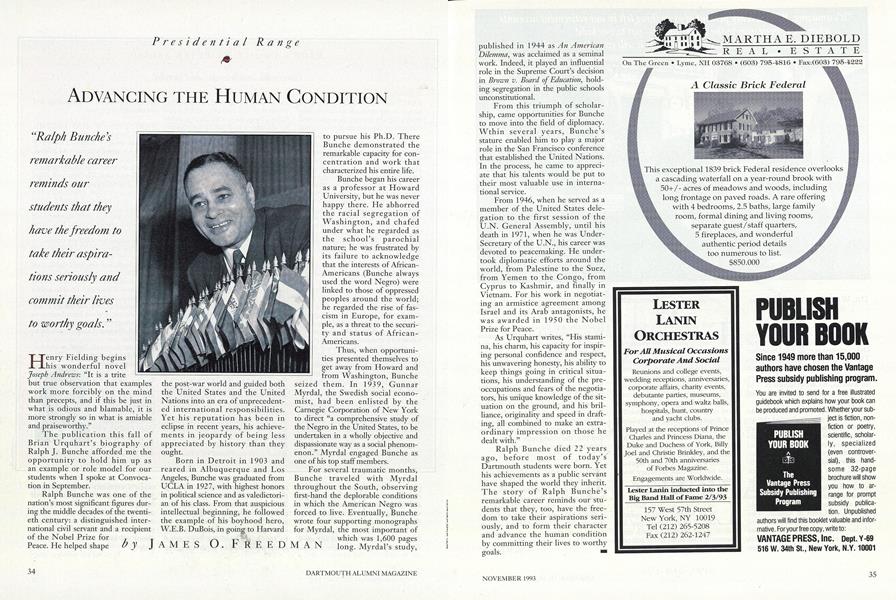

"Ralph Bundle'sremarkable careerreminds ourstudents that theyhave the freedom totake their aspirations seriously andcommit their livesto worthy goals."

Henry Fielding begins his wonderful novel Joseph Andrews: "It is a trite but true observation that examples work more forcibly on the mind than precepts, and if this be just in what is odious and blamable, it is more strongly so in what is amiable and praiseworthy."

The publication this fall of Brian Urquhart's biography of Ralph J. Bunche afforded me the opportunity to hold him up as an example or role model for our students when I spoke at Convocation in September.

Ralph Bunche was one of the nation's most significant figures during the middle decades of the twentieth century: a distinguished international civil servant and a recipient of the Nobel Prize for Peace. He helped shape the post-war world and guided both the United States and the United Nations into an era of unprecedented international responsibilities. Yet his reputation has been in eclipse in recent years, his achievements in jeopardy of being less appreciated by history than they ought.

Born in Detroit in 1903 and reared in Albuquerque and Los Angeles, Bunche was graduated from UCLA in 1927, with highest honors in political science and as valedictorian of his class. From that auspicious intellectual beginning, he followed the example of his boyhood hero, W.E.B. DuBois, in going to Harvard to pursue his Ph.D. There Bunche demonstrated the remarkable capacity for concentration and work that characterized his entire life.

Bunche began his career as a professor at Howard University, but he was never happy there. He abhorred the racial segregation of Washington, and chafed under what he regarded as the school's parochial nature; he was frustrated by its failure to acknowledge that the interests of African-Americans (Bunche always used the word Negro) were linked to those of oppressed peoples around the world; he regarded the rise of fascism in Europe, for example, as a threat to the security and status of African-Americans.

Thus, when opportunities presented themselves to get away from Howard and from Washington, Bunche seized them. In 1939, Gunnar Myrdal, the Swedish social economist, had been enlisted by the Carnegie Corporation of New York to direct "a comprehensive study of the Negro in the United States, to be undertaken in a wholly objective and dispassionate way as a social phenomenon." Myrdal engaged Bunche as one of his top staff members.

For several traumatic months, Bunche traveled with Myrdal throughout the South, observing first-hand the deplorable conditions in which the American Negro was forced to live. Eventually, Bunche wrote four supporting monographs for Myrdal, the most important of which was 1,600 pages long. Myrdal's study, published in 1944 as An AmericanDilemma, was acclaimed as a seminal work. Indeed, it played an influential role in the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education, holding segregation in the public schools unconstitutional.

From this triumph of scholarship, came opportunities for Bunche to move into the field of diplomacy. Wthin several years, Bunche's stature enabled him to play a major role in the San Francisco conference that established the United Nations. In the process, he came to appreciate that his talents would be put to their most valuable use in international service.

From 1946, when he served as a member of the United States delegation to the first session of the U.N. General Assembly, until his death in 1971, when he was UnderSecretary of the U.N., his career was devoted to peacemaking. He undertook diplomatic efforts around the world, from Palestine to the Suez, from Yemen to the Congo, from Cyprus to Kashmir, and finally in Vietnam. For his work in negotiating an armistice agreement among Israel and its Arab antagonists, he was awarded in 1950 the Nobel Prize for Peace.

As Urquhart writes, "His stamina, his charm, his capacity for inspiring personal confidence and respect, his unwavering honesty, his ability to keep things going in critical situations, his understanding of the preoccupations and fears of the negotiators, his unique knowledge of the situation on the ground, and his brilliance, originality and speed in drafting, all combined to make an extraordinary impression on those he dealt with."

Ralph Bunche died 22 years ago, before most of today's' Dartmouth students were born. Yet his achievements as a public servant have shaped the world they inherit. The story of Ralph Bunche's remarkable career reminds our students that they, too, have the freedom to take their aspirations seriously, and to form their character and advance the human condition by committing their lives to worthy goals.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

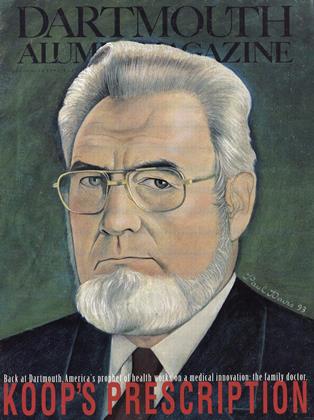

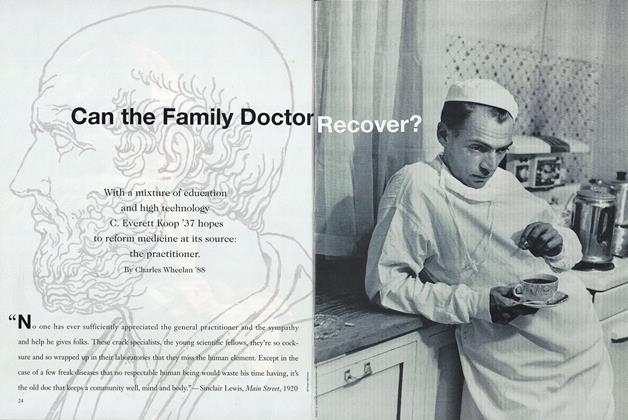

Cover StoryCan the Family Doctor Recover?

November 1993 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureTHE OLD MEN AND KC

November 1993 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

FeatureProphet of Limits

November 1993 By Suzanne Spencer '93 -

Feature

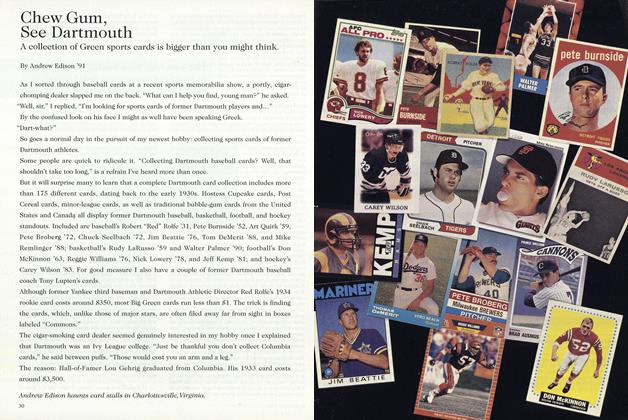

FeatureChew Gum, See Dartmouth

November 1993 By Andrew Edison '91 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

November 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

November 1993 By William Blake, W. Blake Winchell

James O. Freedman

-

Article

ArticleTHE TRANSFORMING POWER OF LANGUAGE

SEPTEMBER 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Human Scale

September 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Idealist a Leader

February 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWhat the Soul Asks

SEPTEMBER 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWomen and Men of Dartmouth

OCTOBER 1997 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Uncertain Future of Medical Education

DECEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman