Ah, a good novel. Whether you are riding a train, relaxing on a beach, or unwinding before sleep, a novel means time out from your own life. You are willed into another's being, another's story, across centuries or cultures. Yet, unlike other forms of storytelling theater, films, poetry, myths the novel offers a uniquely intimate experience. It is not performed, it is not recited aloud. It is a realm you enter alone. "When you read a novel," says English and comparative literature Professor Peter Bien, "you have a book in front of your face that blocks out everything else in the universe."

For the record, when asked to tell us why the novel matters a topic he discussed with alumni groups years ago Bien prefaced his remarks with the conviction that "all literature matters. Why? Because literature is a culture conversing with itself and examining its innermost being."

Bien has been both a listener and a speaker in that conversation for years and he has been doing it not only in English but in Greek, which he picked up when he married a native of Thessaloniki, Macedonia. He, his wife Chrysanthi, and Dartmouth colleague John Rassias co-authored a pioneering textbook on colloquial Greek, Demotic Greek, used worldwide. (It was also Rassias's first venture in language textbooks.) Bien is an expert on the Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis, whose The Last Temptation of Christ is among the many works that the professor has translated into English. So extensive are Bien's contributions to the field of Greek literature that they themselves will be the focus of an international conference to be held in England next year.

He has played an equally influential literary role at Dartmouth, where he has taught since 1961. As the Ted and Helen Geisel Third Century Professor in the Humanities, he founded the College's Composition Center in 1974 to help students hone their literary skills. He also established the College's University Seminars program to unite scholars in cross-disciplinary inquiry. Currently the Frederick Sessions Beebe '35 Professor in the Art of Writing, he is preparing to teach in this summer's Alumni College on Great Literature Reinterpreted, a look at why there are changes in how literature is taught. "One way we can measure cultural change is through the history of criticism how we look at literary works," he says. "A work is different in every generation."

The novel is very much part of that ever-shifting literary flow. The novel "mirrors our culture, one in which individualism, historicism, and particulars are king," says Bien. It was the Age of Reason, he explains, that swept the novel into existence in eighteenthcentury England. Novels constituted the literary equivalent of that age's scientific and logical investigation into the details of the world. For centuries poetry and drama had served a vastly different worldview, the Ptolemaic and Christian vision of the universe as a closed system created by God in its entirety. Heirs to an age-old oral tradition, poems and theatrical productions recycled ancient myths and

legends. "The literature of those times couldn't have the historical viewpoint that we have now," Bien says. "Every plot was an equivalent of something else. It wasn't individualistic." By the time of the Renaissance, philosophers were looking beyond universals to the notion that reality resides in particulars. Yet it was only slowly that the individual took on the importance once reserved for the type, says Bien. Shakespeare's dramas are a transitional case in point. "Henry IV is not solely about Henry," says Bien. "It's about kingship." With the rise of novels, characters and plots no longer sprang from mythology", legends, and universal types. "They had become particularized in terms of time and place," says Bien. "They had become historical."

Literature's late bloomer, the novel is now the dominant way our culture talks to itself story by story, reader by reader. Ironically, however, given the centuries it took for individual visions of the world to rise to the top of the cultural mountain, the novel has found itself limited by its own particulars, according to Bien. "In the twentieth century, the novel aspired to become poetic and to speak about universals, the great example in our time being James Joyce's Ulysses. It is true that if Dublin burned down you could rebuild it by using Ulysses as a guide the book is so particularized; yet what is really projected in that novel is 'city-ness' as a universal." By the late nineteenth century, as evolution, anthropology, geology,, and related fields were displacing God, Bien explains, "people yearned for new universals to replace what had been lost. Joyce tried to find universals both in culture and nature in order to provide a sense of ultimate value." Such Herculean literary ventures can be especially daunting to the lone reader. "Modern novels are difficult," Bien says. "Thus they are best read in a communal setting, not just in front of your face."

The professor sees another reason for reading novels communally: making the most of the novel's unique potential for bringing the world's peoples together. "Novels, more successfully and easily than poetry, can be translated. The novel brings tremendous cross-fertilization across cultures," he explains. Long attuned to the strengths of shared thoughts and lives (he helped develop the Quaker idea of Kendal retirement communities based near American college campuses), Bien would like to see novels increasingly used to build community. "We need to make the very process of reading novels less individualistic and more shared and the best place to do that is in the classroom," he says. Ultimately his approach to literature is about something greater. "Human life," he says, "is realized most fully only in community."

Literature'slate bloomer,the novel isthe dominantway ourculture talksto itself.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

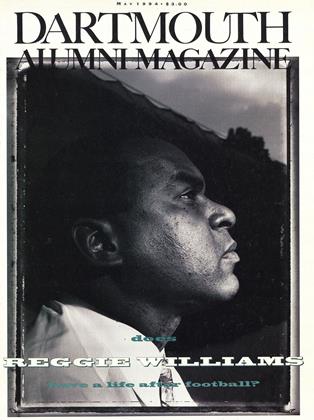

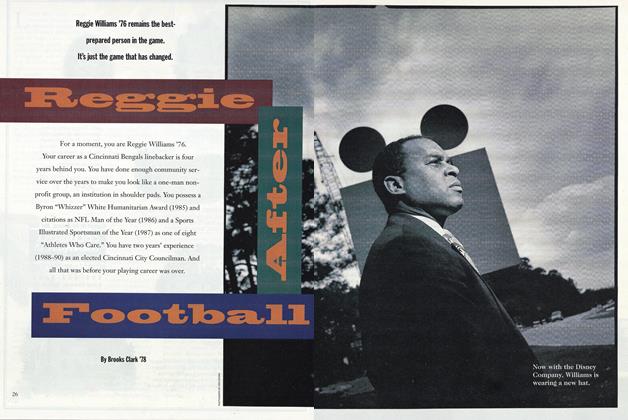

Cover StoryReggie After Football

May 1994 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

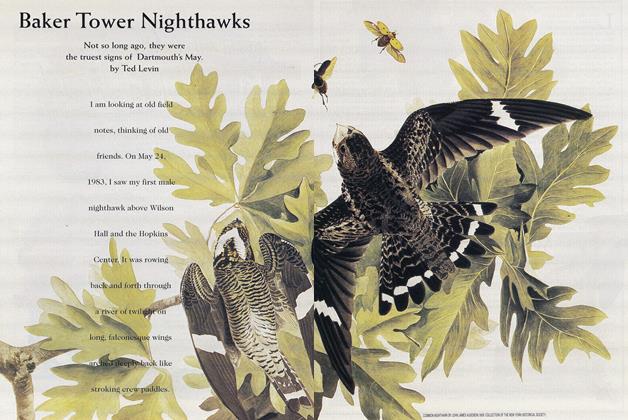

FeatureBaker Tower Nighthawks

May 1994 By Ted Levin -

Feature

FeatureCOOL STUDIES

May 1994 By KAI SINGER 95 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

May 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

May 1994 By W. Blake Winchell -

Article

ArticleWorries of a President

May 1994 By James O. Freedman

Karen Endicott

-

Feature

FeatureIs Vietnam Still Claiming Some of Us?

December 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Hero in American Education

NOVEMBER 1989 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleProfessor Sergei Kan:

September 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleOut But Not Down

May 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe Daughters of Eve

October 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWHAT HAPPENED TO THE DEMOCRATS?

APRIL 1989 By Robert Arseneau, Karen Endicott