IS THERE ANY WONDER WHY DARMOUTH STUDENTS DON'T STUDY

ASMUCH AS THEY USED TO? CANTYOU SEE THEY'RE BUSY?

"If I sleep sparingly, don't eat often, and walk fast, I can get it all done," says Lynn Rainville '93. "Most of my days are completely out of control." John Bagnal '92 glances at his schedule on his wall and laughs, "It looks an awful lot like I don't have time to go to the bathroom."

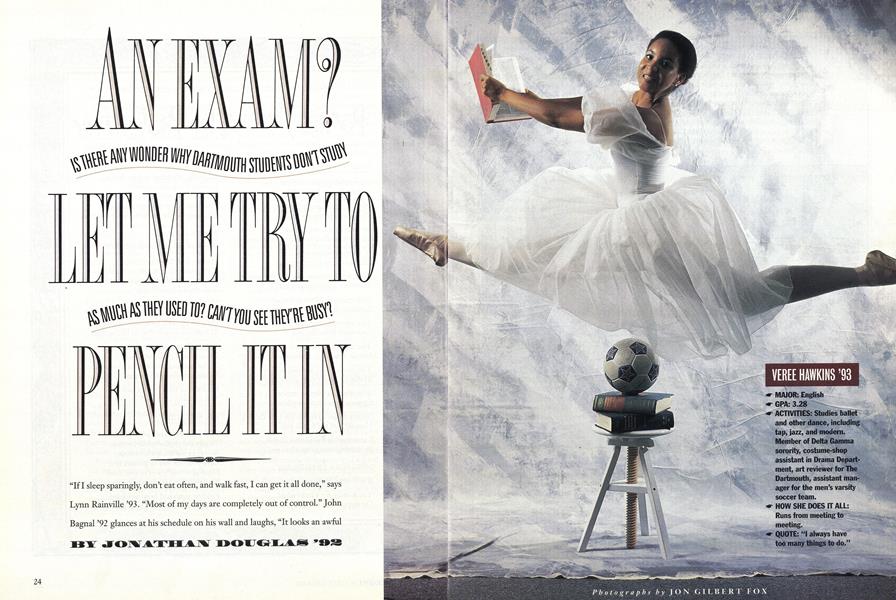

One Tuesday afternoon Veree Hawkins '93 scheduled a French class, a meeting with her Spanish professor, and a meeting with a dean all at the same time. "Somehow I was able to get everything done," she says in amazement.

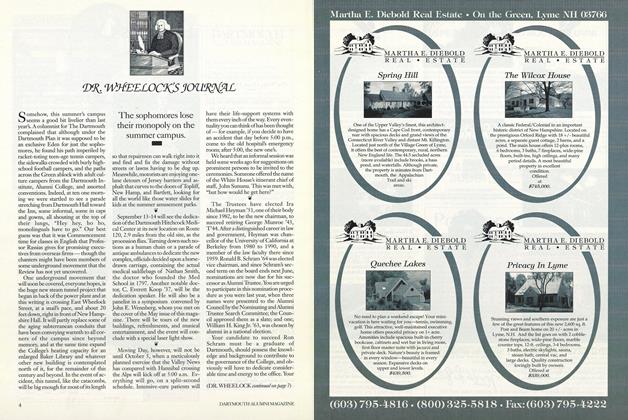

YOU THINK YOU WERE BUSY AS ASTUDENT? Look at junior Lynn Rainville (she's the blur going past you on the Green) .Last spring term, to give you a sample of her activities, she was publisher of an electronic environmental magazine called Sense of Place. She practiced Aiki Jitsu, a form ofmartial arts, for ten hours a week, and worked in the Baker archives for the same amount of time. She was a member of the Rockefeller Student Council, the Dartmouth Environmental Network Council, the Library Council, and the Outing Club. And, oh yes, she worked a double major in history and anthropology, maintaining a 3.6 average.

But Rainville is not the only one on campus with a busy schedule. "If you want to schedule a review session, students whip out their calendars," says Associate Professor of Anthropology Deborah Nichols without exaggeration. Today, more than ever, Dartmouth students are juggling academics, extracurriculars, work-study jobs, and social activities not necessarily in that order.

Where does all the time go? Sociology Professor Robert Sokol isn't sure, but he thinks he knows where most students' time is not going: into extra studying. Sokol, who has surveyed Dartmouth men over the last 25 years, has found that the average time spent studying outside of class per day decreased from 5.2 hours in 1961 to 3.2 hours in 1986. For all students, including women, study time shrank from 3.9 hours in 1982 to 3.3 hours in 1986. "Students today are just as competent as students from the early 19605, but they are less intellectually and academically committed," maintains Sokol. "Students at Yale, Harvard, and Columbia put in longer study hours than Dartmouth students."

One explanation may be that Dartmouth, unlike Harvard, Princeton, or Yale, does not require any of its students to write a senior thesis or a comprehensive exam; according to Thomas Bickel, registrar of the College, only 15 percent of Dartmouth graduates voluntarily complete honors projects.

But if Sokol's interpretation is correct, and Dartmouth students do less studying than their Ivy League neighbors, the natural question is why students here have so successfully resisted the call of the library.

Carl Thum, director of the Academic Skills Center, offers one answer. He reports that many students are unable to manage their schedules. "Students blow away so much of their time during the day," he says. "Students are immortal and see themselves as superhuman. They get so involved with activities at Dartmouth that they forget about their studying."

But even a superhuman would have a difficult time keeping up with the lives of some Dartmouth students. Athletics seem to be a prime culprit. According to Sokol's survey, only 34 percent of students believe that college athletics are "minor" to college life. And the Dartmouth Athletic Council reports that 85 percent of students participate in some form of intramural or intercollegiate sport.

"Some sports are very demanding," observes Dean of Freshmen Diana Beaudoin, who spends much of her time counseling students in trouble. "For a serious athlete, the time commitment can be anywhere from 20 to 30 hours per week. In essence, you can argue that we have many full-time athletes who are also part-time scholars."

John Bagnal, however, insists that his academics and crew complement each other. "I don't live, eat, and sleep crew," he says. "My extracurricular activities are so I stay sane. If I had to study all the time, I'd go crazy." He adds that "coaches are willing to give us time for academics."

On the other hand, Hannah Stith '94 admits to missing a few classes to attend diving practice, since they overlap by a half-hour. It's exactly this sort of schedule conflict that interferes with learning at Dartmouth, according to Associate Professor of German Language and Literature Susanne Zantop. She recalls one former student who was so involved with his running that he missed almost half his classes. A skier in another of Zantop's courses missed every Thursday to hit the slopes early. "I've been advised not to teach any afternoon classes because I won't get any students," Zantop says. "Too many are at athletic training."

But sports is clearly not the only activity taking up students' time. With well over 100 extracurricular to choose from (see the box on page 30), it is no wonder that academics must be squeezed into student schedules. College officials say this phenomenon of "busyness" is common to most selective colleges. But Carl Thum reports that Dartmouth's particular image tends to draw the kind of person who does everything, "a more active, people-oriented student" than the scholar at Harvard, Yale, or Princeton "who can't wait to get into the lab and mix chemicals and translate Latin."

The College's reputation for well-roundedness may be changing, however slowly. Since the arrival of President James Freedman in 1987, there does seem to be a renewed focus on academics. Freedman made an auspicious debut in his inaugural address to the faculty, when he called for increased student collaboration with professors on scholarly research. Nearly 100 students participate in a program begun on Freedman's watch, the Presidential Scholars Research Assistantships, which allow undergraduates to work directly with professors. And the community has lauded Freedman for new academic initiatives such as the Women in Science Program, which aims at attracting more women to careers in research.

But is Dartmouth truly attractive to the sorts of people who can't wait to get into the lab and mix chemicals? Sociologist Sokol says that the study habits of students haven't abruptly reversed themselves in Freedman's first five years; if anything, he says, the downward trend has continued. The problem, laments Economics Professor William L. Baldwin, is that the campus can be a bad influence on some: "We are taking very bright students who work harder than we know and putting them in an atmosphere that doesn't do enough to encourage the development of the intellect for its own sake and the development of education outside of career aims." Associate Professor of Music William Summers reports "a pivotal, profound, but pathetic moment" at a dinner he attended when two students sat shamefaced as they admitted to each other that they received citations for academic excellence. Dartmouth, says Summers, hasn't yet come to grips with the "vast untapped and unchallenged potential" among students who truly embrace the life of the mind.

Long-time campus observers list several factors that distract students from their studies:

THE. DARTMOUTH Plan. The College's system of four ten-week terms appears to be a mixed blessing. "I continue to be amazed at how well Dartmouth students balance their calendars and schedules," muses Dean Beaudoin. For some, the D-Plan provides an opportunity to continue activities from high school. But on the other side of the coin, Beaudoin adds, the system allows less room for academic error. "Skirting the edges of passing or failing a course can happen much more quickly in ten weeks," she notes. Still, some students see the need for a short term. "If we were on a semester system I'd be dead," moans Odette Harris '91. "There's no way I could juggle more than three courses with my other activities." Lynn Rainville '93 says, "If terms were two or three weeks longer, I probably couldn't make it. They fit in with my biological clock perfectly." But Henry Spindler '92, a chemistry major, points out a compelling reason to go back to a semester system: "The D-Plan makes it difficult to stay on top of my science courses."

JOB HUNTING. STUDENTS GET "ALL BENT out of shape" about finding a job, especially in their senior year, says Carl Thum. In fact, 62 percent of the class of 1990 took a job immediately after graduation, with only 21 percent continuing their studies in graduate school (an additional 53 percent plan to become grad students within five years). Besides job interviews, which conflict with classes and cause problems for seniors, says Dan Nelson '75, dean of the College for upperclass students, there's pressure for students to prove themselves successful by landing a job which can also detract from academic performance.

Skip S tinman '70, former director of Career and Employment Services, says that although recent classes aren't as "frenzied" about jobs as during the booming mid-eighties, the demands on students in corporate recruiting can sometimes conflict with academics. Some students take two-course loads in the winter to compensate for the time spent in recruiting (17 percent of all seniors chose this option in 1991, compared with 19 percent in 1986, the height of the Wall Street craze). For underclassmen, finding a leave-term internship can be similarly time-consuming, especially during recessions.

RAPE INFLATION. THERE IS A PERCEPTION among students that they don't need to work hard because most professors give generous grades, believes Associate Professor of Anthropology Kirk Endicott. The students may be right; between 1958 and 1988, the average GPA on campus rose from 2.2 to 3.2.

This could explain why some students concentrate more on outside activities than on classes. "I've been told by deans and employers that it isn't so important that your GPA is high as long as you have the degree," says Becky Johnson '92. "But it is looked well upon if you have decent grades and a lot of extracurricular activities as opposed to just having good grades."

OMPUTERS. ACCORDING TO A STUDY released by the dean of the College last December, 94 percent of Dartmouth students own a computer and 73 percent use Blitz Mail, the Col- lege's electronic-mail system. The technology poses a trade-off for students. While word processors and other software save time, computer games can easily eat it up. A short break from a paper can quickly become an extended game of Risk, and before you know it, it's dawn and another night is wasted. Some students have even been suspended for their computer addiction; although there are no precise statistics, the deans say that being glued to the Macintosh is symptomatic of poor time management, which leads many students to unwanted "Parkhurst vacations."

IN a typical week last spring, the events office listed 13 sports events, nine films, six concerts, ten academic colloquia, and five public lectures not to mention the ongoing exhibits at the Hop and Hood. If students truly wanted to avoid the call of the library, public events at Dartmouth could keep them busy for weeks.

Dartmouth's diversity of activities is "an embarrassment of riches," says Dean Beaudoin. Yet one has to wonder about the priorities of students who spend more time writing for The Dartmouth or playing sports or attending Student Assembly meetings than studying. The bottom line is whether or not students are actually getting their $80,000 worth from the College. "Extracurricular are a very important part of college life at Dartmouth," says Ann Koppel '94. "I don't think a campus that studied more would be better. I would like to have more time to study, but that would mean giving up my extracurriculars and that's not something I'm willing to do."

VEREE HAWKINS '93 MAJOR: English GPA: 3.28 ACTIVITIES: Studies ballet and other dance, including tap, jazz, and modern. Member of Delta Gamma sorority, costume-shop assistant in Drama Department, art reviewer for The Dartmouth, assistant manager for the men's varsity soccer team. HOW SHE DOES IT ALL: Runs from meeting to meeting. QUOTE: "I always have too many things to do."

MAJOR: Engineering and studio ait modified with art history GPA: 3.25 ACTIVITIES: Ski Patrol; heavyweight crew, member of Alpha Chi Alpha fraternity, sporty writer for The Dartmouth, works at Collis Cafe, member of Freshman Council and Feldman Fund committee. HOW HE DOES IT ALL: Schedules his time in "chunks." QUOTE: "I toy to schedule my days so I am neither too busy nor too bored but somewhere in between."

JOHN BAGNAL '92 MAJOR: Chemistry modified with biology; pre-med GPA: 3.25 ACTIVITIES: Crew, Wind Symphony, Symphony Orchestra, Marching Band, Brass Quintet, Presidential Scholar Research Assistant, Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity, Dartmouth Outing Club, Fire & Skoal Senior Society. HOW HE DOES IT ALL: Keeps a spread-sheet-style note pad on his wall. QUOTE: "Sometimes I'm so tired that I dont have the motivation to get my studying done efficiently."

BEN VINSON '92 MAJOR: Double major in history and classica studies GPA: 3.78 ACTIVITIES: Research assistant in Spanish and History, fencer, taught a course in English as a Second Lan guage, studies at leas eight hours a day. HOW HE DOES IT ALL: Sleeps very little. QUOTE: "Studying is important, but it isn't everything."

ADAM LEADER '93 MAJOR: Math and computer science GPA: 3.07 ACTIVITIES: Photographer, writes on arts and sports for The Dartmouth, member of the sailing team, photographer for the Aegis, tutor in math and computers. HOW HE DOES IT ALL: Keeps a written schedule of deadlines. QUOTE: "Although activities are important to me, my studies are the most important thing I do here."

To write this story, senior Jonathan Douglas took sometime off from his studies as a music major.; a WhitneyCampbell Internship with the Alumni Magazine, writingfor two student publications, a work-study job in thelibrary, and participation in the Glee Club, MarchingBand, Pep Band, Wind Symphony, Student Liaison Officer program, and intramural softball.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

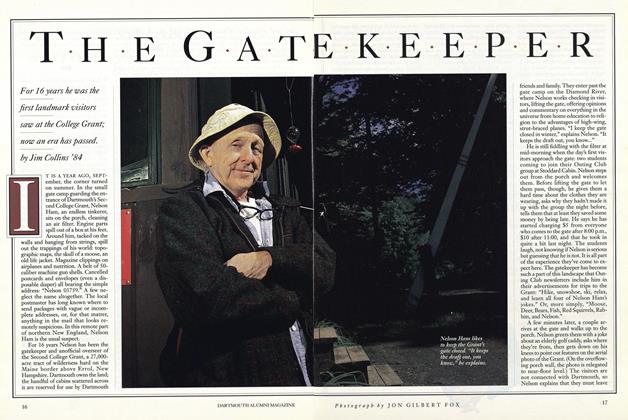

FeatureThe Gate keeper

September 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureELECTRIC BODY LANGUAGE

September 1991 By JAY HEINRICHS -

Feature

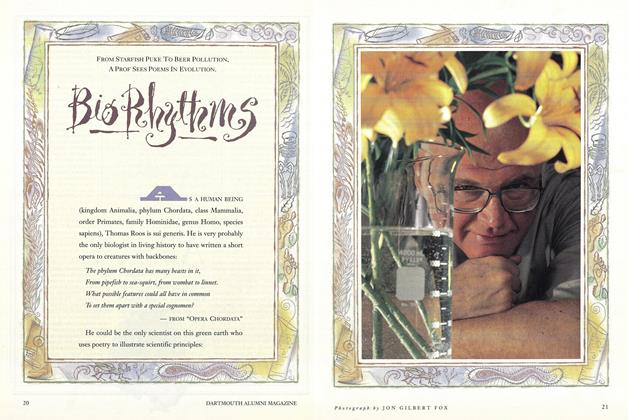

FeatureBio Rhythms

September 1991 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1991 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleAFTER THE WALL

September 1991 By Professor Konrad Kenkel -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

September 1991 By W. Blake Winchell

Features

-

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report

November 1961 -

Feature

FeatureThe Presidency

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureThe Best Class Notes of All Time

MARCH 1992 -

Feature

Feature"ring O bells!"

November 1974 By ELIZABETH F. MOORE -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY WOMEN?

OCTOBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BAKE A TASTY & AWARD-WINNING CUPCAKE

Jan/Feb 2009 By NORRINDA BROWN '99