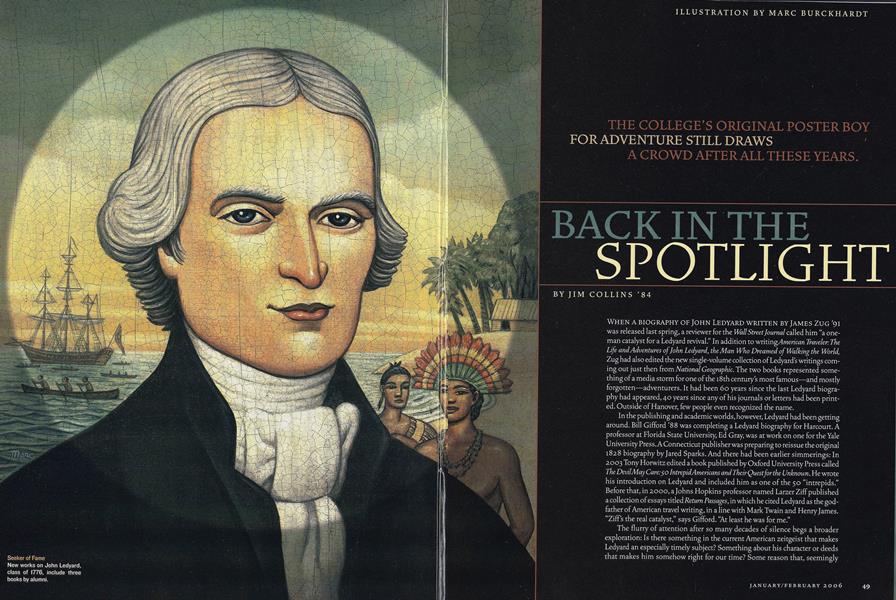

Back in the Spotlight

The College’s original poster boy for adventure still draws a crowd after all these years.

Jan/Feb 2006 JIM COLLINS ’84The College’s original poster boy for adventure still draws a crowd after all these years.

Jan/Feb 2006 JIM COLLINS ’84THE COLLEGE'S ORIGINAL POSTER BOY FOR ADVENTURE STILL DRAWS A CROWD AFTER ALL THESE YEARS.

When a biography of John Ledyard written by James Zug '91 was released last spring, a reviewer for the Wall Street Journal called him "a oneman catalyst for a Ledyard revival." In addition to writmg American Traveler: The Life and Adventures ofJohn Ledyard, the Man Who Dreamed of Walking the World, Zug had also edited the new single-volume collection of Ledyard's writings coming out just then from National Geographic. The two books represented something of a media storm for one of the 18th century's most famous—and mostly forgotten—adventurers. It had been 60 years since the last Ledyard biography had appeared, 40 years since any of his journals or letters had been printed. Outside of Hanover, few people even recognized the name.

In the publishing and academic worlds, however, Ledyard had been getting around. Bill Gifford '88 was completing a Ledyard biography for Harcourt. A professor at Florida State University, Ed Gray, was at work on one for the Yale University Press. A Connecticut publisher was preparing to reissue the original 1828 biography byjared Sparks. And there had been earlier simmerings: In 2003 Tony Horwitz edited a book published by Oxford University Press called The Devil May Care:50 Intrepid Americans and Their Quest for the Unknown. He wrote his introduction on Ledyard and included him as one of the 50 "intrepids." Before that, in 2000, a Johns Hopkins professor named Larzer Ziff published a collection of essays titled Return Passages, in which he cited Ledyard as the godfather of American travel writing, in a line with Mark Twain and Henry James. "Ziff s the real catalyst," says Gifford. "At least he was for me."

The flurry of attention after so many decades of silence begs a broader exploration:Is there something in the current American Zeitgeist that makes Ledyard an especially timely subject? Something about his character or deeds that makes him somehow right for our time? Some reason that, seemingly all of a sudden, there's a market for Ledyard?

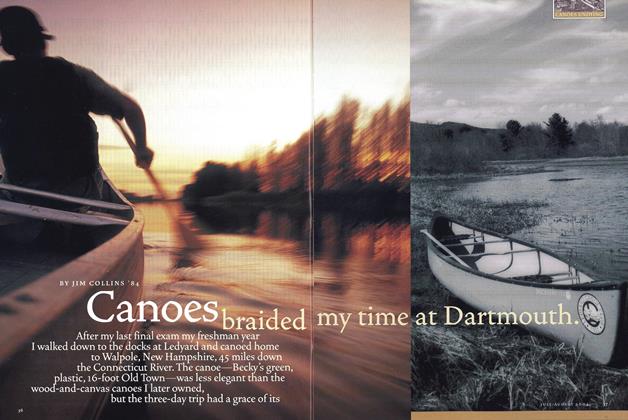

Within the Darmouth family, Ledyard is almost universally remembered as the legendary dropout who carved a dugout canoe in 1773 at the end of his freshman year and—armed with a few scant provisions, a Bible and a volume of Ovid—paddled 140 miles down the Connecticut River to home. (Dartmouth's canoe club, the oldest and largest in the country took on Ledyards name in 1920 and turned his downriver trip into an annual event. A plaque commemorating the man stands near the Ledyard Clubhouse, upriver from the Ledyard Bridge, a few minutes' walk from Hanover's Ledyard Lane and Ledyard National Bank.) But John Ledyards dramatic departure from Dartmouth was just the start of a life filled with dramatic, restless, pioneering adventure: He sailed with Captain Cook on Cook's illfated final voyage; became the first American to set eyes on the continent's west coast and to set foot in Hawaii and Alaska; trekked alone in the winter across Lapland and much of Russia; started the fur trade with China; befriended common seamen and nobility, natives and savages, Lafayette and John Paul Jones and Thomas Jefferson.

But history has remembered—or not remembered—Ledyard primarily for his failures, some of which were spectacular on a global-scale. abandoned his widowed mother and five younger siblings. He deserted the British Navy. The fur-trading companies he dreamed of creating were a bust. His ambitious plan to walk around the world was thwarted after 17 months and 14,000 miles when Catherine the Great had him arrested in Siberia, fearing that he was spying for the French government. Not long after that, at 37 years old, attempting to find the source of the Niger River, Ledyard died vomiting near the shore of the Nile River, barely out of Cairo. "His dreams were so large and impossible," writes Zug in the introduction to the National Geographic collection, "that people remembered the heartbreak more than mere distance traveled."

As did most former Dartmouth students, Zug first learned of Ledyard while an undergraduate. If he didn't share a kinship with the flamboyant, sulky-driving, Turkish pantaloon-wearing Ledyard, the two shared a certain wild spirit. Zug spent a lot of hours at Dartmouth out-of-doors and on the Connecticut (and later lived abroad for three years, in South Africa). He was part of the downriver trip some 15 years ago that inaugurated the so-called "Strip to the Sea"—the now-annual tradition of paddling past the Hartford skyline in the nude. As Eleazar Wheelock himself once said of Ledyard, that was "saucy enough."

Zug began his research on Ledyard in 2000. At the time he was freelancing for Squash magazine and doing book reviews for Outside and looking for a longer project that might be worthy of a book. The material he found in Dartmouth's special collections library fascinated him and gave him pause. There were original Ledyard journals, dozens of other original documents and letters, extensive papers of Ledyard scholars, undergraduate theses and a thick "alumni file" stuffed with miscellaneous articles and references. He saw the Sparks biography from 1828, the 1939 biography by Kenneth Munford, and the 1946 biography by Helen Augur. "None of the biographies was great to begin with," says Zug. "The last two, especially, were essentially valentines to Ledyard. The one from 1939 included created scenes and dialogue. Sinclair Hitchings '54, who attempted a biography in 1957, wrote a memo on the 1946 biography that said, 'Helen has fallen in love with him.' "

Zug saw the holes in the record and how elusive a character Ledyard was, but he also saw an opportunity. In the years since the last biography was written, additional volumes of Thomas Jefferson's letters had been completed, Robert Morris' published correspondence had clarified crucial details of Ledyard's role in the China fur trade, and the 1980 publication of letters from Siberian officers to St. Petersburg helped solve the mystery of Ledyard's arrest at the hands of Catherine the Great.

Zug talked with his agent, Joe Regal, about the possibility of a Ledyard biography. "There was no real sense in our minds," recalls Zug, "that the stars were aligning and that somehow the country was especially ripe for Ledyard. We were just excited that so little had been written recently about such a fascinating character. My book could have been written 10 years ago and the scholarship would have been the same; the reception, too, I suspect." Regal says, "I was astounded by Ledyard s life, and that so few people had heard of him. I didn't go to Dartmouth. But I also knew that we might be catching the current interest in Ron Chernow and David McCullough and the 'founding fathers' books."

Lara Heimert, one of Zugs editors at Basic Books, saw the same potential. "There's an incredible bull market for founding fathers books right now," she says. "And there's a bull market—at least for another year or two—for adventure travel. Ledyard hits them both."

Lisa Thomas, Zug's editor at National Geographic, thinks a big reason behind Ledyard's appeal is mystery. "We live in an age where most of the world has.been explored," she says. "Ledyard lived when entire sections of maps were marked 'unknown.' The explorers who ventured into those unmapped territories were incredibly brave. Their contribution to our understanding of the world is hard to comprehend today. And there's been a trend of books telling the history of an era through something that seems quite small, such as Cod or Salt, or any number of interesting nonfiction narratives that have been published in the past five or 10 years."

The current wave of adventure travel books started with the 1996 bestseller Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer, and it was Krakauer s agent, John Ware, who saw the promise in the Ledyard proposal that Bill Gifford submitted. A piece that Gifford had put together for Outside had earlier been nominated for a national magazine award, and Ware says the writing in the proposal spoke for itself. "But certainly," he recalls, "somewhere in my head something clicked in about the ongoing appeal of outdoor adventure. But mostly I liked the fact that Ledyard was an original character, starting at Dartmouth. He was legitimately the first American explorer. He was a relentless, almost compulsive explorer. He crossed paths with important American history and with historical discovery, and he seemed forever surrounded by an amazing cast of luminaries. He was the rock star of his generation."

"Mainstream historians have ignored Ledyard because he was a failure," says Gifford. "But he succeeded at being famous. Ledyard was the first American celebrity, or one of the first by my definition of celebrity. The ratio of his fame to his accomplishments was greater than 1:0. This was deliberate on his part, I think. He lived his life as if he were some sort of literary character. He didn't seem to care that his various adventures seemed guaranteed to kill him off. All that mattered was that his death be romantic, exotic, mysterious and tragic. He was a massive hero in the 19th century, his name known by every dreamy schoolboy. I don't know what Ledyard would be doing if he were alive today. Survivor? Blogging? Living off the grid in Oregon? I'm sure we'd all know his name, though."

'At his height," adds Zug, "Ledyard was famous for being famous. He wanted people to know where he'd been. He had tattoos from Tahiti put on his hands—not in some hidden place—so that everyone could see. Today he'd have his own press agent and corporate sponsors."

Ledyard, in that sense, may have been the first modern explorer. He was a professional explorer for hire, in it for the exploration and the glory. He wasn't funded by governments or scientific academies. He found his own money from businessmen and patrons, even going so far as to make up subscription forms. No explorer before him did those things, but others afterward would emulate him. He brought an unusually modern sensibility to his exploration. Americans at that young point in the country's history were concerned about creating a government and a sense of home, a sense of place. Ledyard was thinking globally. He was genuinely curious about the people he met in his travels and treated them as his equals. He learned native languages. He recorded journal entries from native perspectives. He wanted to make Americans aware of the people he encountered, that they lived in real places and cultures that were as valid as the ones he came from.

"Yes, he wanted to be famous," says Dartmouth professor of English emeritus William Spengemann, who had unsuccessfully shopped around a creative, reconstructed first-person Ledyard "biography" in the late 19905. "But he wanted to be famous for his service to humanity. That was Benjamin Franklins idea, too, the only justifiable fame. It was the perfect blend of egotism and high-mindedness."

Chip Rossetti, Zug's original editor at Basic Books, saw something refreshing in Ledyards global view. 'At the time I acquired the book," he says, "there was a lot of public discussion in the wake of 9/11 about how little Americans know or care about the rest of the world. Ledyard upended that stereotype. His story is so different from anything else we usually associate with early U.S. history. Tartar tribesmen and African exploration don't make much of an appearance in biographies about 18th-century Americans. Ledyards ideas about what it means to be an American are a refreshing antidote to some of the more inward-looking tendencies in American culture."

By 9/11 Gifford had been reassessing his own world. He had recently left his post as executive editor of Philadelphia magazine and was working as a freelancer, but he was looking for more freedom than magazine assignments allowed. "Ledyard kept popping up," he recalls, "and there was so little out there." He had first heard of Ledyard on his freshman canoeing trip, around a campfire on the banks of Connecticut between the Moore Dam and Fairlee, Vermont. "There was a point when I wouldn't have minded getting in a canoe and leaving Dartmouth myself," he says. "Instead, after I flunked a physics exam, I did it by car. I drove downriver and kept driving. For a few days I wasn't sure I could hack college. I think plenty of sophomores go through crises like that." As a writer years later, he wasn't sure he could hack writing a Ledyard biography, either. "Check out the Ledyard papers at Rauner," says Gifford. "He's defeated a half-dozen or more would-be biographers and novelists. I can see why these guys all failed. His romantic legend had been cultivated soon after his death—his first biographer was an upright Unitarian minister who left out Ledyards venereal disease and the 'fallen women of Paris,' among other things. Moreover, Ledyard plagiarized parts of his journals. He left a paper trail, but it's hard to recreate a life out of 21 surviving letters."

Given the gaps, Gifford turned his standard biography into a project that will be part travelogue, part literary biography, something different altogether. He reprised Ledyard's trip down the Connecticut River; retraced Ledyard's wanderings in France; sailed on the Endeavor, the replica of Cook's first ship; made his way to St. Petersburg and across Russia to Irkutsk. "I'm interested in Ledyard as a literary character," says Gifford. "I'm writing about legacy and context, about the construct of Ledyard."

The appearance of an imminent "Ledyard revival" might say more about the random nature of publishing or the doggedness and creativity of a few researchers than the subject himself, or maybe it's just coincidence. "To be honest," says Rauner Reading Room specialist Sarah Hartwell,who has overseen years of ongoing inquiries into that corner of Dartmouth's collection, "I don't think there's ever been a lack of interest in Ledyard."

John Ledyard just might, though, represent something about the American character that resonates still, something about restless spirit and individuality and our obsession with the endless horizon. Perhaps those themes resonate especially strongly today in our sedentary, patriotic, climate-controlled, technological, homogenized America. Maybe there is something there in the Zeitgeist.

In the end, maybe there's something simpler. After mentioning the publishing trends and the marketing reasons for bringing out a Ledyard biography right now, book editor Lara Heimert asks, "Isn't Ledyard's story the fantasy of every college student?" a

Seeker of Fame New works on John Ledyard, class of 1776, include three books by alumni.

Jim Collins, author of The Last Best League lives in Orange, New Hampshire.

"LEDYARD WAS AN ORIGINAL CHARACTER. HE WAS THE ROCK STAR OF HIS GENERATION."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

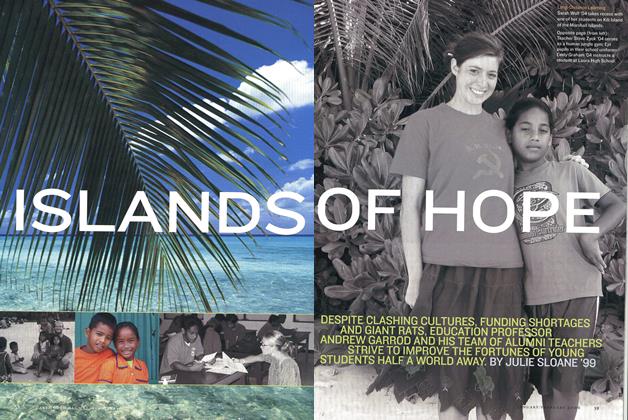

Cover Story

Cover StoryIslands of Hope

January | February 2006 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

FeatureHow to Win at Dartmouth

January | February 2006 By CAL NEWPORT ’04 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

January | February 2006 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

January | February 2006 By Gar Waterman '78 -

STUDENT LIFE

STUDENT LIFEDrinking It In

January | February 2006 By Barrett Seaman -

Sports

SportsGreat Skates

January | February 2006 By Mark Sweeney ’05

JIM COLLINS ’84

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryCanoes Undying

Jul/Aug 2004 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTEFishing With George

May/June 2010 By Jim Collins ’84 -

Feature

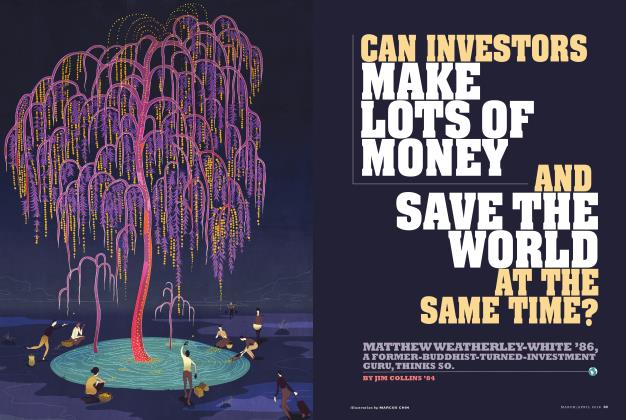

FeatureCan Investors Make Lots of Money and Save the World at the Same Time?

MARCH | APRIL 2018 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

FEATURES

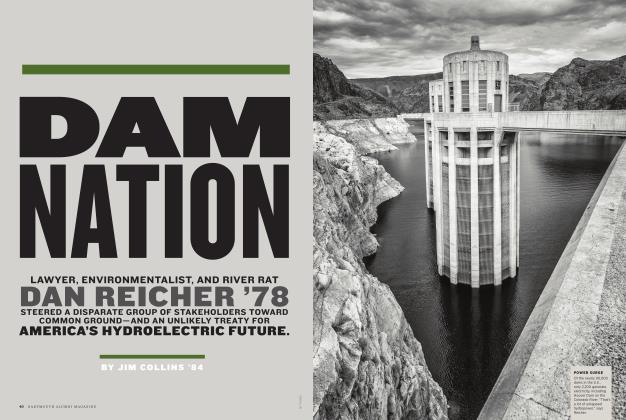

FEATURESDam Nation

MAY | JUNE 2023 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Features

FeaturesEveryday Zen

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

TRIBUTE

TRIBUTERemembering Earl Jette

JULY | AUGUST 2025 By JIM COLLINS ’84

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNovelist on the Go

FEBRUARY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureWhat Makes a College New?

February 1958 By BANCROFT H. BROWN, B. P., JOHN. NASH '60 -

Feature

FeatureOf Sun-Gazers and Seal-Hunters

JAN./FEB. 1978 By James L. Farley -

Cover Story

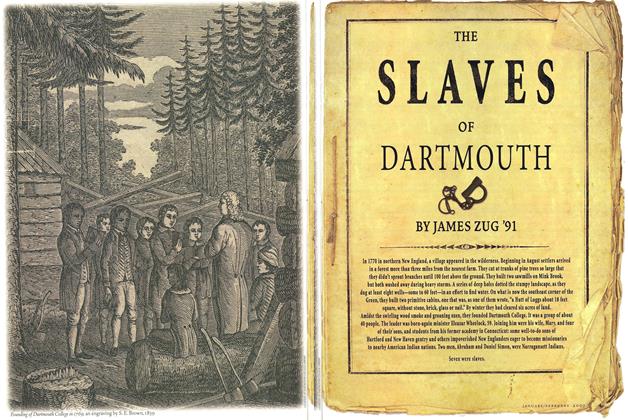

Cover StoryThe Slaves of Dartmouth

Jan/Feb 2007 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

Feature

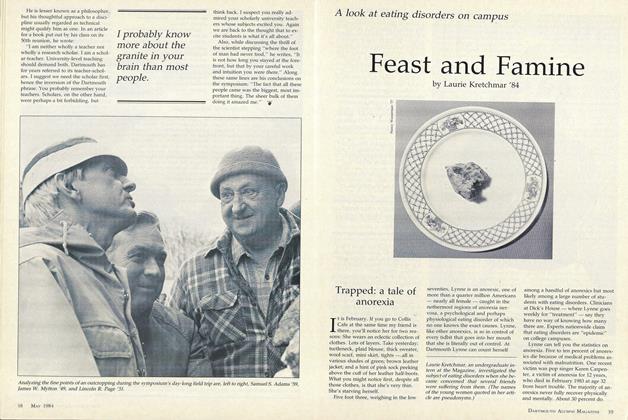

FeatureFeast and Famine

MAY 1984 By Laurie Kretchmar '84 -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: What Professional School Gives Credit for Throwing Pies?

NOVEMBER 1988 By Steve Lough '87