EVER WONDER WHO EVE'S DAUGH ters were? The Bible tells us that Cain, Abel, and Seth were Eve's sons. It tells that Cain had a wife (his sister?); that Cain's sons had wives (somehow there were women on the scene), and that Adam, husband of Eve, begat sons and daughters in the 930 years he lived. But we still don't know who the daughters werenor, for that matter, how long Eve, mother of all, lived.

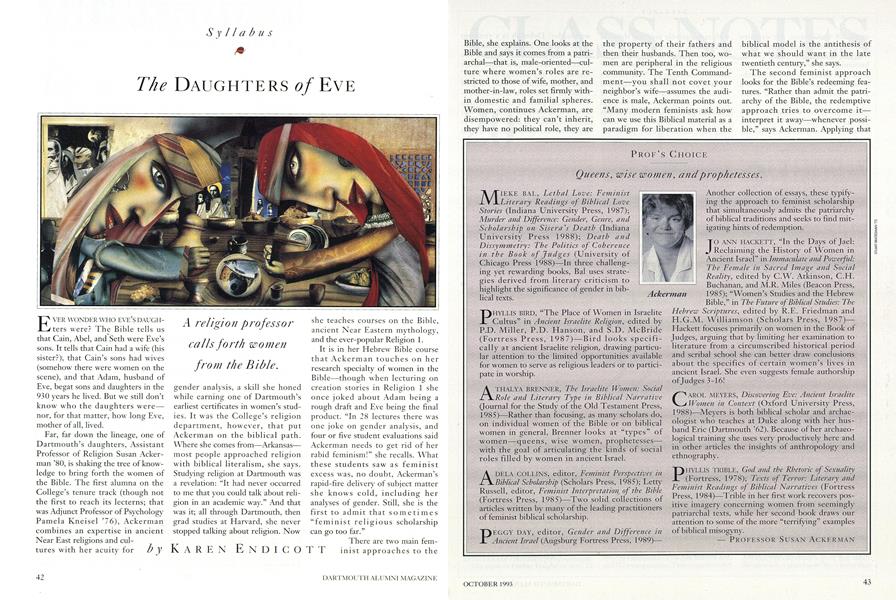

Far, far down the lineage, one of Dartmouth's daughters, Assistant Professor of Religion Susan Ackerman '80, is shaking the tree of knowledge to bring forth the women of the Bible. The first alumna on the College's tenure track (though not the first to reach its lecterns; that was Adjunct Professor of Psychology Pamela Kneisel '76), Ackerman combines an expertise in ancient Near East religions and cultures with her acuity for gender analysis, a skill she honed while earning one of Dartmouth's earliest certificates in women's studies. It was the College's religion department, however, that put Ackerman on the biblical path. Where she comes from—Arkansasmost people approached religion with biblical literalism, she says. Studying religion at Dartmouth was a revelation: "It had never occurred to me that you could talk about religion in an academic way." And that was it; all through Dartmouth, then grad studies at Harvard, she never stopped talking about religion. Now she teaches courses on the Bible, ancient Near Eastern mythology, and the ever-popular Religion 1. It is in her Hebrew Bible course that Ackerman touches on her research specialty of women in the Bible—though when lecturing on creation stories in Religion 1 she once joked about Adam being a rough draft and Eve being the final product. "In 28 lectures there was one joke on gender analysis, and four or five student evaluations said Ackerman needs to get rid of her rabid feminism!" she recalls. What these students saw as feminist excess was, no doubt, Ackerman's rapid-fire delivery of subject matter she knows cold, including her analyses of gender. Still, she is the first to admit that sometimes "feminist religious scholarship can go too far."

There are two main feminist approaches to the Bible, she explains. One looks at the Bible and says it comes from a patriarchal—that is, male-oriented—culture where women's roles are re- stricted to those of wife, mother, and mother-in-law, roles set firmly within domestic and familial spheres. Women, continues Ackerman, are disempowered: they can't inherit, they have no political role, they are the property of their fathers and then their husbands. Then too, women are peripheral in the religious community. The Tenth Command ment—you shall not covet your neighbor's wife—assumes the audience is male, Ackerman points out. "Many modern feminists ask how can we use this Biblical material as a paradigm for liberation when the biblical model is the antithesis of what we should want in the late twentieth century," she says.

The second feminist approach looks for the Bible's redeeming features. "Rather than admit the patriarchy of the Bible, the redemptive approach tries to overcome it— interpret it away—whenever possible," says Ackerman. Applying that approach to Genesis, she explains that the Hebrew term "adam" refers initially to humanity. "God created humanity—or an 'earthling.' Only after God takes a rib from this earthling do the genders—Adam and Eve exist." Now here's the redemptionists' punchline: Even though the curses of Genesis 2 and 3 proclaim that man shall be dominant over women, this occurred after the Fall; God's original intent was that women and men are equal. Thus, to live in harmony with God's original intent, the sexes would be equal.

Ackerman finds herself halfway between these two feminist perspectives. "I am willing to admit the Bible's patriarchy," she says, "and I don't have a theoretical stake in making every biblical text look 'egalitarian.' Yet I do think there are texts, often overlooked, that suggest some redemptive possibilities."

For example, there's the story of Deborah, the woman who was both prophet and warrior. Not content with redemptively pointing this out, Ackerman wants to know why Deborah appears in roles the Bible otherwise reserves for men. For answers she turns to Near Eastern mythology. Ancient Israel emerged out of the Near Eastern tradition of polytheism, replete with powerful gods and goddesses. As the Israelites adopted monotheism, they never fully rejected the ancient pantheon. Rather, in a process of demythologizing and historicizing, they took the gods and goddesses out of the divine realm and brought them into the human world. Ackerman contends that the story of Deborah is just such a Biblical reworking of a mythical war goddess: "While ostensibly the battle in which Deborah fights looks like a human territorial squabble, it in fact is a holy war with divine elements—the stars fight from the heavens, rainstorms sweep the Canaanites away. This divine element explains for me the incongruity of having a woman war leader. Deborah is a remnant of the older mythologies about Canaanite war goddesses." Would the Israelites have known these older Canaanite mythologies? "Yes," Ackerman replies. "The song of Deborah dates from around 1200- 1150 BCE [before the Christian Era] when Canaanite culture was alive and well. But none of this is to say Deborah really existed. It's all myth and legend."

This is Ackerman's kind of analysis. She has just published a similar argument about "The Queen Mother and the Cult in Ancient Israel" in the staid Journal of Biblical Literature. It was the mother of the ancient Canaanite king Sisera who prompted Ackerman's research on queen mothers. Not only is Sisera's mother nameless, there is precious little information about her. Sounds a bit like Eve's daughters. Perhaps there is nothing new under the sun. Then again, Ackerman's work is not yet finished. MI

A religion professorcalls forth womenfrom the Bible.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTwo Women, Once Alive

October 1993 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

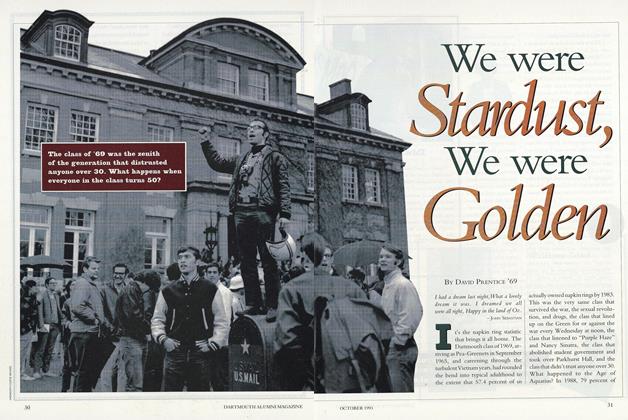

Cover Story

Cover StoryWe were Stardust, We were Golden

October 1993 By David Prentice '69 -

Feature

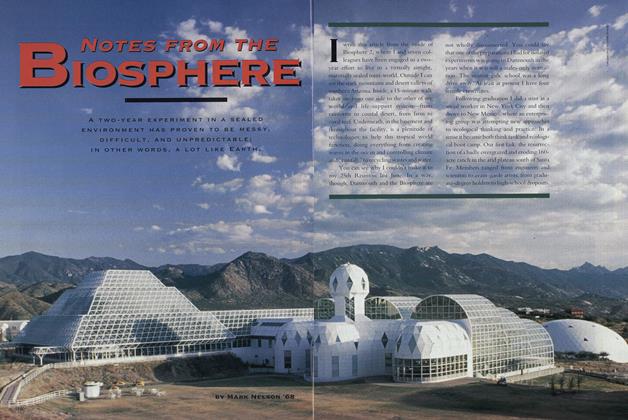

FeatureNotes from the Biosphere

October 1993 By Mark Nelson '68 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

October 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

October 1993 By Thomas G. Jackson -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

October 1993 By Amy Iorio

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleHold that Curriculum

June 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticlePatient Talk

September 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleGrade Deflators

SEPTEMBER 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleVirtual Munchausen

DECEMBER 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Article

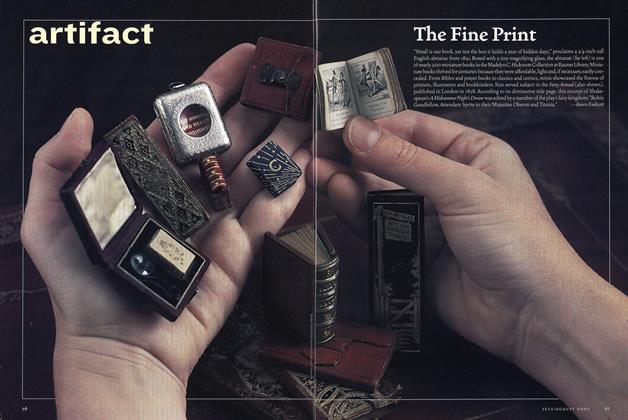

ArticleThe Fine Print

July/Aug 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWHEN POETRY SPEAKS

FEBRUARY 1991 By Professor Cleopatra Mathis, Karen Endicott

Article

-

Article

ArticleCRITICISM OF MAGAZINE

March, 1909 -

Article

ArticleMEETING OF TRUSTEES

June, 1915 -

Article

ArticleDR. F. P. LORD STUDYING RURAL DISTRICTS OF STATE

December 1921 -

Article

ArticleMR. BRYAN INTERVIEWED BY UNDERGRADUATES

January 1924 -

Article

ArticleHighest Award of the College

FEBRUARY, 1928 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth 42, Columbia 0

DECEMBER 1962 By DAVE ORR '57