The courageous ones go where knowledge does not readily apply.And that, as Frost said, makes all the difference.

LONG BEFORE HE BECAME Secretary of State,Henry Kissinger said that the successful negotiator is the one who knows most clearly what he wants. Each spring I see students begin negotiations with their own destiny. It is time to look for a job and a career, and those with thoughts of journalism come to me. They mostly ask for alumni contacts; when I try to pass on Kissinger's wisdom, I become to them a human non sequitur. What does this man spouting Kissinger have to do with a job?

Yet here they are,striking a bargain with their futures, not knowing that the hardest part is bringing life to the table. Most of the students I see don't want to go into journalism—not really. Some want to be rap singers, or poets, or screenwriters, or owners of aggressive small businesses. They have a notion that journalism is somehow more legitimate than their dreams. Or, rather, the prospect of a profession promises an alternative, safer dream, the Great American one, for a decent house and a family and a new car and the respect of parents.

Much as an editor enjoys living vicariously, these junctures of desire unsettle me. I have no training in counseling and risk the charge of mentor malpractice, of impersonating a wise man.But the students I see aren't seeking advice, exactly. They talk to me as people talk to bartenders; I'm just a borrowed and sometimes sympathetic ear. Several years ago I received a call from Chuck Young '88, a former sports editor of this magazine, who said he needed some extremely fast counsel. "I just got accepted into Georgetown Law," he said, "and I have 'til five o'clock to get back to the Concord Monitor on a sportswriting offer. Which should I do: the newspaper or the law?"

I looked at the clock. It was just past 4:30. (Clearly, this man had one qualification as a journalist: he wasn't averse to deadlines.) "Have you called any lawyers?" I asked.

"No."

"Then you want me to tell you to take the sportswriting job. Take the sportswriting job."

"Thanks," he said, and he hung up and became a sportswriter.(He starts law school this month.)

For some students this initial choice will be the only life decision sion they make wholly on their own. Some are doomed to make a bad one; from what I read in Class Notes, they remain bound to the wrong life by ties to place or family or by lack of will. But most of the students I see merely commit a fallacy: that their decision is irrevocable. They don't see that our situations, our very bodies change, and a once wise choice can turn foolish with age. The negotiation with life never ends. Nature constantly abrogates the treaty.

The students I meet are standing on an abyss and looking for a parachute, not vague instructions. But instructions are the best I can give them, along with my blessing.

The instructions are these: to go where they know the least and can learn the most, to search for their joys.

And my blessing is this: may they find these joys more by design than by accident, and become rich more by accident than design.

Frost took the road less travelled by.

Jay Heinrichs is the editor ofthis magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSecond Chances

September 1992 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79 -

Feature

FeatureFishing The River For A Monument

September 1992 By John Scotford '38 -

Feature

FeatureTo An Athlete, Aging

September 1992 By Mark Lange '84 -

Feature

FeatureCommunion With The High Places

September 1992 By Andrew Daniels '85 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

September 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleDEATH and DYING

September 1992 By Professor Sergei Kan

Jay Heinrichs

-

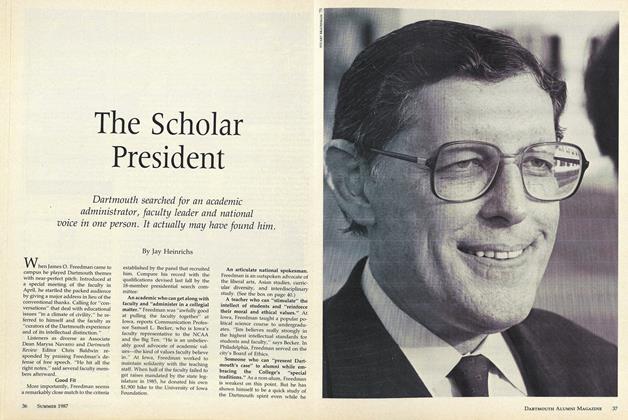

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

June 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCAN WE TALK?

MAY 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureFor The Sake Of Argument

February 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleBeyond Scrapbook

May 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Night Out on the Net

December 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Outside

OutsideRunning With Wild Abandon

July/Aug 2002 By Jay Heinrichs

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWHY a Hopkins Center at Dartmouth?

October 1961 -

Feature

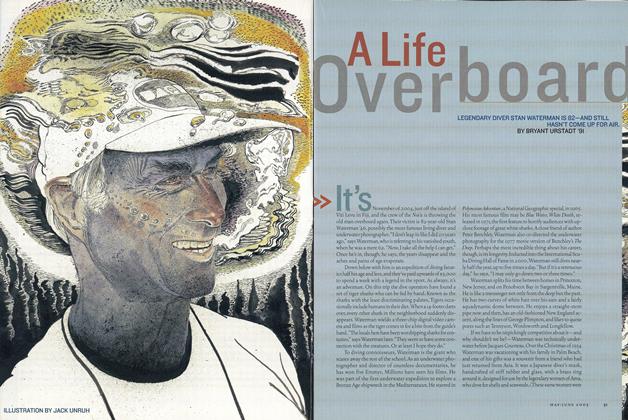

FeatureA Life Overboard

May/June 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySenator Paul Tsongas '62 Heading Home from Washington

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Douglas Greenwood '66 -

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

FeatureAn Honor, To a Degree

Sept/Oct 2002 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

FeatureRichard Eberhart at Eighty: The Long Reach of Talent

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Jay Parini