Tales of the uncanny and fantastic refocus reality.

WHEN I WAS A VERY young girl I perched in the trees of the Vienna woods and devoured my favorite books of fairy tales, myths of many nations and cultures, and ghost stories. I understood nothing yet about literary genres and scholarly endeavors. I had no idea that the formidable Russian structuralist Tzvetan Todorov was claiming that the fantastic in literature "is that hesitation experienced by a person who knows only the laws of nature, confronting an apparently supernatural event." Nor did I know of his distinction between the uncanny and the marvelous: "if the laws of reality remain intact and permit an explanation of the phenomena described, we say that the work belongs to the ... uncanny. If, on the contrary, [the reader] decides that new laws of nature must be entertained to account for the phenomena, we enter the genre of the marvelous." I was blissfully unaware of Sigmund Freud's pronouncement that the uncanny is "something which is secredy familiar, which has undergone repression and then returned from it." Unencumbered with theory, I was fascinated by stories which defied the laws of reason, commonly held beliefs, and societal norms all the things my parents and teachers told me to respect as "truth." Through the years I never lost the child's skepticism toward "unshakable" and "eternal" truths and the spirit of rebellion that clung to the belief that for every is there just might be a what if or an as if an idea that can only be thought and imagined but never asserted or proven with certainty.

Inexplicable and supernatural events have fuelled the imagination as long as human beings have been telling stories. Indeed, the human mind's infinite ability to envision inner and outer spaces beyond the known and measurable is the wellspring of creativity. Fascination with the fantastic and the uncanny has led to a rich and enduring literary tradition replete with fairy tales, horror stories, mysteries, and tales of psychological dread. For who does not, in defiance of reason and the strong human urge to find order in human existence and to make sense of the universe, at times doubt the powers of logic and scientific truth? We need a multiplicity of perspectives, including some which may go against all we have been taught or want to believe, if we want to explore and put into context our awareness of life's fragility and our questions about life's purpose, goals, and ultimate end. Swedish film director Ingmar Bergman, an astute explorer of the uncanny and the fantastic, sums up these questions simply and succinctly in the introduc- tion to his film "Face to Face," a work which probes the darkest corners of the unconscious: "Actually [the film] deals ('as usual' I was about to say!) with Life, Love and Death. Because nothing in fact is more important."

If all of this sounds terribly serious and gloomy, let me assure you and I usually manage to convince my students that a great deal of irony and humor permeates the best of fantastic and uncanny stories. Metaphysical questions and quests need not depress us. Fantastic and uncanny tales can be funny and entertaining. They are a good read, books we simply can't put down, because most of all we want and need to know what happens to the enchanted frog, the mad young man who loves an automaton, the traveling salesman who wakes up one morning and finds himself transformed into an insect, the vain Russian upstart whose nose leaves his face to assume an independent existence as a state councillor. Not until we finish reading are we able to reflect, search for more meaning, and decide what the story really wants to tell us.

Our students understand instinctively this interplay between the sheer pleasure of the plot and its hidden message. My colleague Laurence Davies, an expert on and inexhaustible source of fantastic and uncanny tales, tells of personally experiencing such student reactions. "A few years ago, when it turned out that I sympathized with the vampire in my opera," he says, referring to a libretto he had written, "students were crossing themselves every time they met me, and proffering bulbs of garlic." I think such lighthearted gestures prove the point nicely: we take your joke seriously, the readers seem to say, but only in the vast kingdom of the imagination. We do, however, understand and appreciate the serious business behind the joke.

Indeed, very serious business hides behind the seemingly impossible, the bizarre, the absurd, the terrifying, the marvelous. Under such disguises, authors skillfully and often also playfully manage to address and manipulate our darkest fears, deepest secrets, and forbidden pleasures as they explore the question of what it means to be human. Hans Christian Andersen, the Danish teller of fairy tales, challenges us to think about the essence of humanity when he gives us a little mermaid's tragic quest for the most elusive of human qualities: a soul, with its ability to shed tears, to love and be' loved. Similarly, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein asks how monstrosity distorts humanity. Is it at all possible to understand an "other" when our vision and perceptions are solipsistically limited or clouded by prejudice? Are we able to see the future graceful swan in the awkward ugly duckling, the beautiful woman underneath the dirty kitchen rags, the righteously vengeful ghost in the body of Nicolai Gogol's unassuming hero in "The Overcoat"? And conversely, are we able to detect ugliness and evil when it is covered by respectability and a flashy officer's uniform as in Franz Kafka's "In the Penal Colony" or lurking behind the beautiful features of Edgar Allan Poe's "William Wilson"?

In the realm of the fantastic, writers dare to describe things they never could have addressed in realistic terms. How else could they explore such tabooed subjects as unacknowledged sexual longings, homosexuality, incest, and necrophilia? The motif of incest in Ambrose Bierce's "The Death of Halpin Frayser" appears in the guise of a hair-raising ghost story. If the genre permits us to circumvent external and internal censorship in such matters, it also eludes censorship of a different kind. Gogol could not have criticized Russian society and politics so harshly had he not done so within the context of the hilariously absurd story "The Nose," nor would we find "The Emperor's New Clothes" so funny were the character not fictitious. Consistently our stories point to the very act of creativity itself. If anything and everything is possible in the writer's imagination, then perhaps we can learn to stretch and challenge our own and learn to question the nature and limitations of our perceptions.

As if all this were not reason enough to read tales of the uncanny and the fantastic, there is something else. I love good stories. Teaching them gives me an excuse to read and reread them and be up there in the trees again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

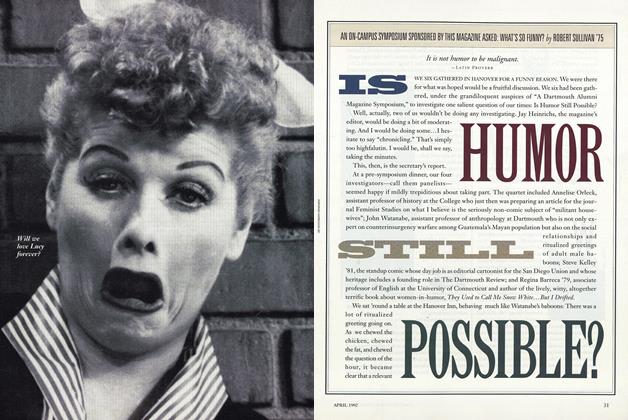

Cover StoryIS HUMOR STILL POSSIBLE?

April 1992 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

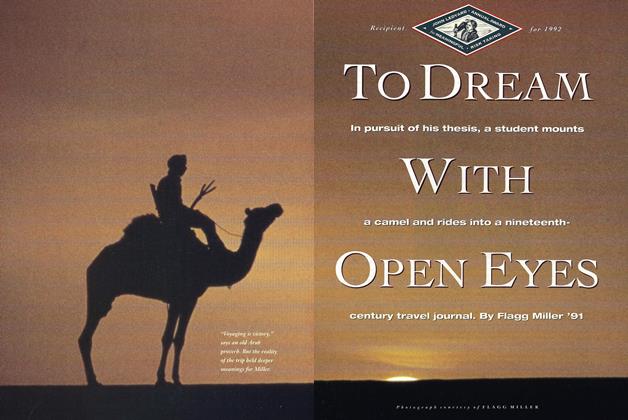

FeatureTo Dream With Open Eyes

April 1992 By flagg Miller '91 -

Feature

FeatureThe River

April 1992 By W. D. Wetherell -

Feature

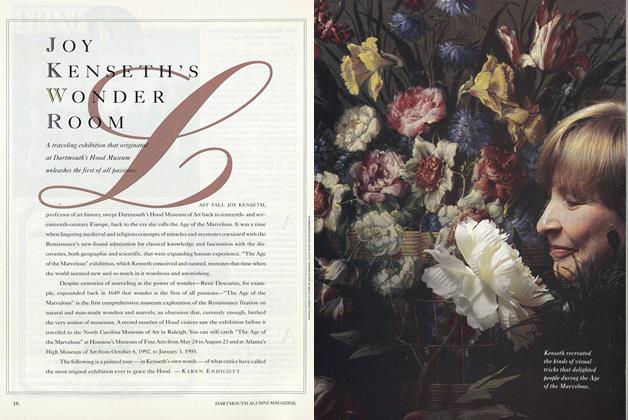

FeatureJoy Kenseth's Wonder Room

April 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

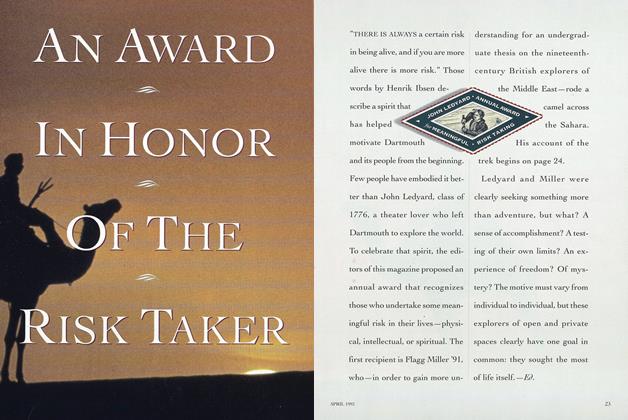

FeatureAn Award In Honor Of The Risk Taker

April 1992 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

April 1992 By "E. Wheelock"

Ulrike Rainer

Article

-

Article

ArticleARE THE COLLEGES OF TODAY SUFFICIENTLY HONORING THE CLAIMS OF SCHOLARSHIP?

OCTOBER, 1906 -

Article

ArticleD.C.A.C. Shows Surplus

October 1936 -

Article

ArticleAcademic Delegates

June 1953 -

Article

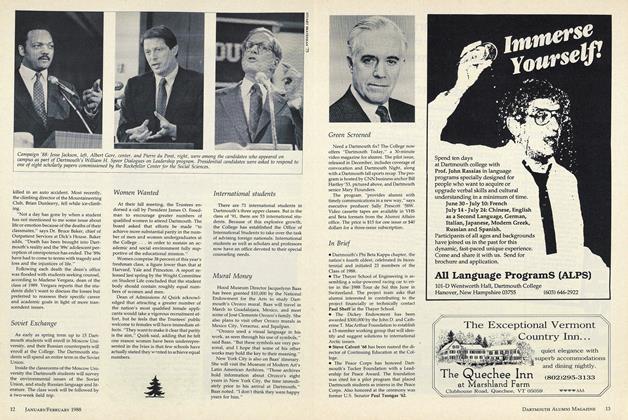

ArticleWomen Wanted

FEBRUARY • 1988 -

Article

ArticleA Student of the Eskimos

February 1960 By J.B.F. -

Article

ArticleFace To Watch

DECEMBER 1997 By James Zug '92