THE STUDENTS SIT nervous and uncomfortable, awaiting the beginning of the first day of class. As they scan the cramped basement room, the distractions overwhelm them. On one side they hear the muffled staccato of distant gunshots while on the other comes the continuous drone of static and the routine communications of a police radio. The lights in the classroom are dim and a draft enters through an open window in the rear. As the last few students shuffle in, they take their place on the floor; there aren't enough chairs for the over-enrolled class. A radio in the front of the room is playing, and one student shuts it off as he ambles in. "Did I say you could turn off the radio?" demands the teacher. The music resumes, and the confused student takes his seat on the floor.

Is this really Dartmouth? Yes, surprisingly enough, it is. This is Professor Robert Binswanger's Ed 36: Urban Education.

According to Professor Binswanger's method, you can't teach students about urban education while they're still surrounded by the comforts of the peaceful Dartmouth campus. He moved his class to the basement of Silsby Hall in an attempt to recreate a more realistic inner-city environment. In addition to learning about the difficulties facing teachers and administrators in urban settings, students are exposed to the problems first-hand both at Dartmouth and in a field trip to Boston's city schools.

Binswanger, a former headmaster of Boston Latin and a nationally recognized expert in education policy, had groups of his students work with real problems currently facing school districts and then present solutions to a panel of judges. "Urban Education was not only a class but an experience," noted Alison Mountz '95. "Real situations are the best way to transform some of the abstract concepts of academia into real-life application."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

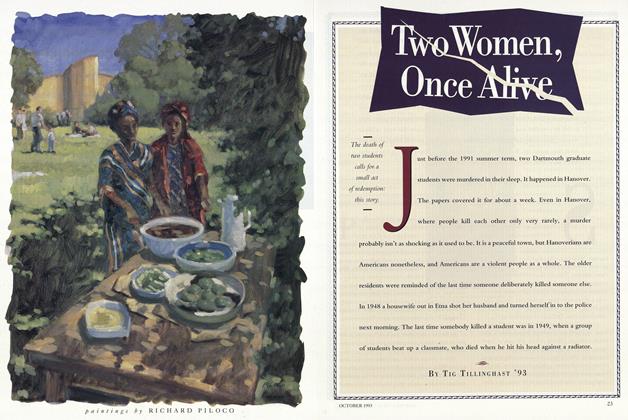

FeatureTwo Women, Once Alive

October 1993 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

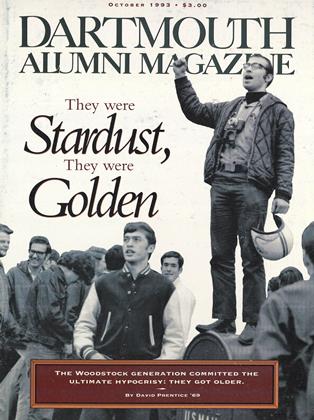

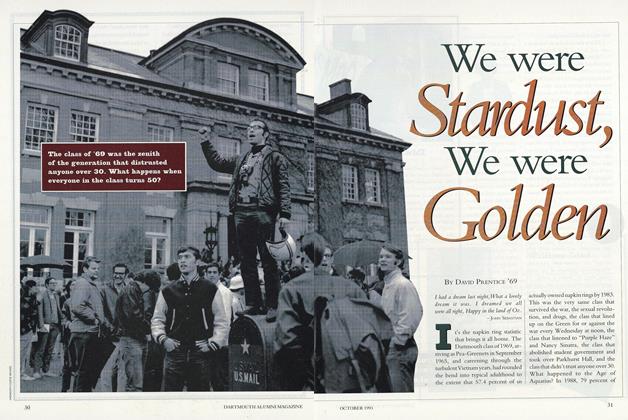

Cover Story

Cover StoryWe were Stardust, We were Golden

October 1993 By David Prentice '69 -

Feature

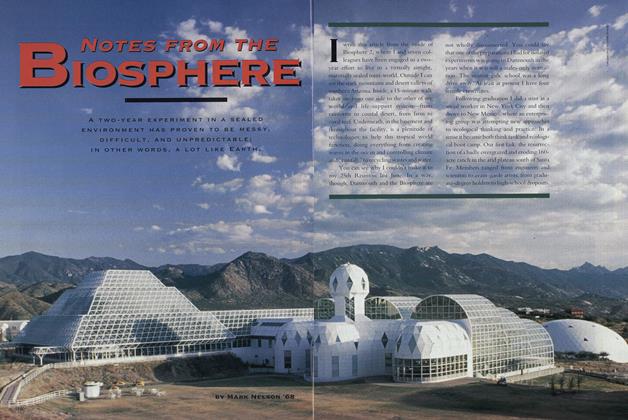

FeatureNotes from the Biosphere

October 1993 By Mark Nelson '68 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

October 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleThe Daughters of Eve

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

October 1993 By Thomas G. Jackson

Kai Singer '95

Article

-

Article

ArticleIcelandic Exchange

February 1953 -

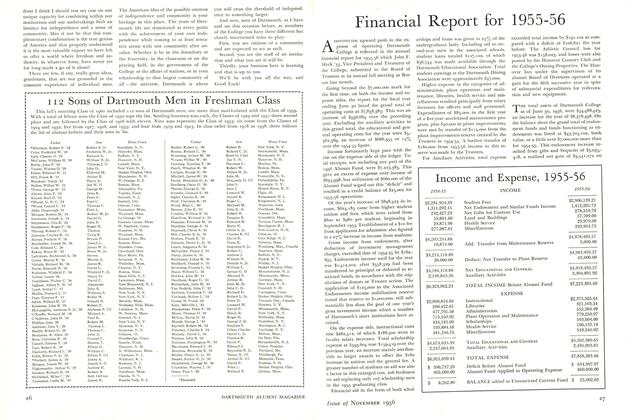

Article

ArticleII2 Sons of Dartmouth Men in Freshman Gláss

November 1956 -

Article

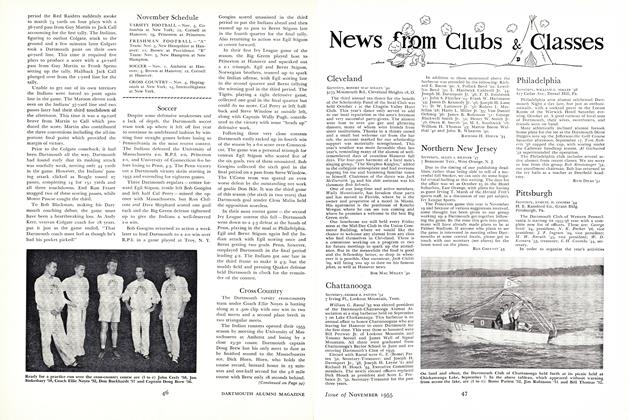

ArticleCross Country

November 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Article

ArticleSPORTS SCHEDULE

MAY 1963 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleTHE PRESENT ATHLETIC SITUATION

November 1921 By HORACE G. PENDER '97 -

Article

ArticleSAMUEL PENNIMAN LEEDS

June, 1910 By William Jewett Tucker