I had a dream last night, What a lovelydream it was. I dreamed we allwere all right, Happy in the land of Oz. -JOHN SEBASTIAN

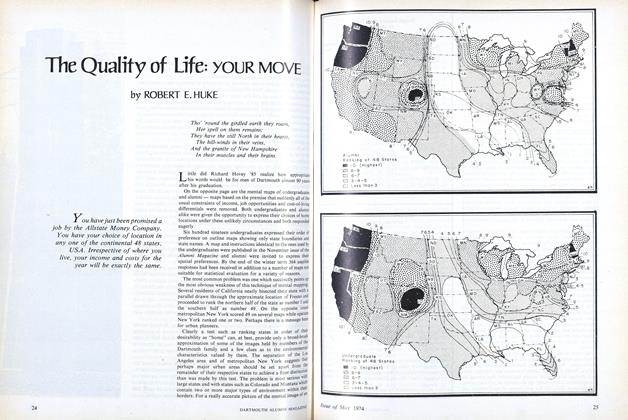

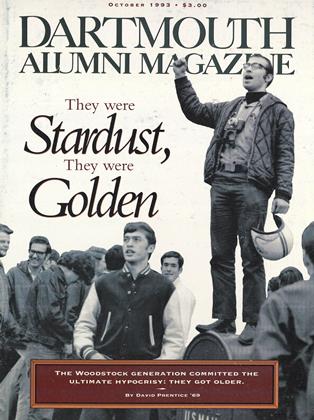

It's the napkin ring statistic that brings it all home. The Dartmouth class of 1969, arriving as Pea-Greeners in September 1965, and careening through the turbulent Vietnam years, had rounded the bend into typical adulthood to the extent that 57.4 percent of us actually owned napkin rings by 1983. This was the very same class that survived the war, the sexual revolution, and drugs, the class that lined up on the Green for or against the war every "Wednesday at noon, the class that listened to "Purple Haze" and Nancy Sinatra, the class that abolished student government and took over Parkhurst Hall, and the class that didn't trust anyone over 30. What happened to the Age of Aquarius? In 1988, 79 percent of '69s had a retirement plan.

This is the class that in less than a year will hold its 25th Reunion.

How do we know these numerical tidbits? For our early-15th Reunionin 1983,1 had decided it would be interesting to survey the class and present the results at the class dinner and later in my 1969 Newsletter. It seemed like a good way to find out a little more about ourselves. I put together an absurdly long form and printed it in an entire issue of The '69 Times. The response was so good that I repeated the effort in 1988, and I am gearing up to do it again for our 25th Reunion next year. You can get the news on the green cards, but it you really want to learn what people are thinking, you have to do a little digging. You go for some light frothy stuff, then you stick in some doozies to find out what's on people's minds.

(86 percent), and some took jobs that can best be described as "It's a living" or worse (10 percent). Twenty-one percent of us work more than 60 hours a week, 74 percent take the car to work, and the average salary in 1988 was $115,996—the class's total personal income amounts to $92,448,812 (think what a 1969 commune could accomplish). We have accumulated a goodly list of consumer goods, and our collective Least Commonly Owned items (chosen from my list) include a windmill (only two of us have one), a vibrating chair, a recreational vehicle, a poodle, and a bidet. Our Top Ten list of items owned includes a suit, a stereo, at least 50 books visible on shelves, and that retirement plan. Rather typical of any class our age.

And, as a class, we did start out normally. My father took pictures of me with my new friends in the class of 1969 during our Freshman Week. We must have looked like every class before us, including his own class of 1936. Over the next few weeks, we counted up to 69, we built bonfires, we had our beanies stolen, we won the tug-of-war and knotted up traffic, we did all those things that freshmen do. We had spirit and a healthy level of solidarity. We showed the upperclassmen, especially those '68s, that we were made of good stuff. When things went well, which they pretty much did at first, in Dartmouth slang we said we were golden.

Over the next four years, though, we began to derail. Was it sex, drugs, rock and roll, or the war? All of the above, but probably the war, mostly. Art Spiegelman, writing in The New Yorker, claims it was Mad Magazine that was the most subversive element—more than drugs, more than the war. Whatever it was, it's still with us.

For underneath the cameras costing more than $75 (#5 on that list of things we own), the two or more power tools (#7), and the dying plant (#14), there lies the feeling that things are not right. Something we had discovered in our student days, some- thing that had consumed many of us, has been lost in the riptide of years between then and now. In 1983, I asked what we gained—or lost by being at College during the late sixties. One of my classmates wrote, "we gained a feeling of being united in working towards a less materialistic, more caring world, but I've since lost some of that feeling.'

He is not alone. While both surveys showed that many enjo9y their jobs and their lives immensely, among our preidents and executive VPs and profes- sors, and others with lesser titles, there were indications of a sigmificant, growing restlessness .As the 25th Reunion approaches,as mi-life crisesdemand to be reckoned with, as the kids grow up, and indeed as we ourselves grow up, even the most cursory self evaluation brings up the idealism of 1969. What did we learn from those times, and what is it doing to us now?

"The Sixties gave us a broad perspective and a sense of skepticisin which I find healthy."

"We gained af sense of the power of idealism."

"We lost a period of tranquillity in which to work out those last years of adolescence. The unrest of those times profoundly affected most of our lives and has lett very lasting `hanges. But we gained in the long run by having to take a more critical look at the past and our futures."

"Gained a sense of personal and intellectual adventure. Lost the discipline necessary to really utilize the freedom to constructive ends."

"Times of crisis are always times of opportunity. Whether we responded or not depends on each of us individually."

"The social unrest made each of us confront who we were and where we were going. We learned to ask questions and not take things at face value. We learned the meaning of loyalty, friendship, and credibility. I hope we gained a sense of priorities.

It seemed so easy at the time: All we had to do was to work together, look out for each other, stand up tor what we believed in, and be counted, and we could change the world. For a group that grew up on 1950s television, it was right out of Davy Crockett's philosophy: "Be sure you're right, then go ahead." Once we were safe at last in the wide, wide world, though, it did not take too long for it to register that the world was too big, the problems too many, institutions too slow, and other avenues just too limited for much to be accomplished. Besides, there were families to raise, homes to pay for, resumes to revise, and, before too long, even that retirement to plan.

"We were Stardust, we were golden," Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young sang of the Woodstock generation, "and we got to get ourselves back to the garden." But there was no garden to get back to, just little suburban plots of veggies and roses to tend. What's wrong with this picture? The whole premise of the late sixties was youth. Peter Pan could stay young forever, but jimi and Janis held on only by removing themselves from time. They are both still 27. The rest of us broke our own cardinal rule: we grew old—and the whole paradox of our era came crashing down around us. Maybe it was Jerry Rubin who screwed us all up. By turning 30, just by living, we became hypocrites.

"I have relaxed my expectations, most likely to rationalize reality."

State. The unity, the enthusiasm, and the tireless dedication transformed Dartmouth and many in the Valley into a community which now seems sadly unreal. Today I find that people who were not in college then have little conception of what it was really like; among younger people, there is amazement that it could actually have happened. Are the fires nearly out? Like one classmate, I am afraid that many of us have come to feel "an inability to accept the likelihood that our presence for 35-80 years will have little or no effect on anything."

"To retain sanity, you simply change your expectations."

A classmate at our 1983 reunion seminar brought up an interesting concept: that most members of the class were on trajectories, those paths, like cross-country ski tracks, that were directing us on life and career paths, despite all our collegiate expectations to the contrary. Notwith- standing the fact that many of us liked our jobs, it was proving to be difficult for economic and perhaps even social reasons to get off the trajectory in order to go and clean up the world.

Write a question for this questionnaire: "Do you feel you have done anything to help the world?"

Now answer it: "Not yet."

What if you removed the pressure to bring in a salary? I asked classmates in 1983 and 1988 what they would prefer to be doing if salary were not an issue. Responses tended to center around golf, fishing, sports, hobbies, travel, reading, and writing—or coaching first base for the L.A. Dodgers. Aside from some "teaching" and medical-re- search replies, only three persons gave a specific "sixties" response: "job training for the hard-core unemployed," "running a non-profit group," and "spending more time with charitable/community work." Does all this mean that the class of 1969 has given up on those ideals that so permeated it in the late sixties and early seventies?

"If I am to change the world, or to make some tangible, worthwhile contribution, it must begin here—with myself, my family, my professional life, my community."

The ideals remained, but the scope had to narrow. If we were not going to change the world, the next best strategy was, inevitably, to channel one's energies into making the local environment as responsive, as safe, and as egalitarian as possible.

Most '69s have become involved in a wide variety of civic activities and concerns; the largest group is what I call "Kid/Youthoriented." Behind this group are the "Municipal" group and a widely varied "Miscellaneous" group that is mostly churchoriented. There is a single classmate involved in a peace group, another working for gun control, and one citizen who wants everyone to know that he "votes regularly."

"Economically I'm better off than I'd expected; in terms of having an effect on the world at large, I simply haven't and that's a disappointment."

I think a lot of '69s are carrying on a lingering feeling of unfulfilled obligation to something. We are living lives like everyone else, but we are feeling bad about it. True, we've done a terrific job with our families and we have been responsible in our careers and community life, but besides "voting regularly," we have not had the same sense of involvement and power as we felt in the years around 1969. Solutions are not as easy as we might have thought then—or are they?—and it's not as easy to rally our fellow citizens—our classmates—as it once seemed. It's as if the whole Zeitgeist changed as soon as we walked off campus for the last time. All of those vistas that we saw could never have been fulfilled; one of my friends wrote that we were on the crest of a wave that never broke. We moved on, we sold out, we joined the Establishment—and, over the last 15 years or so, banished that word from our vocabulary. But we have not forgotten.

"I care about whether we blow ourselves up, starving children in Africa, corrupt dictatorships in Central America, Mother Theresa, my children, Cathy, doing a decent job unencumbered by idiocy, staying alive, doing things I find pleasure in, saving the whales, keeping my car running, getting a farm, sharing the wealth, God, staying healthy, knowing how much is enough, making my part of the world a decent place to live. Everything else is worth giving up."

The class of 1969 was and is still a disparate group. True, there were segments of various degrees of unanimity on campus—groups who supported the war, or peace, or drugs, or beer, or the house, or getting a 5.0 grade-point average. Involvement and commitment to the subgroups, and possibly even to Dartmouth itself, seem to have superseded an affinity with the class. 1969 is too big, too amorphous to have any real meaning for many, and we still have a large number of '69s who have virtually no involvement with the class, though some still return to Hanover. The silent majority still is silent, and still is, sadly, perhaps a majority, though it may not once have been Nixon's silent majority.

Over the years, though, the situation has improved markedly, and the prospect for our 25th Reunion, in both Alumni Fund giving and early interest in the reunion itself, is most encouraging. Word is slowly getting out that reunions are not what they used to be. No longer a non-stop party, they are a time for some sharing, some bridge-building, and some reflection. I just received a letter that says it all.

"Dartmouth has really become an important part of my life—more so than I ever imagined when we were there. It was a unique time and place which cannot be duplicated. I found that at our last reunion the differences which seemed so marked 20 years before had blurred and softened, and that we had somehow become similar in many ways."

We may yet find our way back to the garden.

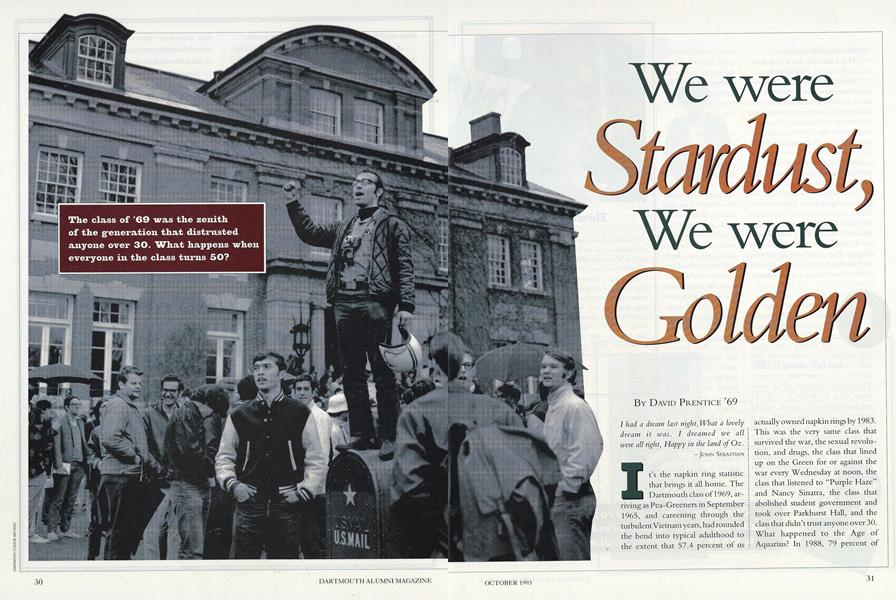

The class of '69 was the zenithof the generation that distrustedanyone over 30. What happens wheneveryone in the class turns 50?

The author in plaid poses with newfound friends in more innocent times.

One of my friends wrotethat we were on the crest ofa wave that never broke.

We moved on, we sold out,we joined the Establishment—and, over the last 15 yearsor so, banished that word fromour vocabulary.

DAVID L. PRENTICE fled New York andToronto for Pembroke, Ontario, where heis a partner in a marketing and graphicarts consultancy. He tends a small gardenat home and watches golden sunsets fromhis cabin on the Ottawa River.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

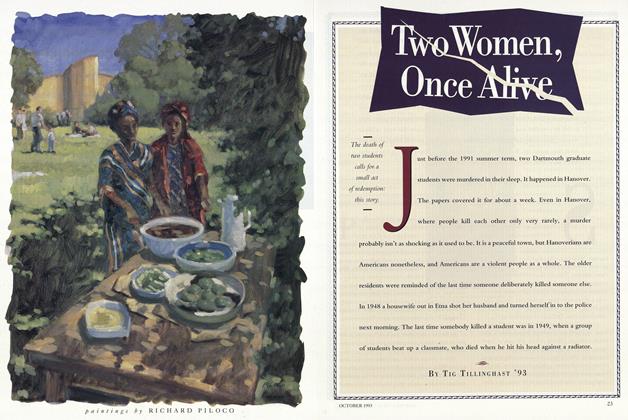

FeatureTwo Women, Once Alive

October 1993 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Feature

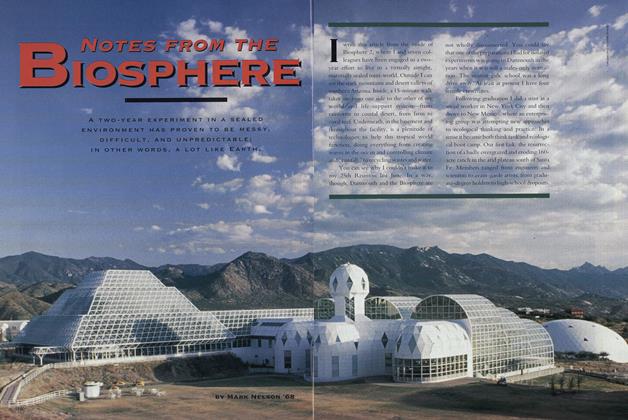

FeatureNotes from the Biosphere

October 1993 By Mark Nelson '68 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

October 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleThe Daughters of Eve

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

October 1993 By Thomas G. Jackson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

October 1993 By Amy Iorio