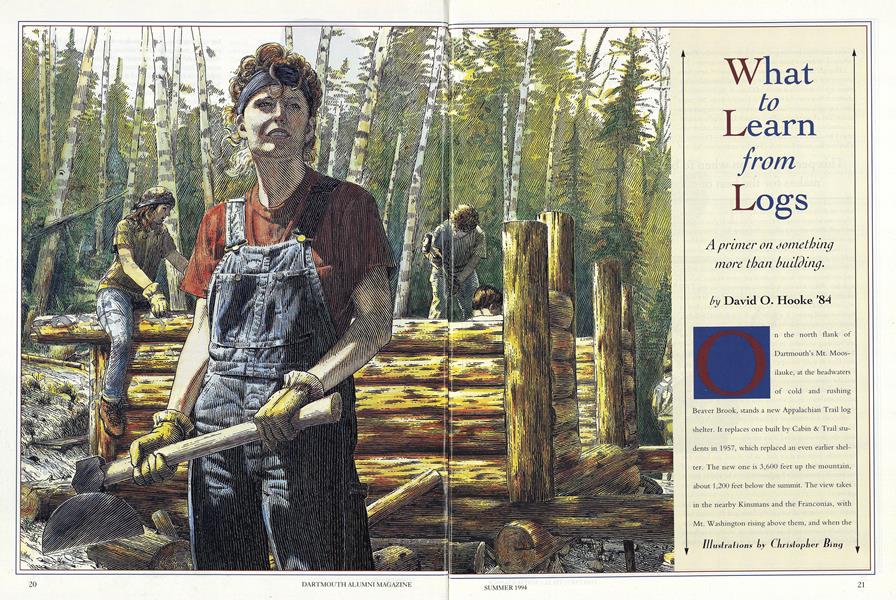

A primer on something more than building.

On the north flank of Dartmouth's Mt. Moosilauke, at the headwaters of cold and rushing Beaver Brook, stands a new Appalachian Trail log shelter. It replaces one built by Cabin & Trail students in 1957, which replaced an even earlier shelter. The new one is 3,600 feet up the mountain, about 1,200 feet below the summit. The view takes in the nearby Kinsmans and the Franconias, with Mt. Washington rising above them, and when the leaves are off the birches you can see the rest of the Whites, nearly all of them, a great crinkled mass of blue-green.

Though there was a substantial amount of help from alumni and numerous donations from longtime trail volunteers, it was up to the students of Cabin & Trail to build the shelter. It was a crucial time for the organization. No major new log-cabin project had been undertaken in the past three years. The chain of specialized knowledge, largely student-acquired for 80-odd years, had been stretched to near breaking. The students fell back on the old guard—Director of Outdoor Programs Earl Jette 'ssa, Kevin Peterson '82, and me—to design the shelter and supervise its construction. There was a larger purpose to our involvement than the shelter itself: We were rekindling a flickering fire, attempting to spark the interest of a new generation of log-cabin builders.

This was not hard; few experiences could be more powerful for a student than to stand, blistered and sap-stained, on that windswept mountainside, measuring the progress in logs laid on. But interest alone does not prepare a student to build a shelter. What does that is the sort of preparation that is not taught in the liberal arts, and is taught less and less in the rest of society. It is nonetheless an important education. And so here is a small primer. It will not teach you to build a shelter, but it may prepare you for the education.

To build a shelter, you must first understand what you are building, and why. In hiking parlance a shelter is a rectangular building with walls on three sides, low in the back and high toward the open front, generally with a plank floor and a roof that overhangs the front opening to keep out the worst of the rain. Most DOC shelters are made of logs, and these logs were cut off the land locally, and the whole shelter is built simply and roughly. Roofs are of metal or asphalt shingle.

Shelters are therefore a peculiar piece of architecture. Though generally watertight and oriented so as to face away from the prevailing wind, they are completely open to the elements. The outside is always present. In a cabin, with its four walls, there is a door that can be closed, gas lights that can be turned on, a stove that can be cranked up to stave off the outside. Even a tent has doors that can be zipped closed. But in a shelter the outside is ubiquitous, impossible to ignore.

The shelter therefore compels an inclusive ethic. Lie inside with your head toward the front, and the woods surround you. The truce with nature is blurred and uncertain. In a shelter everyone sleeps on the floor, on the same level, and etiquette forbids one from sleeping parallel to the back wall, hogging the warmth and roof. Everyone has just about an equal shot at being soaked by rain or caressed by wind. In this uncertainty lies the paradox that shelters are among the most comfortable places on earth—a rudimentary bend to the needs of the human anatomy, no more, pulling forth in a completely different context Melville's wisdom that without some small discomfort one cannot truly be comfortable. The luxury of a feather bed is best felt in a cold room, he said. He doubtless would have appreciated a shelter: Stretched out flat on a thin foam pad in his bedroll on the plank floor, warm and dry against an October night's lick of frost, the pack's weight off his shoulders, the great author would have watched the eternal stars wheel by and listened to the brook chuckle, and he would have felt confirmed, complete.

To create such a structure, you must see how others have been built. A scholar on campus would call this a literature search. Try to find the builders. Learn their biggest lessons, listen to their most important mistakes, have them tell you what humbled them. Picture every step of that process, and then form a picture of your own. When you build a shelter, the crystallizing moment comes when you have the whole thing in your mind, like a kind of story—not the last detail, but the shape of things to come. The characters of this story are the logs: You must know what you have to work with and how you will use it. A log shelter is not a structure made of logs, but a collection of individual logs made into a shelter. You will be thinking constantly of the order the logs will go in, balancing the taper and the bends, saving the long straight ones for the roof, using the imperfections of the others not so much to cancel each other out as to complement each other. You must, in short, think about how to think, which is at the heart of being a practical idealist. The logs do not allow straight-line planning—an exact determination of what to do in advance. Logs are not straight, and neither must be your plan. It must bend and twist as the logs do, or as the plot of a good story is shaped by the characters.

This is not a license to be slapdash. Certain parts of the job require great precision and time. The cornerposts, which define the whole shape, must be hewn properly to create the two perpendicular planes that embody the corner, and then they must be dead vertical and well braced, or some overzealous log-installer will knock the whole building out of true. There is no magic formula that tells you when precision matters and when it doesn't, but with practice, you will learn it. My rule of thumb is this: Lines that one expects to be parallel—such as the top of the front opening and the floor below—are worth dithering over. The people who will help you best are the ones who have experience making those judgments. In fact, this perspective on when to be precise, and when not to be, makes for the best of companions in any enterprise.

Chances are, you will come to the shelter site without knowing your fellow builders very well. The virtual building in your head must be reconciled with the virtual buildings in their heads. But you will adjust: the building with the site, your building with the ones your companions want to build, your desire to use simple tools with your need to work quickly.

The first adjustment will come with the reconciliation of your ideal drawing to the reality of the site. Rare indeed is the trail shelter built in a flat open field. The more spectacular the setting, the more challenging the work. When cleari ng the trees from the site, you are creating an opening, and if you are on a mountainside, a view. You are also creating a human intrusion into the woods, and the price of that intrusion is mud. As you cut into the hillside to make foundation pads and level the site you create a hill of slippery ooze; unless you are on very well-drained soil, the mud will be treacherous. Every enthusiastic hoisting and dragging of a log must be tempered with clear-headed thought on the physics involved, the consequences of slipping at a critical moment. Time must be taken to build ramps, rough scaffolding, and other aids that will allow large actions to proceed incrementally. And when all is done, time must be given to repair the damage, to cleat the hillside "with logs and rocks to prevent erosion and heal the scar as much as can be.

Then when it comes to actual building, there is an order, and you should know it, and you must follow it. This is probably true of life, except that in shelters the order should be obvious and mistakes are more apparent. First the logs must be cut and peeled; bark keeps the wood's moisture in and causes rot. This work is undemanding and necessary, an excellent icebreaker. A dozen conversations will be spinning at once around this mindless labor.

The foundations and first front and back sill logs determine the size, level, and square of the building. Rock foundations must be built for the foundation logs. Large rocks, the larger the better. Getting four sets of large rocks (ideally six, one in the middle of the front and back) into a rectangular and level arrangement is the first and among the most critical tests of your standards and patience. There is also some math involved. Euclid's 3-4-5 triangle is a reliable way of creating .perpendicular lines. Don't be ashamed to use what you know.

Even at this first stage, you must think about gravity. The temptation to lift a heavy log can be overwhelming for a young man in the woods, especially a man who has never learned the lifelong need to compromise. Dragging is more tedious and less dramatic, but the builder's back is less likely to be crippled. Four people with a rope can easily drag a large log if a fifth person uses a five-foot iron bar to keep the log's end from burying itself in the dirt (gravity again). Learn the timber hitch, an excellent knot for dragging because it is easy to untie. Get used to the heft and feel of that bar. It is the crudest, and among the most useful, of all the tools you will ever use. Your choice of tools will say a lot. It is not shameful to use a Chainsaw but it is good not to use power tools at all. It is a measure of how far removed from hand tools we have become that it surprises people to hear you can build a log shelter construction without a chainsaw and sometimes faster. Students in the 1930s built Dartmouth's Moosilauke Ravine Lodge, the largest log building in New Hampshire, under the direction of Ross McKenney, Dartmouth's pre-eminent woodsman, almost entirely by human and animal power, in the space of six months; the only exception was a gas-powered cement mixer. McKenney also created an intercollegiate contest in the use of traditional woods skills and tools, and I am fortunate to coach that team. Skills learned there allow students to build without artificial power if they choose. I hope they do. They will feel the bite of a broadax into green spruce, and hear the clanging of steel on a hard knot, and smell the mix of sweat on old polypropylene with the sweetness of balsam and the subtle breath of mud, rather than the brassy reek of gas and exhaust, and they will know the pride of old tools wellkept. If they swing their ax properly, they will earn a particular kind of blister that is the pride of a new woodsman. For right-handed choppers, the sore is on the first knuckle of the left thumb and is caused by the right hand, which glances off it as the two hands come together on the ax handle. This only happens if the chopper slides the right hand up the handle to raise the ax, and then back down onto the left during the swing—offering vastly more power and control than the standard two-handed baseball swing.

Perhaps the greatest boon of working with hand tools alone is improved communication. The chainsaw seems designed for isolation—right down to the cumbersome headgear and chaps that have to be pulled on like armor before one can do anything at all. Hand tools, by comparison, still require care, but one can still talk and listen while using them, and in fact this is a base imperative when two people work a cross-cut saw. There is a tension that comes from placing a human building into the non-human woods, and at times, especially in the early going, the noise of a Chainsaw so audacious and out of place, heightens the tension, the sense that, in the silence that follows, the woods are crying. Yet humans are every bit a part of nature; the subtle rasp and chop of saw and ax allow the communication about place, right, and belonging to be a dialogue rather than a diatribe. It is better for building friendships, too.

Once the foundations and front and back sill logs are in place, the next step is notching the bottom logs of the side walls so that they fit onto the sills to make a rectangular base for the building. No, actually, that is not the next step. The next step is to plan the notching. Building from logs makes a person circumspect, untrusting of absolutes. The carpenter's rule to measure twice, cut once, seems to a log builder a flighty and ill-considered plan. In building a shelter, especially in laying out the foundation, you must measure many times and plan for your measurements to seem to change before your very eyes. The notches must be such that the front, back, and side logs fit together tightly. Since both notches on the side logs must be made at once—allowing the log to settle perfectly onto the two sills—the time to get both notches right is in the marking up, in advance of hewing the notches. After you hew out the notch you inevitably will have to adjust your work to get the fit right, but overzealous or ill-planned notching could result in a log wasted.

Then it is time to erect the four corner posts, first hewing them square on two sides (a solid geometry topic in itself) and then standing them at the building corners and bracing them square. With the building now defined, the wall logs can begin to go into place. Notice that once peeled and lying together the logs are no longer the straight, uniform nonentities you thought they were. Suddenly they have numerous knots and bulges. Cut each log to length, and set it roughly in place. Rotate the log until its imperfections marry the one below. The peavey, a pike with a hinged hook that revolutionized the logging industry in the 1860s, allows you to grip and turn a log easily. Mark an arrow on the end of the log to show which side is up. A lumber crayon is the tool for this; be in the habit of carrying one. Once the best fit is found, aim to make the fit better. Note where the logs touch, and how wide the gaps between. In an ideal world, the logs would touch along their entire length. If the ideal is important to you, and you are willing to spend the time, you can hew each log along its entire length. Or you can rig a portable saw jig and mill the logs to make them uniform. It is your choice: to work with or against the logs. I, for one, like to use the irregularities in a log, to take advantage of them. In this sense, too, logs have something to teach us about ourselves and what we do and what we aspire. I will not say what this lesson is, because it is better learned on site than on paper, and I'm not sure how to explain it (having been only recently married myself), except to note that imperfections are not always a bad thing.

It takes a good partnership to fit a log to its neighbor below. You must set it in place, teetering on the top of the partially built wall, and rotate the log 15 to 30 degrees at a time to find the best fit. You must argue the merits of a given presentation. You will reach a decision and prepare to mark the log's knots and bulges to be hewn to fit, just as you remember you have loaned your last lumber crayon to someone on the other end of the building. You must find another crayon, mark the log as accurately as you can, roll it back off, and set it on the crude staging you built the day before. Now you use a broadax, scoring with deep cuts that follow your marks and then hewing with cuts that lift off chips. You marvel at the broadax's simple efficiency. And you set it aside and muscle the log up to its place, setting it as it was supposed to fit. You and your partner realize that you skipped a high spot, and you argue whether it will do as is. You make the old joke for the hundredth time about not being able to swing a dead cat through the gap, compare the gap with other gaps, take the log back down, hew it some more, and replace it. Perfect. Take a spike out of its bucket, clean off the ice and mud, and drive it home. Stand up a bit stiff but a log higher, and go in search of the next log.

The tighter you get the logs now, the less effort you will have to spend chinking. Although making airtight a building that has one open side may seem foolish at best, the effort is always made—it is not just craftsmanship, it is the sense of security in knowing that there is a protected corner in which to huddle in the worst of gales. Moreover, the techniques are exactly the same for building a cabin, which could be your next project; there the gaps between logs become painfully obvious on a cold winter night.

It will not be long before you are building scaffolding to lay on the roof, and not long after that when you are getting the floor joisted and laid, creating a simple pattern of wide pine board by wide pine board, snug and tight. Six weeks altogether, and then it is no longer a project—an amalgam of logs and nails and lists and tools and food—but a place to sleep, a place where someone's family can be snug and safe and inside and still outside at the same time. Inside the shelter you, a student, provided.

You yourself will come back, at first often, then less so, then not at all for years after graduation. But the shelter will stay there, and it will mean something to you, like nothing else, except maybe a cabin. What you put into it is what it is, and what will last. As the singer Gordon Bok put it:

"...and here's to the carpenter, may patience guide your hand for the dearer the work is to you, the longer it will stand."

But your shelter will not stand forever, no matter how dear. It will be destroyed, through storm or carelessness or old age, and you will feel the loss deeply. This too is a lesson of building; it would be well to prepare for it, but I am not sure how it is done. The first Stoddard cabin stood only six years before it burned to the ground. Bob Smith '81, one of the cabin's eight builders, called a fellow member of the construction crew, Bill Hunt '80, to tell him the news. The two had not spoken in five years, but Smith had only to identify himself for Hunt to know the message. "What is the saddest thing you can imagine?" said Bob. But Bill was already imagining it: the chars where their labor of love had been. But it was not a total loss. The attachment you get to a structure is directly proportional to the amount you have changed yourself in the process of building it. It is more than memory, of the sawdust that leaked out of your socks when you pulled them off, or the impossibly deep fatigue at the end of the day, or the amazing taste of macaroni and cheese (a taste resulting more from context than ingredients), or the joy of the crew's geekiest member showing off the rock skidway he engineered to slither a half-ton boulder out of the site, or the lurid screech of a dull file on a dull ax, or the hands covered with pitch and mud like gloves, or the sudden realization of power by 15 people hauling a thousand-pound log with rope. It is more than memory, what remains of a shelter. It is a kind of talisman.

Thirty years from now, a gray-haired alumna from the class of '95 will walk up to the place she helped build as a student. She will set down her pack, and seek out a log in the back wall with an odd swirl of grain, a gall from where another tree leaned and rubbed against this one in its longago youth. She will rub her hand over the age-smoothed spruce and think back to the autumn day when she learned how to shape this misshapen log to fit its neighbor below. She thinks of a thousand storms and nights ridden out in cities wrapped in concrete, and of the countless strangers she has sheltered here in this space by that simple act of caring, of setting log on log and making this shelter real.

This is not a liberal art, this act. But it is no less an education.

This perspective on when to be precise, and when not to be, makes for the best of companions in any enterprise.

The attachment you get to a structure is directly proportional to the amount you have changed yourself in building it.

Semi-professional mountain man, DAVID O. HOOKE overseesseveral outdoor programs, including the Moosilauke Ravine Lodge.He is the author of Reaching That Peak: 75 Years of the Dartmouth Outing Club.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Onlyness of a Long-Distance Runner

June 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

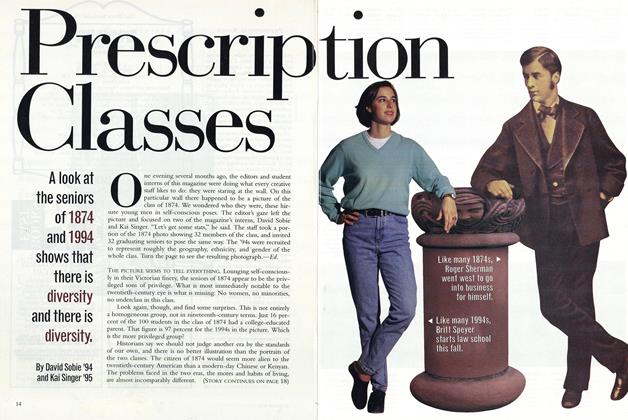

ArticlePrescription Classes

June 1994 By David Sobie '94 and Kai Singer '95 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

June 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleFilling The Power Vacuum

June 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1973

June 1994 By Donna Ferretti Tihalas -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

June 1994 By Brooks Clark

David O. Hooke '84

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA New Dimension in Dartmouth Education

MAY 1957 -

Feature

FeatureTV News Editor

DECEMBER 1969 -

Feature

FeatureHANDYMAN'S SPECIAL

APRIL 1989 -

Feature

FeatureTwelve Hours and Their Aftermath: The Student Seizure of Parkhurst Hall

JUNE 1969 By C.E.W. -

Feature

FeatureRecent Accessions in European and Graphic Art at The Hood

APRIL 1986 By Hilliard T. Goldfarb -

FEATURE

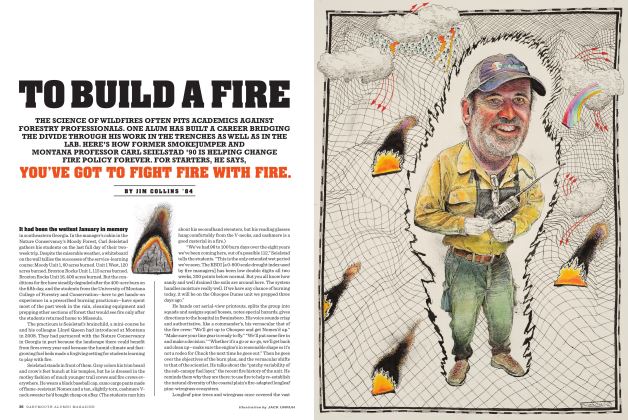

FEATURETo Build a Fire

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By JIM COLLINS '84