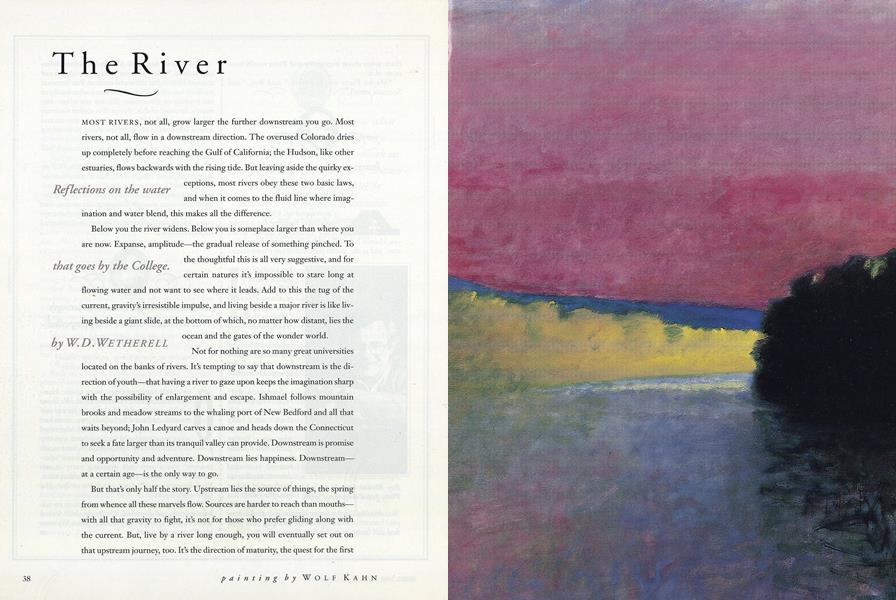

Reflections on the water that goes by the College.

MOST RIVERS, not all, grow larger the farther downstream you go. Most rivers, not all, flow in a downstream direction. The overused Colorado dries up completely before reaching the Gulf of California; the Hudson, like other estuaries, flows backwards with the rising tide. But leaving aside the quirky exceptions, most rivers obey these two basic laws, and when it comes to the fluid line where imagination and water blend, this makes all the difference.

Below you the river widens. Below you is someplace larger than where you are now. Expanse, amplitude—the gradual release of something pinched. To the thoughtful this is all very suggestive, and for certain natures it's impossible to stare long at flowing water and not want to see where it leads. Add to this the tug of the current, gravity's irresistible impulse, and living beside a major river is like living beside a giant slide, at the bottom of which, no matter how distant, lies the ocean and the gates of the wonder world.

Not for nothing are so many great universities located on the banks of rivers. It's tempting to say that downstream is the direction of youth—that having a river to gaze upon keeps the imagination sharp with the possibility of enlargement and escape. Ishmael follows mountain brooks and meadow streams to the whaling port of New Bedford and all that waits beyond; John Ledyard carves a canoe and heads down the Connecticut to seek a fate larger than its tranquil valley can provide. Downstream is promise and opportunity and adventure. Downstream lies happiness. Downstreamat a certain age—is the only way to go.

But that's only half the story. Upstream lies the source of things, the spring from whence all these marvels flow. Sources are harder to reach than mouthswith all that gravity to fight, it's not for those who prefer gliding along with the current. But, live by a river long enough, you will eventually set out on that upstream journey, too. It's the direction of maturity, the quest for the first cause—the small bang that sets things going.

Having turned 40 myself now, upstream is increasingly the direction of my explorations of the Connecticut trend. A whole string of discoveries here. The beautiful stretch above Newbury where the banks flatten just enough to let you see the White Mountains to the east; the rapids around Lyman Falls and Lemington, hiding place for some of New England's feistiest trout; the source itself, the meadow-fringed beaver pond with a name half as long as its breadth, Fourth Connecticut Lake...the odd feeling the whole high forgotten corner gives of a land attached to the rest of the country by the thin thread of the Connecticut alone. I've been heading up there often this year, the Northeast Kingdom's northeast edge, exploring the river in small doses—canoe length by canoe length, 15 gentle feet at a time.

IT'S ONE OF THE CURIOUS tricks of the human mind to assume anything possessing one name must have one invariable set of characteristics. I'm not immune to this; in writing frequently about the Connecticut I find myself trying to sum the river up, if not in one catchy phrase, at least in one memorable paragraph. But how do you link something thing that has by its banks both the village of Pittsburg, New Hampshire, and the city of Chicopee, Massachusetts? Where moose wade the upper stretches and cabin cruisers barge across the mouth? Where nuclear reactors share the floodplains with cows? Where recent miracles of restoration and renewal alternate with stretches that are still sadly spoiled?

The Connecticut itself is the link, and no words can substitute for that watery, all-encompassing locus. Living in the Upper Valley around Hanover, it's tempting to speak of the river as intimate and pastoral, even cozy (with all those kayaks and shells about, a Dartmouth version of the Cam), but that's a generalization that holds only as far as the lip of Wilder Dam, below which the river becomes something else again, and something else after that, and so on all the way to Saybrook 200 some miles to the south.

A river is the parts of its sum—there, that's the only generalization I'll risk.

I'VE BEEN LOOKING OVER a book I found in a second-hand store over in Norwich; hastily put out by the Federal Writers' Project in 1938, it chronicles the famous hurricane of that autumn, New England's worst natural disaster. Many of the black- and-white photographs are of a flooded Connecticut well over its banks. What strikes me, in staring down at them, is how recognizable the river is, even swollen; the same slow downstream impetus is there, judging by the direction the overturned trees are pointed; the surprising gray depth is there, too, gauging by its height against the the buildings of various downtowns. By its edges men are piling sandbags, but more than one of them—in fact, mostare pausing from their labor to stare in awe at the river swirling at their feet, confronted by the power of something they thought of as tamed, or more likely, never thought of at all. Pay attention, the water seems to be saying. Pay attention! The message it has for us today, though with the dams it's more apt to be delivered in a whisper rather than that loud desperate shout. Pay attention to what? Well, that's where words end, you need to get on the river yourself, sit and listen, sit and watch.

It's tranquil enough today, judging by the brief path of water I can see from the window of the room where I write. A few more words, and I'm off to explore it for the length of an afternoon; nothing new today, just touching base with sights, sounds, and smells familiar from river trips in the past. Soft alders overhanging the shore above Dartmouth's Ledyard Canoe Club; a bittern edging its way down the shoreline where Blood Brook comes in, close by the pine-covered bluff where sits the beautiful new Montshire Science Museum; beaver in one of those ramshackle lodges they build there, shaded by honeysuckle; rock bass sunbathing around the shallows by Titcomb Island; a hot-air balloon slanting down from the vicinity of Norwich, flirting with the river's surface, dipping toward it, then—with a sudden whoosh—rising again.

Upstream? Downstream? Youth? Old Age? For one short afternoon neither, but the fleeting moment balanced exquisitely in between.

"It's tempting to say that down-stream is the direction of youth."

W.D. WETHERELL, whose story collection, The Man Who Loved Levittown, won the Drue HeinzLiterature Prize for short fiction, lives in Lyme, NewHampshire. His most recent book is Upland Stream, acollection of essays about fishing. WOLF KAHN is oneof America's leading landscape painters. While artistin-residence at the College during Winter term of 1984he painted many views of the river between Hanover andLyme.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

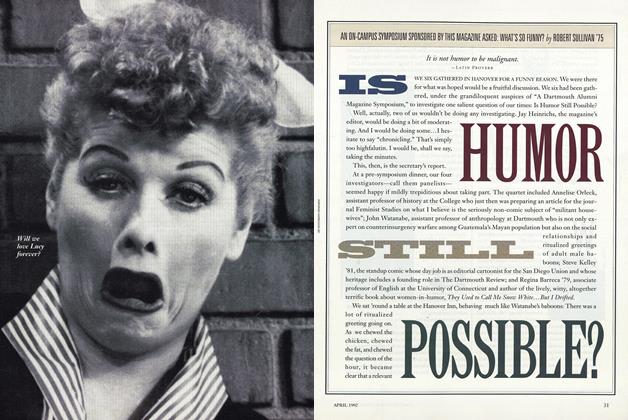

Cover StoryIS HUMOR STILL POSSIBLE?

April 1992 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

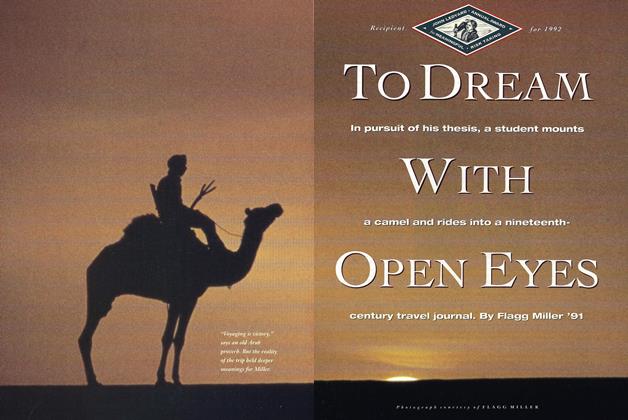

FeatureTo Dream With Open Eyes

April 1992 By flagg Miller '91 -

Feature

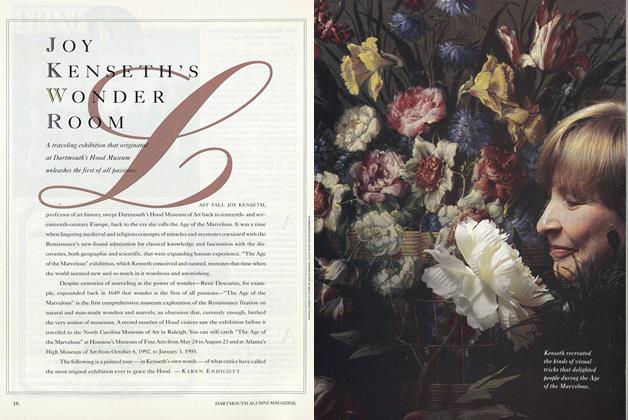

FeatureJoy Kenseth's Wonder Room

April 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

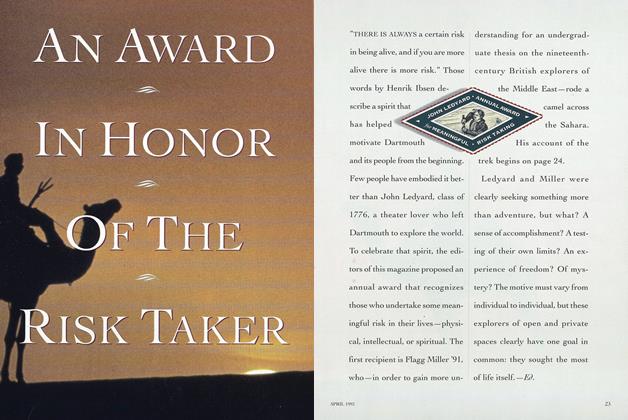

FeatureAn Award In Honor Of The Risk Taker

April 1992 -

Article

ArticleThe Imagination Unbound

April 1992 By Ulrike Rainer -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

April 1992 By "E. Wheelock"

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThey have been called freshies, Pea Greeners, shmen a current phrase that cannot be uttered without sneering.

September 1993 -

Cover Story

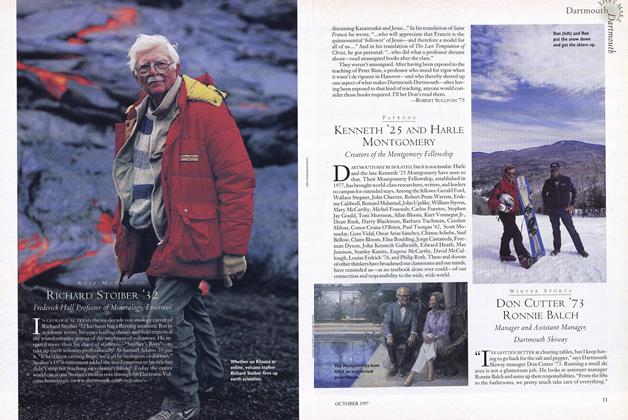

Cover StoryKenneth '25 and Harle Montgomery

OCTOBER 1997 -

FEATURE

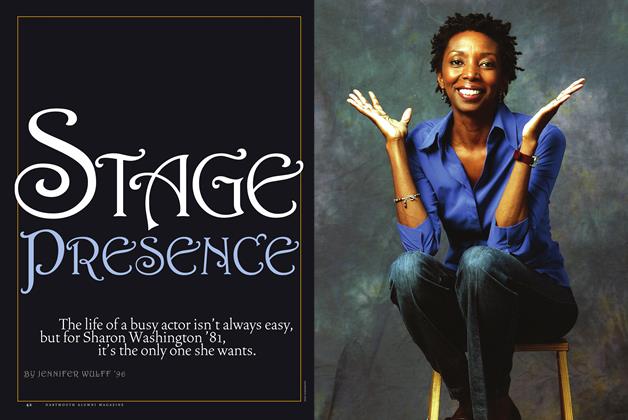

FEATUREStage Presence

Mar/Apr 2009 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Cover Story

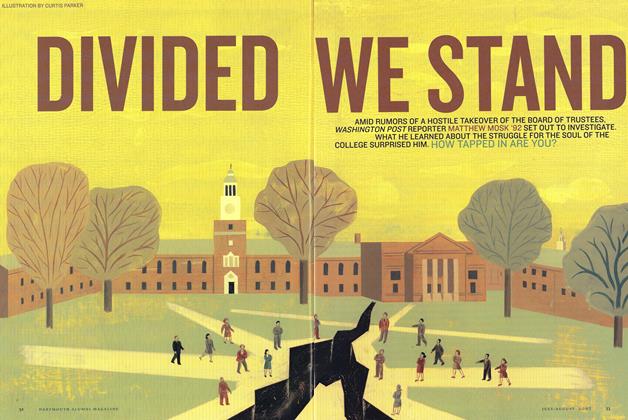

Cover StoryDivided We Stand

July/August 2007 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Cover Story

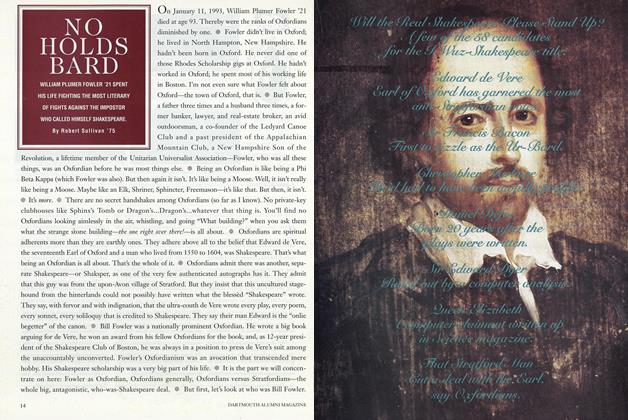

Cover StoryNO HOLDS BARD

MARCH 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

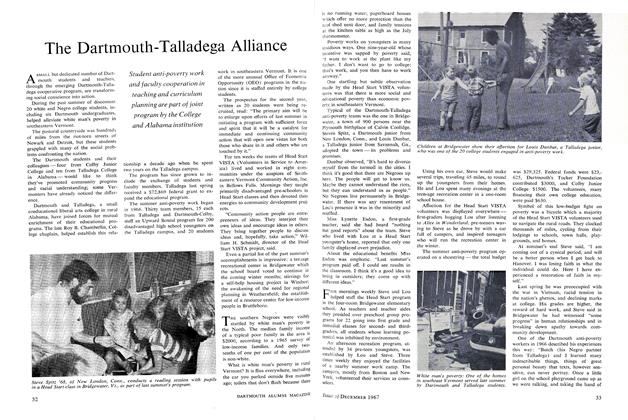

FeatureThe Dartmouth-Talladega Alliance

DECEMBER 1967 By WILLIAM R. MEYER