Love is a very gendered thing.

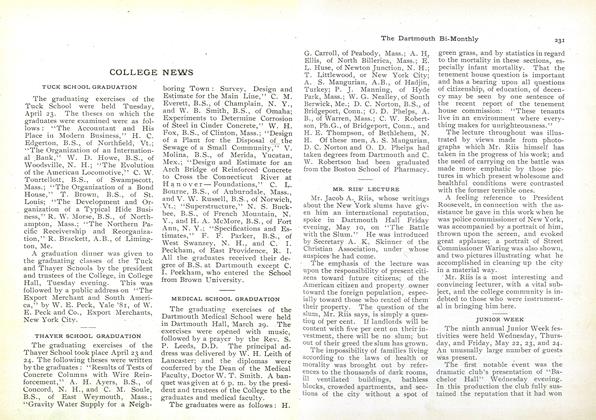

DO WOMEN DESCRIBE women in love differently from the way men do? Do the perspectives of male and female authors change from the twelfth to the twentieth century? How is gender noticeable in their writing? These were a few of the questions that helped shape the introductory French literature course I recently taught. Such a universal image as "women in love" seemed an ideal starting point for comparing texts spanning the French literary canon. Besides, everyone is interested in love, and I hoped that would stimulate class discussions. (It did.) I myself was curious to see how the grouping of the texts I chose for the course would affect the way I read them; I had read all of them more than once before, but never in the context of this particular theme.

We read three works by women, three works by men, and one work whose authorship is a matter of debate. We began with "Fresne," a story by France's first female author, known simply as Marie de France. In "Fresne" Marie de France tells the story of a young girl whose mother had given her up in infancy. She grows up in a convent and becomes famous for her beauty and grace. A nearby lord falls in love with her and she willingly accompanies him to his castle. Because his vassals do not know she is of noble birth, they pressure the lord into marrying a more suitable bride, that he might have an appropriate heir. But on the night the lord is to marry the other woman, the bride's mother recognizes the coverlet Fresne has delicately spread out on the bridal bed and realizes that Fresne is her abandoned daughter the twin of tire bride-to-be. Fresne is recognized by her parents, and she rightfully marries the lord she loves and all ends well.

Two elements are particularly striking in this story: the description of the seduction of Fresne by the lord is left out (whereas the recognition scene is recounted in some detail); and Fresne willingly offers her love, without any reticence. In this twelfthcentury text by a woman author, a young woman feels free to act upon her desire and in so doing retains her integrity within the text. Throughout she is described as virtuous. Love in this story, particularly Fresne's love for her lord, is unmediated by the pressures of political or economic alliances. It is an emotion freely expressed and given.

Next we read poems by two well-known Renaissance poets, Pierre de Ronsard and Louise Labe. In one respect, Ronsard did not belong in the course: he describes not women in love, but himself in love with women who, for the most part, do not return his love. Yet, reading Ronsard together with Louise Labe, who also wrote about unrequited love, enabled us to see how a male and a female writer handled the same theme. In Sonnet II Labe laments: "You've borne and struck my trembling heart by choice;/ Yet not one spark on yours has done the same." Her poems differ from Ronsard's in showing that women are not always cold, nor are men the only ones vulnerable to the pains of love. Furthermore, Labe shows in Sonnet XVIII that when her love is returned, she, like Fresne in Marie de France's tale, welcomes it: Kiss me. Again. More kisses I desire.Give me one your sweetness to express.Give me the most passionate you possess.Four I'll return, and hotter thanthe fire.

Then there is Phedre, the heroine of Jean Racine's famous seventeenthcentury play, who would willingly welcome love if she could, but she cannot because she is tragically in love with her stepson. Racine masterfully dramatizes her tormented desire and guilt, culminating in her suicide in the final scene. Phedre does her best to hide her love, revealing it only reluctandy, at times almost unknowingly. Her struggle is principally with herself, instead of with her lover. By her own account, and by the standards of behavior set forth within the play, her love renders her monstrous, the sad opposite of the ennobling effect love has on Fresne.

A different struggle may be discerned in the anonymous Letters of aPortuguese Nun. Over the course of five letters to the French soldier who seduced her and then left her behind in Portugal, Mariane uses all her persuasive powers in an effort to seduce him back through language. In the end she concludes that his rejection is hardest on her not because it forces her realistically to give him up, but because it forces her to give up the pleasurable passion he has awakened in her. For some time now, critics have argued that these letters are a hoax, that they were written by Viscount Guilleragues, the man who claimed to have "found" and published them. This argument is based partly on the assumption that the letters are too good, too literary, to be genuinely sincere, and that therefore they must have been written by a man. On the other hand, certain critics claim to have discovered the true identity of Mariane (Mariana Alcoforado) and her lover (Noel Bouton de Chamilly), while others simply question the notion that a woman could not have written the letters as well as a man.(Most of the women and all of the men in the class believed that a woman had written' them: again because of the way in which Mariane expressed her desire.)

We next read Guy de Maupassant's touching "Story of a Farmgirl," in which Rose, the protagonist, is willingly seduced by a farmhand who then leaves her. She gives birth to a child in secret and leaves it at a farm some distance from where she works. When the farmer she works for wants to marry her, she refuses because of her secret child. He insists. He beats her when they have difficulty conceiving their own child. She finally reveals her secret and he is pleased to adopt her child. Although written by a man, this story again portrays a woman who willingly gives her love and who is rewarded, not punished, for telling the truth.

The last work we read was Marguerite Duras's The Lover. This very effective novel is about a formative period in a woman's life, filtered through 50-year-old, non-chronologically ordered memories described vividly as they surface. Again in a work by a woman, we find a description of a woman who follows her desire without hesitation. The novel is as much about the protagonist's relationship to her family as it is about her feelings for her lover; just as in the Maupassant story, Rose loves her son as much as, if not more than, either of the other men in her life. Duras shows love to be a defining experience that contributes to shaping the protagonist's character.

By the end of the course we had been struck by how often authors expressed similar emotions, despite widely disparate social situations. Marie de France, Louise Labe, Marguerite Duras (and also Mariane) all express the desire to love openly and freely and insist upon seeing love as a virtue, no matter its circumstance; none of these loves was sanctioned by marriage, for example. Only in the works by men do the protagonists, Phedre and Rose, suffer from guilt. All of the women in love we read about broke some kind of social code: by loving out of wedlock (Fresne, Labe, Phedre, Mariane, Rose) or by breaking the law of the land (against incest: Phedre), or of the church (Mariane). The record of their experience dramatizes the way in which women's loves and desires have traditionally been viewed as a potential danger to malebased society. The loves of Fresne and Rose are reconciled with social order by marriage and adoption, and Phedre's love is resolved by her suicide. But the loves of Labe, Mariane, and Quras (and Ronsard, because he, like Mariane, was a member of a religious order) remain outside social convention.

Finding such striking similarities, particularly in the writing by women, exceeded my hopes that we would find a few common themes in the readings. Then, too, the ability of the women writers whether from the twelfth or the twentieth century—to surprise us with the complexity and frankness of the emotions they express, confirmed my belief that the women's writing would stand up to that of the men, including such recognizably great writers as Ronsard, Racine, and Maupassant, all of whom were much appreciated by the class. The class's preferred "women in love"? The protagonist of Duras's novel, Mariane (the Portuguese nun) and Louise Labe all examples that women, not just men, are great stylists, and have been so for far longer than we as a culture have at times been willing to acknowledge.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

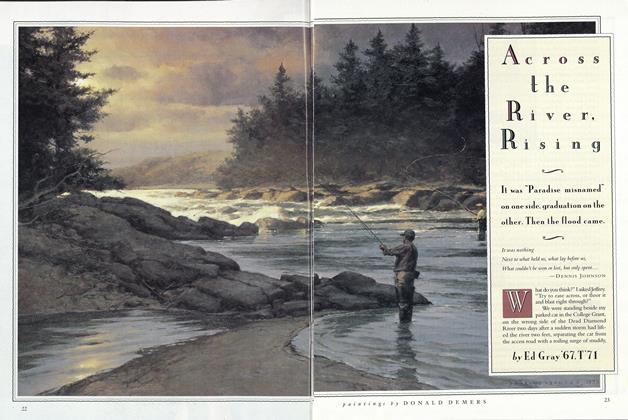

FeatureAcross the River, Rising

May 1993 By Ed Gray '67, T '71 -

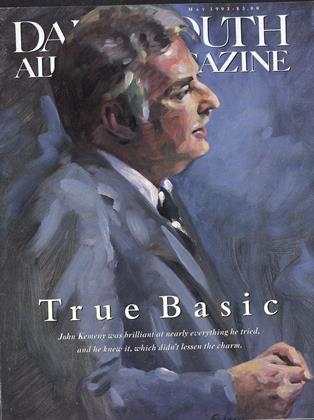

Cover Story

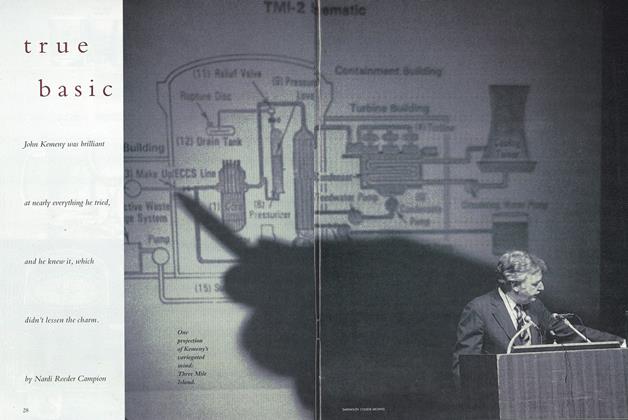

Cover StoryTrue Basic

May 1993 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Feature

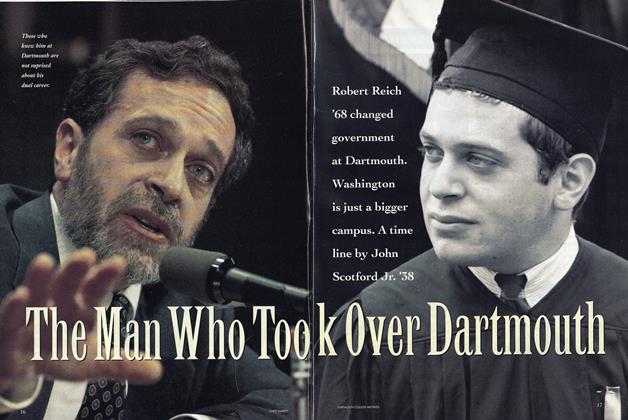

FeatureThe Man Who Took Over Dartmouth

May 1993 By John Scotford Jr. '38 -

Article

ArticleA Postponed Power

May 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

May 1993 By E. Wheelock -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

May 1993 By Rick Joyce