENNIS

May 1919 -

Article

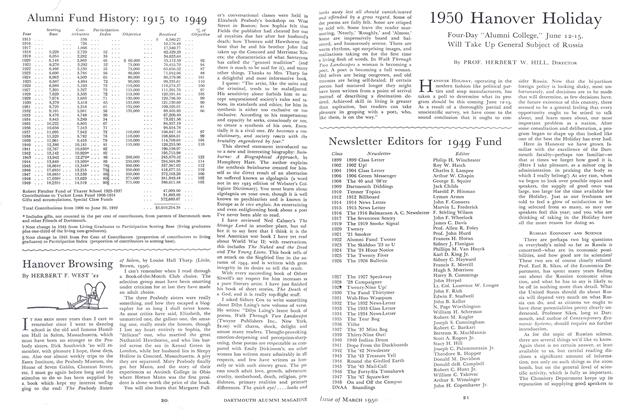

ArticleAlumni Fund History: 1915 to 1949

March 1950 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Article

ArticleNine Other Programs This Summer Range from Executive Decision-Making to Russian

APRIL 1963 -

Article

ArticleSeth Strickland '60

MAY 1968 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1942 By HERBERT F. WEST '22