u. s. REPRESENTATIVE TO THE UNITED NATIONS

IN the broad range of everyday contacts with some eighty countries at the United Nations, where I work, there is a special satisfaction in working, as we have very closely over the years, with our British and Canadian colleagues. We do not always agree on everything, as everybody knows; and yet in a very profound sense we can understand one another because our values of life have so much in common. . . .

Even our difficulties make it clear that the alliance to which all three of our countries are committed is something very deep-seated and that it does - and must - transcend mere questions of temporary expediency. Respect for principles, for the rights of the individual, for the institutions of representative government, for tolerance, for religious freedom, for the right to speak one's mind, for the highest concepts of justice - these are all values which give meaning and worth to life and which lie at the base of our alliance. These things are eternal. The knowledge of them helps us to go ahead with hope and courage and thus to fortify and give effect to our friendship.

To accomplish this we must, first, frankly face such differences of opinion as exist and set about finding solutions for them. While the things which we have in common are more numerous and more important than the things about which we differ, there is no use, as Sir Harold Caccia said, in blinking stubborn facts of geography and economics which inevitably result in differing national policies from time to time. Let us, therefore, always be candid about such inevitable differences and not try to sweep them under the rug, not pretend that they do not exist, and thus not be pained and surprised when they come to light, as come to light they must.

To achieve this degree of constructive frankness there must be consultation. To be sure, our governments have always consulted. But in the shrinking modern world these efforts must ever grow in intensity and in the range of subjects which are covered. . . .

If, in spite of these efforts, there are differences on certain subjects, let them and the reasons for them be clearly understood so that we may each appreciate the other's position.

All of this will take much understanding, patience, and good will. But we in the United States believe that it will be well worth whatever trouble it takes, and further, that, once we have achieved this kind of a relationship, we face a future of great promise.

Our American confidence on this point is confirmed and strengthened by what we know about the character of our great allies.

As time goes on, the role of the United Kingdom, always great, is bound to become more and more important in world affairs. Among the enduring elements of British strength we count the confidence which the world has in the British sense of justice; their unsurpassed experience and skill in political leadership; their world-renowned achievements in industry and commerce; and their brilliance in science and technology, notably in the vast new field of atomic power. We look to Britain for all these qualities which are so essential for the progress of all.

We can, for example, easily imagine what British leadership and influence can do in the future in bringing about a more unified and integrated organization of European states. The possibilities arising from such union, when you stop to think about it, could do a lot of things: it could presage the end of the cold war; raise the general level of civilized conduct throughout the world; contribute to the dissolution of communism; and immeasurably advance the development of the world's sense of justice and it is on that development that permanent peace can be based.

In all of this Great Britain has a unique role to play, and in all of them she can count on the United States as her faithful ally.

No less do we look forward to Canada's continued contributions of wisdom, tact and influence in world affairs. We admire Canada's boundless energy which alone would assure her a future of greatness. We admire and applaud the Commonwealth relationship which she and Great Britain so largely originated, which they carry on so splendidly, and which has already done so much to shape the political map of the free world. In particular we cherish the neighborliness between Canada and the United States, which is truly unique and - I say this after four years at the United Nations - can well serve as a model of what international relations ought to be. . . .

And so, as I conclude, I come back to this point: that there must be between us more than a lowest common denominator of non-action. Britain, Canada and the United States must do more than just stand together; we must march forward together.

There are many incidents in history where boldness and determination turned out to be more important than sheer weight of power. Let not our preoccupation with weight of power, which is understandable and proper, cause us to lose sight of that fact. May our three nations always be in a position to act boldly and with determination. For this we must have a common, dynamic doctrine.

It is also important that we not be surprised; that we not be in the position of running here and there putting out fires which someone else has lit. For this too we need a doctrine which is dynamic.

We live in a world in which a majority of peoples are uncommitted as between the Communist bloc and the free nations like our own. We cannot expect these nations to share our view of the Communist threat if we remain constantly on the defensive. For this, too, a dynamic doctrine is needed.

In conducting foreign relations there must inevitably be guesswork, because foreign policy deals with the future. All the so-called "facts" are never available. There must therefore be faith; there must be a philosophy; there must be a way of thinking which is strong enough to give us the initiative, even though, unlike the dictators, we are not whipped up by fanaticism and by dogma.

In a moving and unforgettable speech in Britain's hour of danger in 1940, Sir Winston Churchill predicted the drawing together or, as he put it, the "mixing up together" of the peoples of Britain and America. You will remember the closing words in which he expressed his hopes for that great association: "Let it roll on full flood, inexorable, irresistible, benignant, to broader lands and better days."

Mr. Chairman, I said that boldness and determination can be more important than sheer weight of power. Sir Winston Churchill himself gave splendid proof of that truth. He thereby made it possible for our three countries to "roll on" through later years in a way which few observers, in that dreadful hour, would have dared to hope. Our future may still be full of danger and uncertainty but it is also full of promise, not only for our own peoples but for the universal human ideals which we shall always hold in common.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By SIR GEOFFREY CROWTHER -

Feature

FeatureOpening; Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE LEWIS W. DOUGLAS -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1957 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER -

Feature

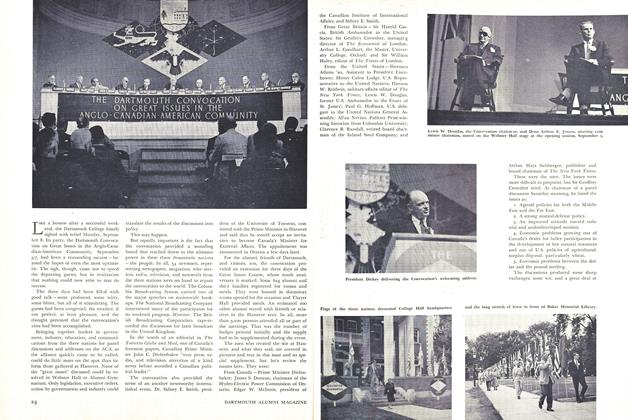

FeatureTHE DARTMOUTH CONVOCATION ON GREAT ISSUES IN THE . ANGLO – CANADIAN – AMERICAN COMMUNITY

October 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

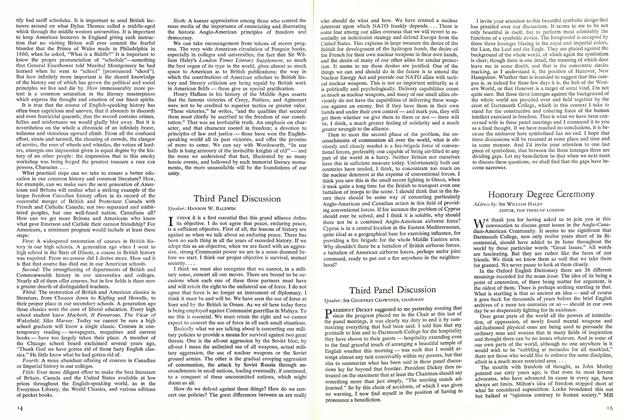

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1957 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1957 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSecond Panel Discussion

October 1951 By ARTHUR L. GOODHART -

Feature

Feature‘No reason... except faith' Ten Years of ABC

February 1974 By BRUCE KIMBALL -

Feature

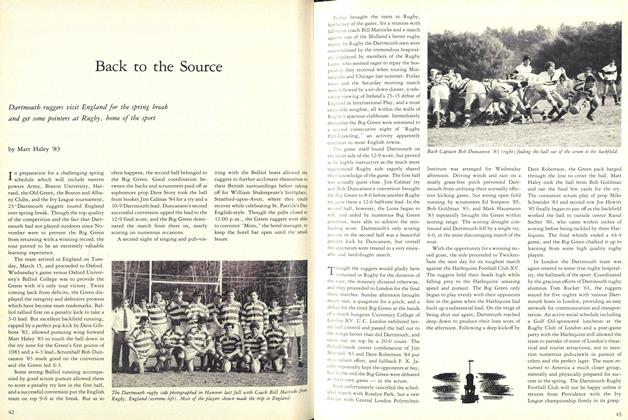

FeatureBack to the Source

MAY 1983 By Matt Haley '83 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dictionary's Function

May 1962 By PHILIP B. GOVE '22 -

Feature

FeatureA Rare Kind of Movie Star

October 1960 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52 -

FEATURE

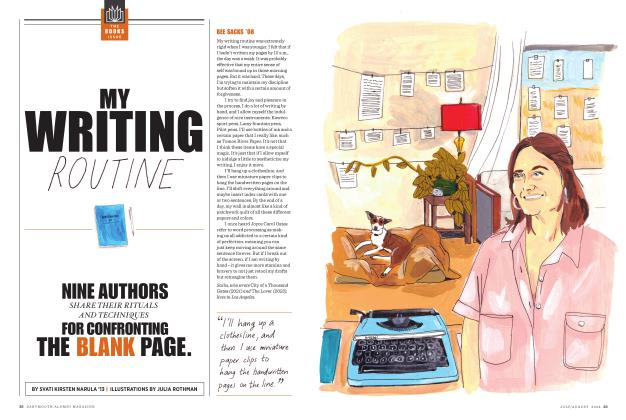

FEATUREMy Writing Routine

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13