For 16 years he was the first landmark visitors saw at the College Grant; now an era has passed.

IT IS A YEAR AGO, Semtember, the corner turned on summer. In the small gate camp guarding the entrance of Dartmouth's Second College Grant, Nelson Ham, an endless tinkerer, sits on the porch, cleaning an air filter. Engine parts spill out of a box at his feet. Around him, tacked on the walls and hanging from strings, spill out the trappings of his world: topographic maps, the skull of a moose, an old life jacket. Magazine clippings on airplanes and nutrition. A belt of 50caliber machine gun shells. Cancelled postcards and envelopes (even a disposable diaper) all bearing the simple address: "Nelson 03759." A few neglect the name altogether. The local postmaster has long known where to send packages with vague or incomplete addresses, or, for that matter, anything in the mail that looks remotely suspicious. In this remote part of northern New England, Nelson Ham is the usual suspect.

For 16 years Nelson has been the gatekeeper and unofficial overseer of the Second College Grant, a 27,000acre tract of wilderness hard on the Maine border above Errol, New Hampshire. Dartmouth owns the land; the handful of cabins scattered across it are reserved for use by Dartmouth friends and family. They enter past the gate camp on the Diamond River, where Nelson works checking in visitors, lifting the gate, offering opinions and commentary on everything in the universe from home education to religion to the advantages of high-wing, strut-braced planes. "I keep the gate closed in winter," explains Nelson. "It keeps the draft out, you know..."

He is still fiddling with the filter at mid-morning when the day's first visitors approach the gate: two students coming to join their Outing Club group at Stoddard Cabin. Nelson steps out from the porch and welcomes them. Before lifting the gate to let them pass, though, he gives them a hard time about the clothes they are wearing, asks why they hadn't made it up with the group the night before, tells them that at least they saved some money by being late. He says he has started charging $5 from everyone who comes to the gate after 8:00 p.m., $10 after 11:00, and that he took in quite a bit last night. The students laugh, not knowing if Nelson is serious but guessing that he is not. It is all part of the experience they've come to expect here. The gatekeeper has become such a part of this landscape that Outing Club newsletters include him in their advertisements for trips to the Grant: "Hike, snowshoe, ski, relax, and learn all four of Nelson Ham's jokes." Or, more simply, "Moose, Deer, Bears, Fish, Red Squirrels, Rabbits, and Nelson."

A few minutes later, a couple arrives at the gate and walks up to the porch. Nelson greets them with a joke about an elderly golf caddy, asks where they're from, then gets down on his knees to point out features on the aerial photo of the Grant. (On the overflow- ing porch wall, the photo is relegated to near-floor level.) The visitors are not connected with Dartmouth, so Nelson explains that they must leave their car at the gate and use the Grant for day-use only. "If you had a bumper sticker or even something green I probably would have waved you right through," Nelson laughs. He has already worked in two more of his jokes (both about pigs), and the couple is laughing, too. And that, Nelson says, is part of his job: making people happy not driving into the Grant.

It is a quiet morning, and at noon, exactly, Nelson puts the air filter aside and makes his way to the cramped kitchen of the gate camp. By comparison, the porch looks bare and organized. The gas lights and gas stove are jury-rigged with pipe at crazy angles, hung by string and joined by electrical tape, plugged in places with aluminum foil and pot holders. Bits of trivia and arcane information (1 hr. 37 min. fromhere to money machine and back. 9-15-88) are plastered on the door of the propane fridge. A 12-volt gas heater hooks into the crazy venting, and beyondthat, on a shelf above the kitchen table, a tangled mass of taped and spliced wires leads from two Diehard batteries. From the kitchen's center hangs a tattered Christmas ornament. Nelson pushes aside the unwashed dishes expanding out of the sink and prepares a simple meal of his own invention: creamed corn mixed with tuna. It is surprisingly good.

"People have called the gate camp a hovel, "Nelson says. "I just grab a dictionary and say, 'Oh, no it isn't. A hovel has a dirt f100r...'" He sets the dishes aside for later and points out the workings of his home-built power system. "The abysmal lack of mechanical ability is what strikes me," he says of the students who pass his gate. The jump in subjects is somehow easy to follow. "I feel as though I'm capable of doing anything, mostly because of where I've lived, I guess. Sometimes I can even fix things..." Before coming to the Grant, Nelson was the dam keeper at Errol, and before that, he did that same job for 14 years at the isolated Upper Dam near Rangely, Maine. Living there with his wife, Jean, and their daughter, with no road in and no visitors for months at a time, Nelson had plenty of opportunity to take things apart and put them together again, to make do with what was on hand and no one around to help him. The memories lead to one of his greatest sources of pride: his daughter, Betsy, who was taught at home through sixth grade, then went on to Phillips Andover, Dartmouth (class of '82), and got her master's at the University of Wisconsin.

Though his father was the head of Penn State's physics and chemistry departments, Nelson himself is largely self-taught. He was a radar operator and navigator in World War II before coming back to Maine, where his family had spent summers. At Upper Dam, then Errol, now the Grant, long hours alone have given Nelson the luxury to explore his many passions: he can quote scientific journals and Tennyson at will, and knows more about foreign countries than most people who have visited them. Next to tinkering and letter writing (he has written up to 40 letters a day, at times, to Dartmouth students, the Pope, Mao Tse-tung, and any person or corporation he might currently have a pet peeve with), Nelson likes to spend his time reading. He reads so much, in fact, that he calls himself a library and obtains books sent directly to him through inter-library loan.

All this has equipped Nelson to spar with his "educated" visitors at every available opportunity. He'll challenge them with an assumption about the finiteness of the galaxies or the belief that small airplanes not cars should be the way people travel. (He himself has an ultra-light plane he keeps nearby for the rare occasions he can leave the Grant and take off for a spin around the North Country.) He'll suggest a great practical joke say, dropping a planeload of tennis balls onto an abandoned tennis court just for people to ponder and then hope for an argument. Hearing none, he'll argue with himself or jump subjects to how, given any possible object, he'd want an air compressor with him on a desert island, or how maybe we should rethink the value of landfills and scatter our refuse over vast wilderness areas instead trying to draw the listener in, never once, one starts to realize, taking his subjects seriously. "Most of life," he says, making one wonder if this might be serious, "is essentially a joke. Would we have lost World War II if I hadn't gone?"

An hour after lunch, Nelson takes off his cotton hat and replaces it with a terry sweatband. He is 64, bald right down to his eyebrows, and shuffles in his walk as he does in his speech. But he is fit. With thousands of acres of woods and miles of trails surrounding him, Nelson prefers to stay out of the sun and get his exercise indoors. He prefers his Nordic Track exercise machine, on which he has spent 60 minutes every day for the past five years. A student in need of an adjustable wrench enters the cluttered camp and finds the gatekeeper with his shirt off, wearing wool socks, cutoff shorts, high-top leather sneakers, and a Walkman, moving in rhythm to worn-out tapes of the Beach Boys and "Peggy Sue." He motions the student to a wrench on the porch and completes his workout, not missing a beat.

APART OF THE GRANT'S foundation shifted two years ago. Nelson and Jean moved out of the gate camp where they had lived for 15 years down the littleused gravel road to the junction of Route 16, into a new house tucked between Mt. Dustan and the tiny Went worth's Location cemetery. Jean, who is the principal of Errol's 20-student school, was in charge of the construction, not Nelson. "You know, I had read about commuting and all that traffic," says Nelson, who now drives the mile of wooded dirt road between the house and the gate camp. "It has been quite a shock. I still can't get used to it."

There were other changes. Two new "self-service gates," workable with keys issued from Hanover, have been added in other parts of the Grant. These left Nelson, stationed at the main entrance from 7:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m., seven days a week, something of an anachronism. And so last spring the foundation shifted again, and with it, the era of the gatekeeper passed. A new, self-service gate was put in above the main entrance. The legendary gate camp was scrubbed clean and bare and a pay phone put in place of the clutter on the front porch. Nelson, no longer tied to the gate camp, was freed to roam the Grant for more thorough maintenance and inspection, freed to make reports back to Hanover first-hand rather than relying on what outgoing visitors told him. Freed to get to bed at reasonable hours on weekends rather than staying up for late arrivals.

But let us go back to last September for a moment. Staying up is exactly what Nelson is doing: it is nearly midnight when the final visitors approach. They are a group of four people, including a father and his six-yearold son. The lights in the camp are burning, and Nelson appears at the porch door in his slippers and bathrobe. After some brief small talk ("Hey, have I ever told you the one about the pig?" his fourth joke is never revealed), Nelson Ham gets down to what is important: he shows the six-year-old how to operate the counter-weighted rope that lifts and lowers the wooden gate outside, then steps back and watches the boy do his job. "You know," he tells the father, "it took me 14 years to figure out how to do that. I've taught some of the brighter Dartmouth students how to do it in two." Their laughter fades into the darkness, and for a moment, the only sound is the Diamond River as it flattens on its way to the Magal-loway. Nelson waves them good night, but not before giving the young boy one of the drilled-out machine gun shells from the belt hanging on the wall. Perhaps sensing what the gatekeeper has been to generations of young people before him, the boy holds it in his hands, like a treasure.™

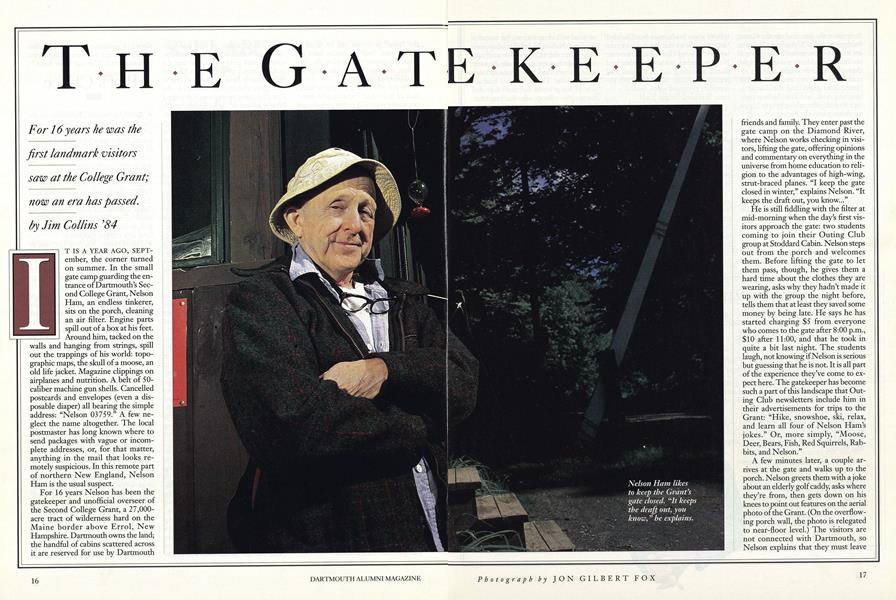

Nelson Ham likesto keep the Grant'sgate closed. "It keepsthe draft out, yonknow," he explains.

...AND ONE Of NELSON'S FOUR JOKES A man came upon a farmerholding a pig up to an apple tree.As the farmer lifted him, the pigwould pluck an apple off the tree,one at a time. After watchingthis for a while, the man said,"Wouldn'/ it save time if youshook the apples off the tree f Thefarmer put the pig down and said,"Mister, don''tyou know anything?Time don't mean nothing to a pig."

Jim Collins is a contributing editor to thismagazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

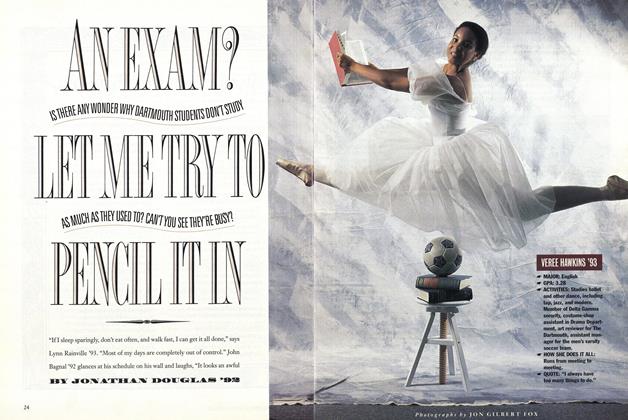

FeatureAN EXAM? LET ME TRY TO PENCIL IT IN

September 1991 By JONATHAN DOUGLAS '82 -

Feature

FeatureELECTRIC BODY LANGUAGE

September 1991 By JAY HEINRICHS -

Feature

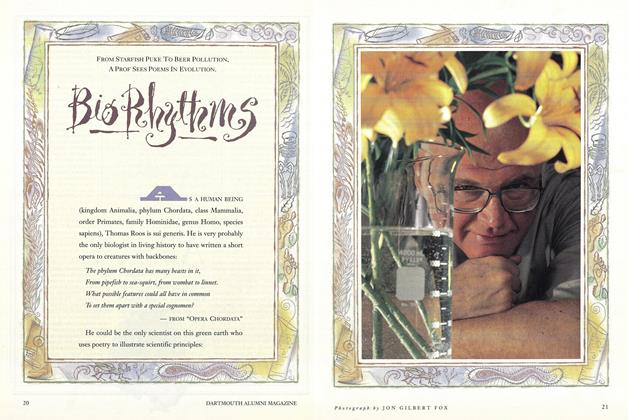

FeatureBio Rhythms

September 1991 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1991 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleAFTER THE WALL

September 1991 By Professor Konrad Kenkel -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

September 1991 By W. Blake Winchell

Jim Collins '84

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryBlack Dan's Reunion

June 1989 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

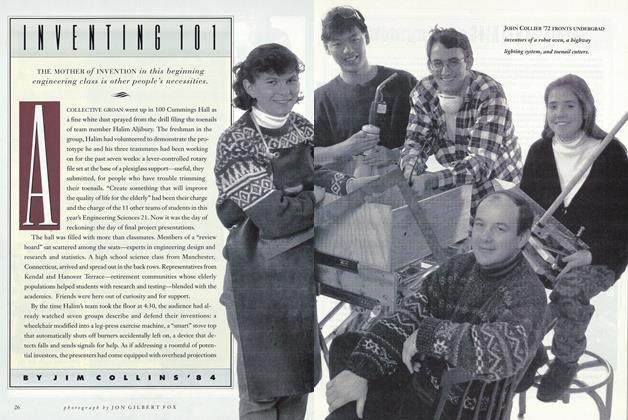

FeatureINVENTING 101

MAY 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleThe Lost Season

October 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleLandscapes of Murder

APRIL 1997 By Jim Collins '84 -

Cover Story

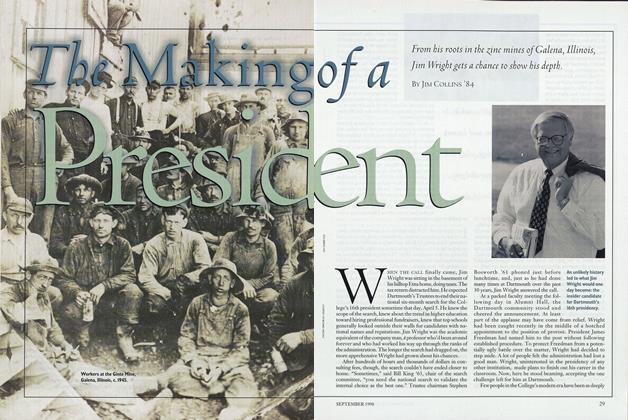

Cover StoryThe Making of a President

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Jim Collins '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGILLIAN APPS '06

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84

Features

-

Features

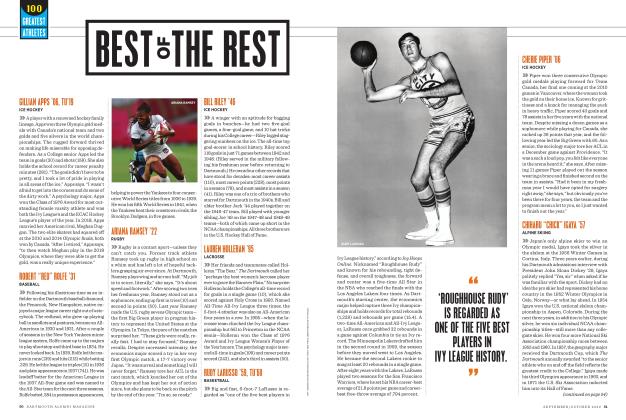

FeaturesBest of the Rest

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 -

Feature

FeatureCALLAHAN

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Frost's Shadow

SEPTEMBER 1997 By CLEOPATRA MATHIS -

Feature

FeatureJERRY

April 1961 By RICHARD F. VAUGHAN -

Feature

FeatureNaming the Animals

OCTOBER 1996 By Robert Pack '51 -

Cover Story

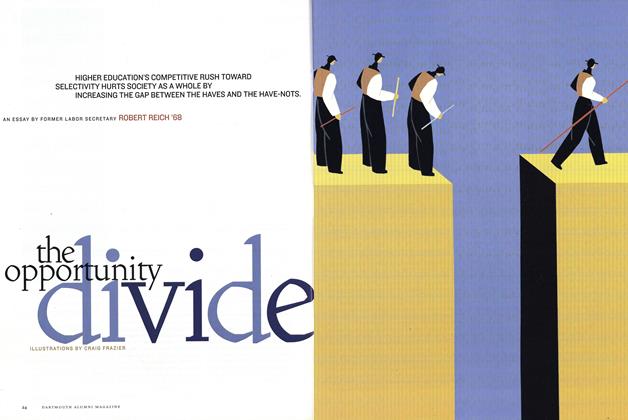

Cover StoryThe Opportunity Divide

Mar/Apr 2001 By ROBERT REICH ’68