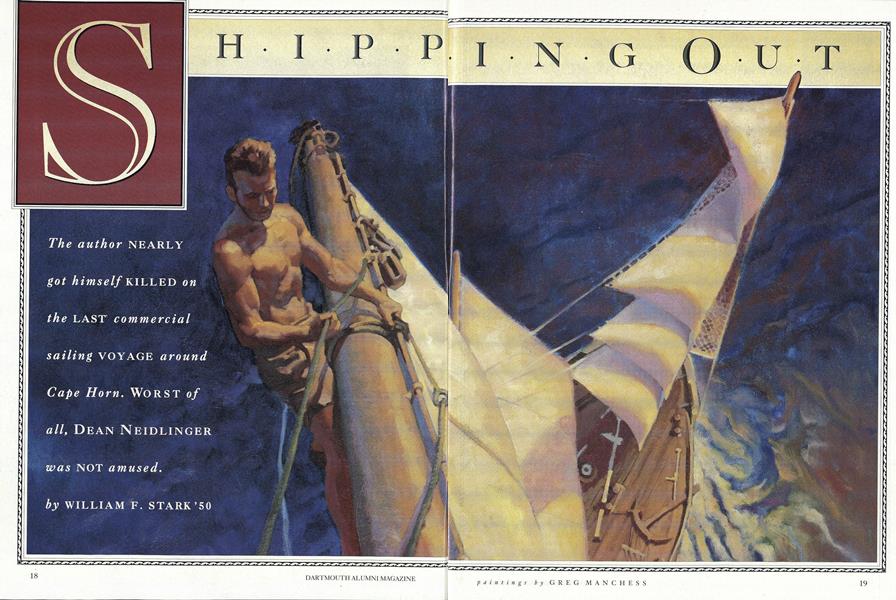

The author NEARLY got himself KILLED onthe LAST commercialsailing VOYAGE aroundCape Horn. WORST ofall, DEAN NEIDLINGER was NOT amused.

In June of 1949 my parents were UNPLEASANTLY SURPRISED toopen a letter addressed to me from DEAN of the College LLOYD "PUDGE" NEIDLINGER '23 that more or less THREATENED mewith EXPULSION. The dean—a BURLY former all-American FOOTBALL PLAYER who struck the FEAR OF GOD into a generation'sworth of WAYWARD Dartmouth students—wrote that he was "VERY SORRY" to learn that I had been a "DISTRACTING INFLUENCE" onother students during my BRIEF STINT in the junoor-year-abroad program in Zurich that fall. College officials would take a long hard look at my case before readmitting me to Dartmouth. The dean said he was sending the letter to my parents' home in Milwaukee with the hope that it would be forwarded: "I understand that you are probably enjoying a summer cruise on: a windjammer someplace between Australia and England..."

Never mind the charges; that bit about "enjoying a summer cruise" was all wrong. At the time Dean Neidlinger was writing his letter I was literally praying for my life as I clung by my fingertips from a lurching, ice-glazed yardarm 150 feet above the deck of a fourmasted Finnish bark off Cape Horn.

HAD QUIT THE STUDY ABROAD PROGRAM TO SIGN on the last cargo-carrying windjammer to sail from Australia to England. This "summer cruise" was in the world's roughest seas during the height of the Antarctic winter. The ship resembled a yacht only insofar as she carried a set of sails. She had no radio, no auxiliary power, no electricity. A coal-fired stove was for cooking, and the menu consisted largely of beans, porridge, and salt pork. We didn't see land for more than four months.

But maybe the dean's reaction shouldn't have surprised me. The relationship between a Dartmouth education and a love of adventure and the sea already had proven to be an uneasy one for me. I'd acquired my love of the sea, paradoxically, growing up on a lake in Wisconsin. Since my early childhood I had been in boats—sailboats, canoes, rowboats—and relished reading about the great era of sail. It was natural that the summer after I turned 16, when I became subject to a family rule that required one to find a summer job, I chose to go to sea.

That first summer I crewed, seasick, as a dishwasher on a Great Lakes ore carrier. The following year I was a deckhand on an Alaskan fishing boat, the result of which is that I can't eat salmon to this day. After two years' training as a navy pilot during World War II, I was discharged in July 1946 and entered Dartmouth that fall. Completing my freshman year in the spring of 1947, I signed aboard a Swedish freighter that had docked at Milwaukee, near my home. That summer marked my first experience crossing an ocean, my first trip to Europe, and my first near-brush with the Dartmouth administration.

The ship, a small freighter named the Ragneborg, crossed to Gothenburg, Sweden, in 28 days. It was a fairly rough passage and the heavy following seas often prevented me from performing my job, which was to chip the paint on deck. In the course of the voyage I befriended the third officer, who was my age and the only member of the Swedish crew who spoke English. As we anchored off Gothenburg I gazed out at the Swedish coast and remarked to him that I wanted to see something: of the country. He offered to help me jump ship.

This was no small thing for an officer to suggest. In the seaman's code of conduct jumping ship is equivalent to breaking a contract, for when you sign on a ship you are expected to work for the duration of the voyage. To complicate matters, I had no passport. The young Swedish officer thought central Sweden was the safest place in these circumstances; he bought me a train ticket, somehow arranged to have my seabag taken ashore, and whispered good luck to me in the total darkness as I slipped down the gangplank and into freedom and the kind of summer a young man dreams about.

MY SECOND DAY ON LAND I WAS TRYING to order an ice cream cone at a street fair and was stumbling over the word for "vanilla." when I was helped by a young woman who spoke English. Anne-Marie was 20 years old and could have passed for Ingrid .Bergman's younger sister. What's more, her parents were spending the summer in far-off northern Sweden. She and I spent a month hiking around the mountains and lakes of central Sweden.

Early on an August morning Anne-Marie and I finally said goodbye on the sun-drenched platform of the station of Orebro, her hometown. As the train pulled out and I waved from an open window, my deep feeling for her was repla.ced by one: of panic. The last days with Annie-Marie I had pushed the thought from my mind that I had to be back at Dartmouth in four short weeks. How would I get there? It wasn't the sort of thing I wanted to explain either to my father or Dean Neidlinger that I was late for the fall term because I'd jumped ship and spent the summer with a Swedish woman.

Seabag slung over my shoulder, I marched directly from the Gothenburg railroad station to the harbor, where at least a dozen ships were tied at the docks and another half-dozen anchored in midstream. I recognized one of the closer vessels to be an American Liberty Ship. I got a little taxi boat to ferry me out to the American ship.

The captain of the U.S.S. Booker T. Washington was a black man, tall and very thin. He signed me on as an oiler, one of six white men in the 40-man crew. That afternoon an officer took me below to the engine room and we descended a long series of ladders deep into the ship. Reaching bottom, wave after wave of hot air blew against me. Pistons pounded, wheels spun, and the grinding and grating of the engines, coupled with the intense heat, made me feel sick. My job was to crawl around on the pipes of the engine room and wrap them with burlap. Coming up on deck was like coming out into a cool, windswept paradise.

I minded my own business and no one paid much attention to me, although it seemed that everyone in the crew knew I belonged to "The University." Somehow, the rumor spread that I was in medical school. I must say I made no attempt to Correct the error. Soon I was referred to as "The Doctor."

About ten days out, a union meeting was held in the mess room. All in the crew, including me, belonged to the National Maritime Union. The purpose of the meeting was to elect a delegate to the national convention to be held the next month in Washington, D.C. Seemingly out of nowhere someone shouted, "Let's elect The Doctor." Before I could say anything, I was chosen unanimously to represent the Booker T. Washington. I hastily thanked the crew but declined, because I had to return to Dartmouth as soon as I set foot on shore. I regretted not being able to represent the ship then, and I still do.

After 19 days at sea we anchored off Norfolk, Virginia, and I headed north on the Boston & Maine Railroad for White River Junction, arriving with two days to spare—a triumph of impulsive navigation.

IT WAS DURING THE holiday break in the winter of 1948—my junior year abroad that I went skiing in Austria and met two young English naval officers. Of course, the talk turned to ships, and they told me they had recently seen a squarerigged sailing ship on the Thames in London. They said she was involved in the Australian grain trade.

I could not believe what they were saying. During grade school I had avidly read articles in National Geographic about the sailings of this little fleet from Australia to the U.K. via: the treacherous Gape Horn. Every year a ship or two was lost. By the beginning of World War II fewer than a dozen were in service. I was under the impression that not a single one of these square-riggers had survived the war. I made a few telephone calls and learned that the ship on the Thames was the Finnish bark Passat, on her way to Port Victoria, Australia, along with her sister ship, the Pamir. Both were to pick up cargoes of grain.

Within a week I had written Dean Neidlinger that I was quitting the study-abroad program. I sold my books, scraped up whatever money I could beg or borrow, and was in Rome, where I boarded a small plane carrying Italian farmers to Australia. Ten days later, after many stops and delays across Asia and India, we landed in Sydney. It wasn't until I'd reached Australia and there was no turning back—that I wrote my parents and told them what I had done.

I proceeded to Port Victoria, an isolated South Australian village, where I was told that both ships were to arrive in two or three weeks. Down to my last dollars, I took a job as a longshoreman. For the next two months I wrestled with 180-pound sacks of grain. The ships finally arrived under full sail, each carrying an acre of canvas, a sight indescribably beautiful.

Both ships had full crews.

My boss on the dock assigned me to help load the Pamir. Unloading the ship's ballast of sand and gravel and

then loading 60,000 bags of barley took more than a month. Three days before the job was finished, a brawl broke out in Port Victorias waterfront pub. Authorities sentenced three Pamir crew members to 90 days each in the Adelaide jail. I was signed on as an able-bodied seaman and joined the Pamir's 30-man crew of Australians, New Zealanders, and Finns. I was the only American aboard.

We set sail from Port Victoria in May 1949 bound for Falmouth, England, 16,000 nautical miles away. Thus began the world's last commercial Cape Horn voyage under sail, an event that helped mark the end of the sailing era. It was winter in the Southern Hemisphere, and we sailed toward Cape Horn. Soon we were plowing through heavy gray seas less than 600 miles from the Antarctic Circle. We were constantly wet, cold, and exhausted.

The work was unbelievably demanding. We spent much of the time aloft, taking in sail in the heavy winds, then letting it out as the winds diminished, only to take it in again. The tops of three of the Pamir's four masts were 168 feet above the deck. To get aloft, we climbed rope ladders made up of heavy vertical lines called shrouds, with smaller horizontal ropes serving as rungs, called ratlines. Upon reaching the yardarm (the horizontal spar to which the sail was fastened), we edged out on a cable foot-rope. With our feet balanced on this single cable, we pulled in the canvas and furled it to the yardarm, with nothing but a void and certain death below for the unwary. We worked for hours in these heights; I was amazed how quickly I had grown used to being aloft.

The Pamir was now well south, with raging Antarctic gales the norm. With only six hours of daylight in 24, we worked much of the time in the dark both aloft and on deck. There were many times when I desperately wished I'd never left home and college.

One night, not far off Cape Horn, the wind began to freshen rapidly. The mate blew the whistle and we stumbled onto a dark, heaving deck. He ordered three of us to take in the fore royals, the uppermost sails. With the wind clawing at our clothes, we climbed a rope ladder as high as a 14-story building. Below, the 316-foot ship performed like an acrobat. The three of us spent 15 or 20 minutes on the yardarm, furling canvas. We worked only a few feet apart, but it was so dark that we were barely visible to one another. The shrieking wind made it impossible to hear, and the masts thrashed around violently. It took a real effort to hold on.

Finished, we edged our way along the yardarm to the mast. I saw a line that still needed securing. The other two started climbing down. I followed a minute later. Meanwhile the temperature had plunged and I could feel a light icy glaze on parts of the shrouds. This was a new experience. As I descended I grasped the ropes as tightly as I could.

I was 150 feet above the deck when a terrific sea smashed into the ship. The mast gave a convulsive lurch. My feet were wrenched from the ratlines. I clung desperately to the icy ropes, my feet vainly seeking the ratlines in the black night. I knew it was only a matter of seconds before I would lose my grip and plummet through the dark Antarctic night. I remember exactly what I shouted into the wind: "Dear Lord, please help me get my body back on the ship."

Whether I imagined it or not, the ship seemed to make an unusual motion, almost the reverse of what had created my predicament. My right foot found a ratline. Ten minutes later I had climbed down to the ice-coated deck.

We rounded Cape Horn on July 11 and as we turned north the winds dropped, the seas subsided, and the temperature rose. We crossed the equator on August 5. On October 5. 1949, after almost five months at sea, the Pamir dropped anchor in Falmouth, England. Now came my next challenge: I had somehow to convince Dean Neidlinger and Dartmouth College to take me back into its fold.

My parents had opened the dean's letter to me. The letter so concerned my father that he asked his attorney and best friend Leroy Burliriganie. a former Rhodes Scholar, to draft a letter on his behalf to Dean Neidlinger. My father admitted in the letters that he felt somewhat responsible for my sudden decision to leave Zurich and sign on a windjammer, because many times he'd told me he wished he'd had the opportunity to travel the world when he was young.

Nevertheless my father wasn't very happy with the manner in which I had left the Zurich program, and Dean Neidlinger seemed much less so. I returned to Hanover in hopes of being* readmitted for the winter term. I was so nervous before my meeting with the dean that I could hardly speak, but much to my surprise he greeted me with a hearty handshake and the words, "Welcome back!"

THAT TRIP ON the Pamir, with all its difficulties, satisfied my longing to go to sea. I completed my studies and graduated the following. year. I joined my father in the family candymanufacturing business in Milwaukee, married, and had four children. The Pamir, meanwhile, was sold by her Finnish owners to the German government, who used her as the training ship for young cadets in the nation's merchant fleet. The Pamir was equipped with auxiliary power, radio, refrigeration, and heat. Her voyages were limited to the Atlantic. Seven years later she was caught in a hurricane off the Cape Verde Islands. Today the Pamir and her last crew of 80 lie at the bottom of the North Atlantic.

As for Anne-Marie, the Swedish woman, our correspondence tapered off a year or two after that summer and finally stopped altogether. Just two springs ago, however, the director of the Swedish Emigrant Museum called on my wife, Judy, arid me at our home on Wisconsin's Pine Lake. This beautiful lake, first settled in .the 1840s, was the earliest Swedish colony in America west of the Alleghenies. The Swede was visiting us because I had written extensively on that first group of settlers.

During Iris stay I mentioned the summer I spent with his flaxen-haired countrywoman.

"Should I try to get her address?" he asked.

"That was 42 years ago," I replied, "and I am sure she now has a married name."

"I bet I can get it. Give me two weeks."

Included in his thank you note a short time later was the address of Anne-Marie Dehmbeck, nee Porslund.

She was still living in Orebro.

In the fall of 1991 Judy, who is a landscape architect, and I were visiting Sweden. One day, while she Was tramping around Stockholm gardens with her Swedish counterparts, I was nervously boarding the Orebro train.

wondered if Anne-Marie would recognize me now. Back then my only clothes were navy dungarees plus a sweater and a white Dartmouth sweatshirt.

As the train neared Orebro, I began to think; this whole trip was stupid. I hadn't seen Anne-Marie for 42 years, hadn't written her for decades, hadn't even bothered to phone ahead.

I told the story to the taxi driver as we drove from the station to an attractive red bungalow nestled in a grove of pines.

He said, "I hope for your sake her husband isn't home."" He was. Anne-Marie's husband, Billy, answered the door. Blond, wiry, very tan, he was barefoot and wore yellow running shorts and a T-shirt. :

Down a long hall I recognized Anne-Marie's willowy: figure. She was just as blond and tan as Billy. Dressed in a red jogging suit, she too was barefoot: They were moving Furniture. She was speechless when she realized who I was.

On the other hand, Billy, who was in the shoe-leath.er business, was a nonstop talker. We chatted for an hour. Then, ten minutes before I left, Billy excused himself. As he came back around the hallway corner, he shouted, "Well, how do I look now?"

He bounced into the living room. In place of his T-shirt he proudly wore my 42-year-old Dartmouth sweatshirt.

"PUDGE" NEIDLINGER thought STARK had ABSCONDED to go Oil a SUMMER CRUISE.

ANNE-MARIE knew the WORD for vanilla. They LOST touch for 42 years.

I Clung to the Icy Ropes, my feet Vainly Seeking the ratlines inthe Dark Night.

WILLIAM STARK is the author of seven books, including: Wisconsin, River of History; Along die Black Hawk Trail; and Ghost Towns of Wisconsin.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureRobert Christgau's Ear Turns '51

April 1993 By BILL GIFFORD '88 -

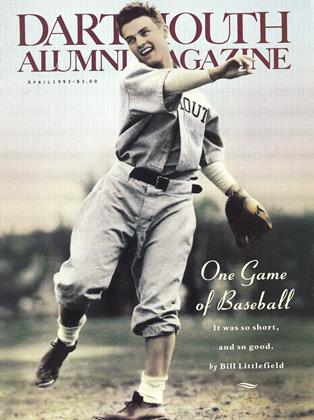

Cover Story

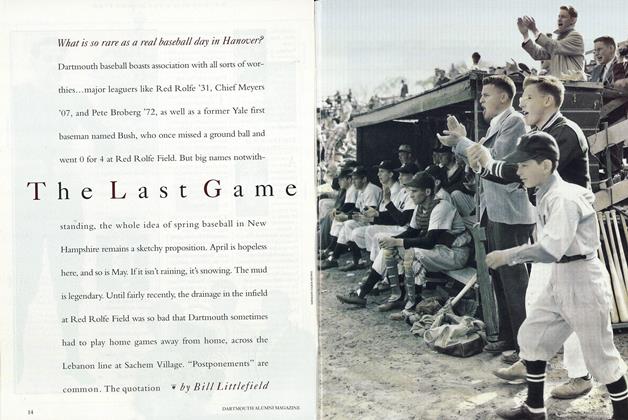

Cover StoryThe Last Game

April 1993 By Bill Littlefield -

Feature

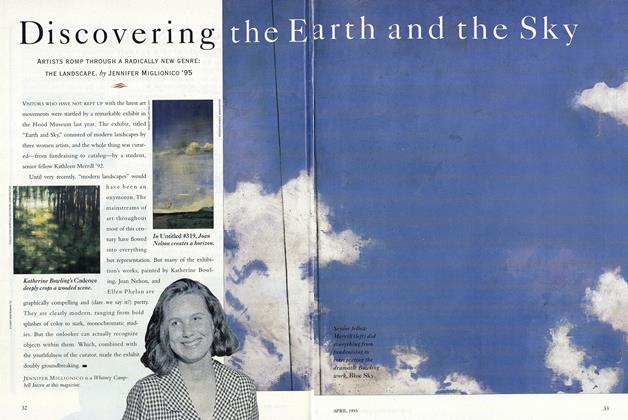

FeatureDiscovering the Earth and the Sky

April 1993 By Jennifer Miglionico '95 -

Article

ArticleSchools for the Twenty-First Century

April 1993 By Professor Faith Dunne -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

April 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleNothing Less Than a Hero

April 1993 By James O. Freedman

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWhat We Do Best

December 1994 -

Feature

FeatureAlbert I. Dickerson '30 1908-1972

JULY 1972 By C.E.W. -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMariam Malik '98

OCTOBER 1997 By Deborah Solomon -

Feature

FeatureThe STREAMLINER DINER

APRIL 1998 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GET YOUR NAME INTO THE GUINNESS BOOK OF WORLD RECORDS

Jan/Feb 2009 By LARRY OLMSTED, MALS '06 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRousseau Cops an Exam

MARCH 1995 By Philippa M. Guthrie '82