"Thurgood Marshall allied his formidable talents with an idea whose time had not merely come but was long overdue."

AN HOUR AFTER I FINISHED writing a review for the Boston Globe of Carl T. Rowan's biography of Justice Thur good Marshall, Dream Makers, DreamBreakers (Little, Brown), I received the call that I had long dreaded, informing me that Thurgood Marshall had died.

His was one of the great American stories. Born in Baltimore in 1908, the great-grandson of a slave, he became one of the most important public lawyers of the century (only Louis D. Brandeis belongs in his class) and the first AfricanAmerican to serve as a justice of the United States Supreme Court. From the very beginning, Marshall faced racial discrimination. Rebuffed in his efforts to attend the all-white University of Maryland Law School, he was forced to commute for three years to Howard Law School in Washington. There he met the most important mentor of his life, Dean Charles Hamilton Houston, who impressed upon him the necessity of craftsmanship and the obligation of fighting against segregation, and who later recruited him to the legal staff of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. During his years of service with the NAACP, Marshall allied his formidable talents with an idea whose time had not merely come but was long overdue. Carefully, he laid down the incremental strategy for the assault on the citadel of segregation an assault that culminated in the Supreme Court's 1954 decision in Brown v. Board ofEducation, holding segregation in the public schools unconstitutional. That decision renewed this country's commitment to equality.

Had his career ended at that point, Marshall would have earned an important place in American history. But he went on to serve with distinction as a federal appellate judge and as Solicitor General of the United States. When President Lyndon Johnson appointed Marshall to the Supreme Court in 1967, the President said, "I believe it is the right thing to do, the right time to do it, the right man, and the right place." Marshall carved out a special place on the Court its most articulate and persistent defender of the constitutional rights of minorities, women, criminal defendants, and the poor.

Journalist Carl Rowan had known and admired Justice Marshall for decades. His is not the first biography of Marshall, but it is the most substantial to date. It adds to our understanding of Marshall's life by drawing upon previously unpublished records of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and upon extensive and candid interviews with Marshall himself. It captures many essential qualities of the man, including his intellectual brilliance, his moral determination, his physical courage, and his earthy, sardonic humor. But in the end the book is too often anecdotal and rambling, failing to describe adequately the legal background of Marshall's actions and lacking the richness and complexity that Marshall and his career embody.

One of the best aspects of Rowan's book is his emphasis upon those qualities that Justice Marshall uniquely brought to the Court. He was its only member who ever practiced criminal law, let alone defended dozens of men accused of murder. He was its only member who ever faced racial discrimination, let alone experienced a real fear of being lynched when he tried cases in small southern towns. He was its only member who had successfully argued dozens of cases before the Court, let alone achieved landmark victories that expanded the meaning of the due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In describing Marshall's judicial performance, Rowan disposes decisively of the canard that the Justice's law clerks wrote his opinions for him. Certainly when I was his law clerk (1962-63), there never was any doubt of who was the judge. Once, when I argued a point too long, Marshall pointed to the framed document on the wall and said impa- tiently! "John F. Kennedy signed my commission. Who signed yours?"

For all of his eminence as a lawyer and judge, Marshall never lost his sense of humor. When President Nixon asked Bethesda Naval Hospital to send him a full report on Marshall's hospitalization for pneumonia in 1968, Marshall told the physician to put at the bottom of the file, "Not yet." His skill and charm as a story teller remain legendary.

Marshall's determination to defend his view of the Constitution grew with the years, even as he became more disillusioned with the direction the court was taking. He frequently told friends, "I was appointed for life, and I intend to serve out my term." Yet advancing age finally caused him to step down in June 1991. From that day until his death, he maintained a discreet silence about judicial matters.

But Rowan has no doubt, from his conversations with Marshall, of the justice's view of his successor, Clarence Thomas. Rowan writes, "Marshall would shake his head in wonderment that a black man who grew up poor in Jim Crow Georgia, and who had benefited from a thousand affirmative actions by nuns and others, and who had attended Yale Law School on a racial quota, could suddenly find affirmative action so destructive of the characters of black people."

The generation of AfricanAmerican lawyers following Mar- shall must surely contain lawyers of comparable capacity. Yet Rowan reports that of the 115 judges appointed to the federal courts by Presidents Reagan and Bush, only two were African-American (and one of those was Clarence Thomas). These statistics read as an indictment of the Presidents responsible for them.

When Justice Marshall announced his retirement, a reporter asked him how he wanted to be remembered. He replied, "He did the best he could with what he had." As the result of that effort, those who admire Thurgood Marshall may yet see his heroic ideals triumph. It is sad, however, that when that day comes, Justice Marshall will not be here to experience what Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. once called the "subtle rapture of a postponed power."

PRESIDENT FREEDMAN was apallbearer at Justice Marshall's funeralin the National Cathedral,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

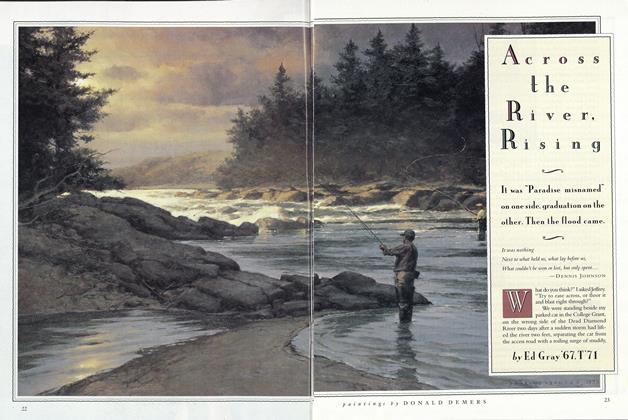

FeatureAcross the River, Rising

May 1993 By Ed Gray '67, T '71 -

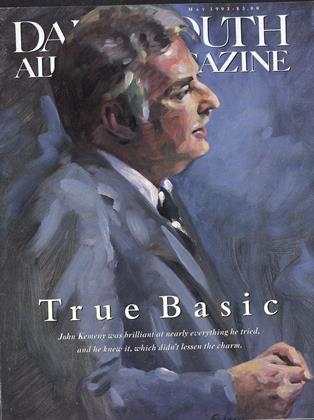

Cover Story

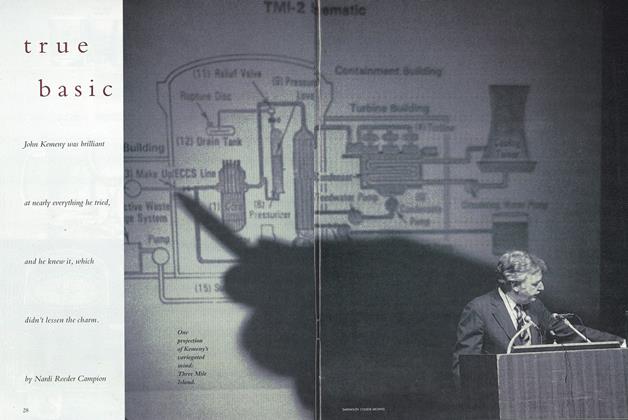

Cover StoryTrue Basic

May 1993 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

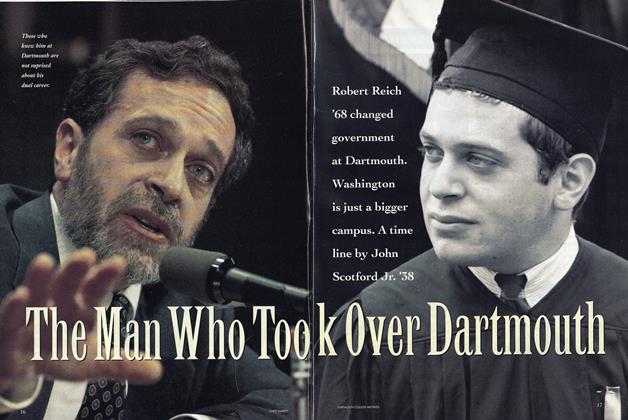

FeatureThe Man Who Took Over Dartmouth

May 1993 By John Scotford Jr. '38 -

Article

ArticleWomen in Love

May 1993 By Katharine Gingrass-Conley -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

May 1993 By E. Wheelock -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

May 1993 By Rick Joyce

James O. Freedman

-

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIs "The College" a College?

December 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Lifelong Pursuit of Education

Winter 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleLiving Well by Doing Good

NOVEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleLibraries Unbound

JANUARY 1998 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleBack to the Future

JUNE 1998 By James O. Freedman