The concept of John Dickey's stone was so simple, what mattered was the execution of the details.

ASA GRAPHIC DESIGNER the average shelf life of the ephemera I have produced ranges between one week and less than a year. But last year I was given a chance to make something that would last forever.

About a month after John Sloan Dickey '29 died, his daughter Sylvia wrote to me. "We would like you to help us with Dad's tombstone," she said. The quest was to last nine months, and it involved a tour of some of what John Dickey held dearest.

Like most of those who worked in the Dartmouth administration between 1945 and 1970, when John was President, I had gotten very close to the man and his family. When I returned to work for the College in 1956 as its graphic designer, the administration was still comparatively small, and John immediately made my wife, Anne, and me feel a part of that intimate group. Infused with the memories of that time—and with the courage of ignorance of the task, which I have been guilty of before with mixed success I plunged in.

Sylvia Dickey, whose nickname is Sukie, and I visited the site. John is buried in Pine Knoll Cemetery on a knoll next to the grave of his predecessor, Ernest Martin Hopkins 'Ol. The main Hopkins marker is one of the largest in the cemetery. It is quite formal and in a traditional style. We did not want to compete on any level. They had been good, longtime friends and we wanted them to rest in harmony throughout eternity.But they were very different men, and had administered two different Dartmouths.

With the words of the alma mater ringing in our ears, it seemed obvious early on to use granite for the stone. After looking unsuccessfully for material from some appropriate College building, we thought of the Second College Grant.As an undergraduate John had hunted deer in the Grant in northern New Hampshire, shire, hard by the Maine border, and like most people who had visited the place more than once, he had fallen in love with it. As its 12 th President he had made it a tradition to make a pilgrimage to the Grant after Commencement and reunions. There, with two or three of his good friends such as Ted Weeks, James Conant, Carlton Brewster, and his son John—they would fish for a few days. Young John would take them to their favorite spots in a canoe and then return to the cabin to cook dinner. They usually fished alone. If the catch was meager, Chris Dickey had sent backup steaks and pies. John Jr. reports that they rarely discussed Dartmouth but ranged far and wide over the rest of the world.

Might there be a boulder the right size and shape in the Swift Diamond River where he caught, fought, and lost many a squaretailed brookie?

Looking ahead to the time when we would face the process of getting whatever stone we chose cut and inscribed, I went for advice to James A. Browning '44,former Thayer School professor, inventor of a new method of cutting stone with flame, and owner of a granite quarry in Enfield. He introduced me to Chance Anderson, an environmental designer. Chance and I, along with Gil Tanis'38, John Dickey's longtime executive assistant, made a scouting trip to the Grant, three hours north of Hanover. From Route 16 we entered the Grant's dirt road and, after unlocking the gate to the bridge, drove east for a mile along the Swift Diamond Gorge. The place looks as if it hasn't changed since Dickey was a student.

We parked at the Management Center, a two cabin compound. A bronze plaque set on a rock across the road identified the surroundings as the John Sloan Dickey Area. We walked along the road that skirts the Swift Diamond River for about a half a mile to a place where road and river converge. The Diamond flows straight to the west here. It is about 20 yards wide, two feet deep on the average, and punctuated with many boulders. The water doesn't tarry this time of year. It acknowledges the rocks with ripples and eddies and flat but swiftly moving pools on the downstream sides of the stones. The pools still contain trout which still rise to the right lures. The grassy bank slopes down from the road and would provide an access to the boulders we chose. We found a place where John had fished. It faced northwest, toward the center of the Grant's 27,000 acres. Over his shoulder John could see the stark twin pyramids of the Diamond Peaks. Looking up at the end of the day he could see the sun set over the pines.

Chance and I returned on June 5 with a geologist friend of Chances's, Tom Davis, and Ev Wood '38, who had fished those waters many times. We had arranged to have a log skidder and its operator, Steve Thomas, at the site to extract the boulders we had chosen from the river bed. Chance waded after Steve into the frigid water. Wrapping slings under the boulders and hooking them to the skidder's winch, in three hours Chance and Steve had four candidates up along the road—about the time it would have taken John Dickey to catch a like number of brook trout on an average day. The stones were delivered to the Browning cutting sheds the following week.

Chance Anderson put the smallest stone on his giant diamondtoothed saw and made a series of cuts to produce a number of inchthick slices revealing the interior texture. We also cut a core cylinder about three inches in diameter and a foot long from the bottom of a larger stone. The boulders were from the right place, and they were the right size and color, but their texture was too coarse to carve crisp letters successfully.

Mrs. Dickey and Sukie met us at Jim Browning's later that week. We sketched some designs, settling on the word DICKEY and the pine tree that I had devised as the logo for Dartmouth's bicentennial in 1969. We then went up to Jim Browning's office to look at samples of granite from other quarries of the right color but of finer texture. We found one. And since it came from the Rock of Ages quarry in Barre, Vermont, it would also have a Dartmouth-John Dickey connection. The Dickeys have long had a cottage on Lake Champlain in Swanton, Vermont, which they use in the summer and weekends during the rest of the year. The Dickey children spent some of their best vacations there with their father who also used it as a place where he could work on his famous speeches without interruption. Barre is on the road between Hanover and Swanton, traveled by the Dickey family. What is more, Rock of Ages is owned by the Swensons, a many-generation Dartmouth family.

It was decided to mount a slab of Barre granite into a recess on the natural face of the Swift Diamond boulder, and then have two smaller slabs set into the ground to the right of the large boulder. One would have John's fall name and dates and the other would be reserved for Mrs. Dickey.

I made a wooden full-scale model of the large granite plaque with a three dimensional basrelief version of the pine tree and the word DICKEY incised into it. We took these to the Barre Sculpture Studio and arranged to have Michael Sheehan carve the pine tree in the granite slab. While that was being done, Chance and I carved the recess in the anointed boulder.

Achieving an appropriate monument for John Dickey had become complicated. But the concept and design were turning out to be a matter of serene simplicity. Since it was so simple, the execution of the details became of paramount importance. Ninety five percent of the inscriptions on monuments these days is done mechanically by sandblasting. We wanted John's to be cut by hand by the best carver available.

Indirectly through Rocky Stinehour '50, who runs the Graphic Arts Studio in Baker Library, we contacted Frankie Bunyard in Boston. The work she had done for Harvard and Tufts was excellent. Sukie and I met at her studio with the large granite plaque with the pine tree and the two smaller ground plaques. Frankie anticipated no problems in carving DICKEY on the larger plaque but was not confident about carving the italic letters on the smaller plaques. She recommended that we use slate. "Do you have a sample?" I said. She pointed to the Brandeis plaque."Where did that come from?" I asked.

"Vermont Structural Slate in Fair Haven." Perfect: I knew its former owner, Edward S. Carpenter '29, a classmate of John Sloan Dickey. Ed Carpenter had donated a slate that was used to restore Eleazar Wheelock's gravesite in time for the Dartmouth Bicentennial. Ed was happy to help us make arrangements with the new owner, William Markcrow T'64. Soon two slate slabs were on their way to Boston to be carved by Frankie Bunyard.

Chance and I inserted the small plaque into the boulder. It was trucked to Pine Knoll and lifted into place by a crane. When the smaller plaques were finished Sukie and I drilled holes in the frozen ground and put them in place. To give the river boulder a setting similar to its origin, Sukie and I placed a swath of little stones from the beach at the Swanton cottage. On January 25, 1992, a small group of those involved with the project and their friends gathered at Pine Knoll for a viewing. Even though over the years not many of those who will see John Dickey's stone will know of its connections to his life's many facets, we like to think he would be pleased, and that he would appreciate the pleasure we have taken in the task. As Hoppy had done, he often quoted Robert Louis Stevenson's words at the end of the tale, "The Lantern Bearers": "But those who miss the joy miss all."

It seemed obvious early on to use granite.

John Scotford still lives inHanover.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSecond Chances

September 1992 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79 -

Feature

FeatureTo An Athlete, Aging

September 1992 By Mark Lange '84 -

Feature

FeatureCommunion With The High Places

September 1992 By Andrew Daniels '85 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

September 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleDEATH and DYING

September 1992 By Professor Sergei Kan

John Scotford '38

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Liberating Arts

November 1954 -

Feature

FeatureVisitors Honored With Degrees

October 1951 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GET YOUR NAME INTO THE GUINNESS BOOK OF WORLD RECORDS

Jan/Feb 2009 By LARRY OLMSTED, MALS '06 -

Feature

FeatureHow Much Government?

March 1954 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY -

Feature

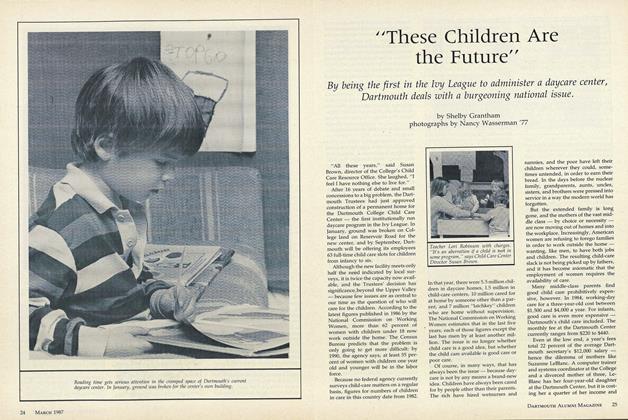

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

MARCH • 1987 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureAfter Iran: Can We Have a Foreign Policy?

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Stephen Bosworth '61