Notes From Alumni

It IS SIGNIFICANT THAT PRESIDENT Freedman, in his speeches and in this magazine's "Presidential Range" column, has chosen the playwright and Czech President Vaclav Havel as a great exemplar for the class of 1996. I share President Freedman's admiration of this man who helped launch the "Velvet Revolution" of 1989 But Havel could serve as more than a noble .example for American students. He could someday become a brilliant teacher.

I had the opportunity to witness the man's eloquence firsthand last September—at about the same time that Freedman was praising Havel to Dartmouth students. I was in Prague on assignment from IBM's employee magazine, Think, to interview the stocky, warm, and modest 58- year-old Havel in his sparsely furnished office. He was dressed in a short-sleeved blue shirt, blue sweater vest, and baggy brown pants. He wore glasses and puffed on a cigarette as he spoke in a friendly but intense tone.

As a playwright serving in government, he has set an example for others to follow. I asked him if he would like to see more intellectuals— authors, writers, artists Join him.

"This need to mobilize the human spirit and the human conscience, in its broader sense, is at the same time an appeal to intellectuals to participate more in politics. Intellectuals could, due to their dispositions and orientations of their thoughts, be destined to understand, to sense the broader responsibilities, and to be conscious of interrelationships and therefore more capable of holding office.

"Obviously," he added, "this cannot be applied mechanically in the sense that every poet would be a better member of Parliament' than a lawyer or technician It is nonsense. We differ from each other, some being suitable for politics and others not. In any case, it seems to me that it is time for an appeal to intellectuals to participate more in politics."

This last statement suggests a converse one: while an intellectual has much to bring to politics, an intellectual with political experience has much to teach other intellectuals. When President Havel chooses to return to private life, Dartmouth should extend an invitation to him. A severalmonth sabbatical would do both him and the College good. I may sound a bit too anticipatory here, but it is not too early to establish a relationship that could lead to a short-term teaching position. Dartmouth is unique in having a program established by the Montgomery family to bring worldclass individuals to campus. As a Montgomery Fellow, Havel would join the ranks of people both of depth and breadth who have served in the past: Carlos Fuentes (another literary politician), Madeleine Kunin, Toni Morrison.

Dartmouth will have to wait, perhaps a long time, before it can hope for Havel's presence on campus. In the meantime, the president and Dartmouth will undoubtedly continue to nurture relationships with people who can teach as well as do. What other Vaclav Havels are there out there who balance what Freedman calls their private and public selves?

The Montgomery tradition follows on the example of Dickey's Great Issues course. Higher education in turn, often rightly criticized for its insularity and irrelevance to society, could learn from Dartmouth's example.

What is the value to education of anintellectual who has run a nation?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureRobert Christgau's Ear Turns '51

April 1993 By BILL GIFFORD '88 -

Feature

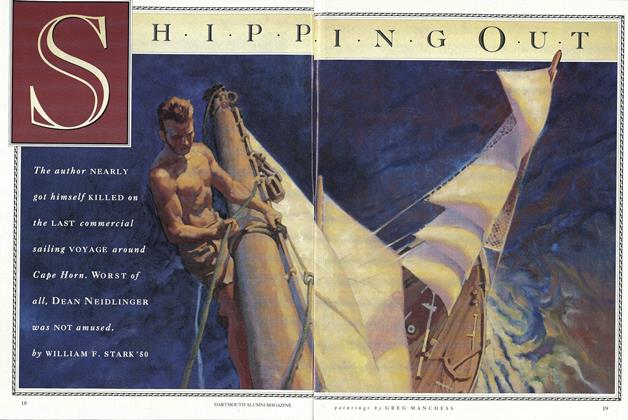

FeatureShipping Out

April 1993 By WILLIAM F. STARK '50 -

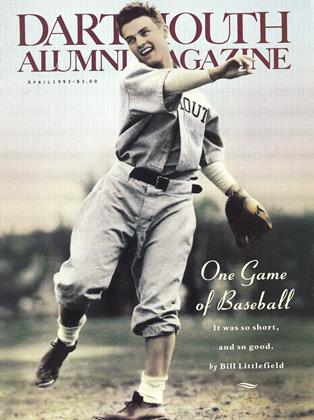

Cover Story

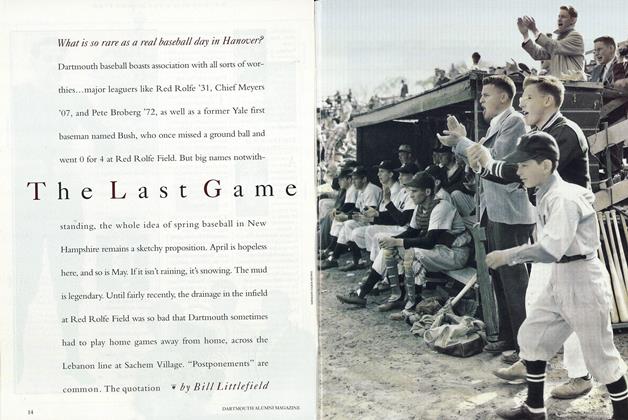

Cover StoryThe Last Game

April 1993 By Bill Littlefield -

Feature

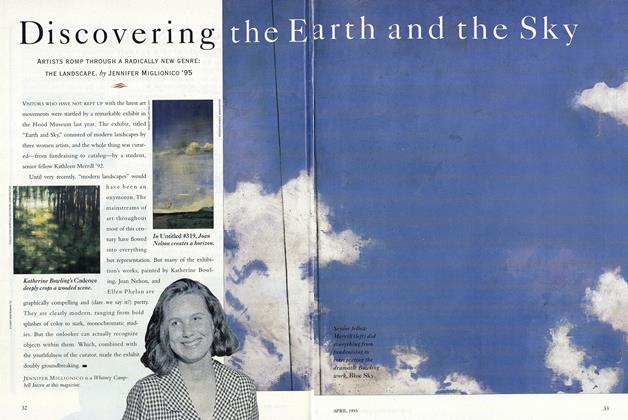

FeatureDiscovering the Earth and the Sky

April 1993 By Jennifer Miglionico '95 -

Article

ArticleSchools for the Twenty-First Century

April 1993 By Professor Faith Dunne -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

April 1993 By "E. Wheelock"

Woody Klein '51

Article

-

Article

ArticleGLEE CLUB WINS HONORABLE MENTION

April 1921 -

Article

ArticleCLASS SECRETARIES MET IN HANOVER APRIL 22, 23

May 1921 -

Article

ArticleTwo New Studies

February 1951 -

Article

ArticleRecord Fund Pace

June 1974 -

Article

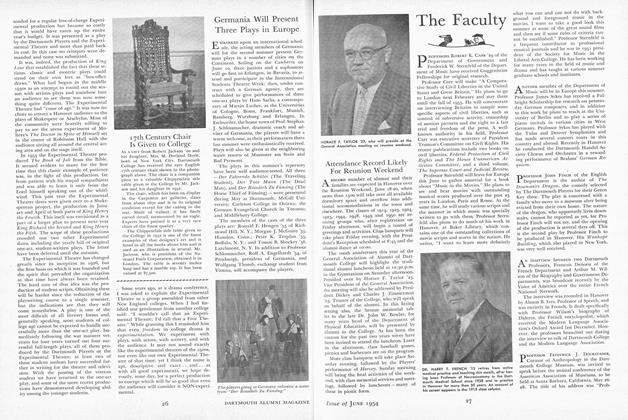

ArticleThe Faculty

June 1954 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Article

ArticleNeed a Change of Pace?

April 1952 By PROF. HERBERT W. HILL