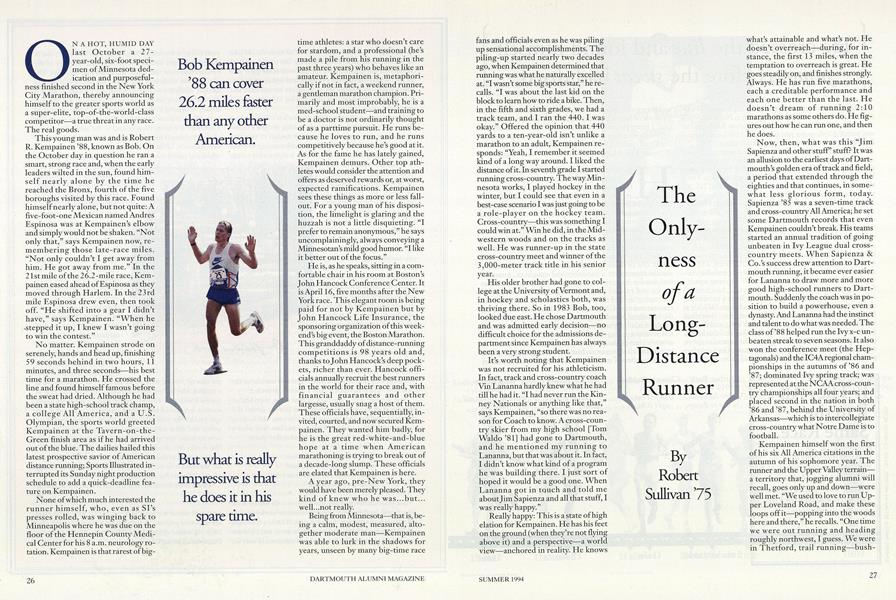

ON A HOT, HUMID DAY last October a 27-year-old, six-foot specimen of Minnesota dedication and purposeful-ness finished second in the New York City Marathon, thereby announcing himself to the greater sports world as a super-elite, top-of-the-world-class competitor—a true threat in any race. The real goods.

This young man was and is Robert R. Kempainen '88, known as Bob. On the October day in question he ran a smart, strong race and, when the early leaders wilted in the sun, found himself nearly alone by the time he reached the Bronx, fourth of the five boroughs visited by this race. Found himself nearly alone, but not quite: A five-foot-one Mexican named Andres Espinosa was at Kempainen's elbow and simply would not be shaken. "Not only that," says Kempainen now, remembering those late-race miles. "Not only couldn't I get away from him. He got away from me." In the 21st mile of the 26.2-mile race, Kempainen eased ahead of Espinosa as they moved through Harlem. In the 23 rd mile Espinoss drew even, then took off. "He shifted into a gear I didn't have," says Kempainen. "When he -stepped it up, I knew I wasn't going to win the contest."

No matter. Kempainen strode on serenely, hands and head up, finishing 59 seconds behind in two hours, 11 minutes, and three seconds—his best time for a marathon. He crossed the line and found himself famous before the sweat had dried. Although he had been a state high-school track champ, a college All America, and a U.S. Olympian, the sports world greeted Kempainen at the Tavern-on-the Green finish area as if he had arrived out of the blue. The dailies hailed this latest prospective savior of American distance running; Sports Illustrated interrupted its Sunday night production schedule to add a quick-deadline feature on Kempainen.

None of which much interested the runner himself, who, even as Si's presses rolled, was winging back to Minneapolis where he was due on the floor of the Hennepin County Medical Center for his 8 a.m. neurology rotation. Kempainen is that rarest of bigtime athletes: a star who doesn't care for stardom, and a professional (he's made a pile from his running in the past three years) who behaves like an amateur. Kempainen is, metaphorically if not in fact, a weekend runner, a gentleman marathon champion. Primarily and most improbably, he is a med-school student—and training to be a doctor is not ordinarily thought of as a parttime pursuit. He runs because he loves to run, and he runs competitively because he's good at it. As for the fame he has lately gained, Kempainen demurs. Other top athletes would consider the attention and offers as deserved rewards or, at worst, expected ramifications. Kempainen sees these things as more or less fallout. For a young man of his disposition, the limelight is glaring and the huzzah is not a little disquieting. "I prefer to remain anonymous," he says uncomplainingly, always conveying a Minnesotan's mild good humor. "I like it better out of the focus."

He is, as he speaks, si tting in a comfortable chair in his room at Boston's John Hancock Conference Center. It is April 16, five months after the New York race. This elegant room is being paid for not by Kempainen but by John Hancock Life Insurance, the sponsoring organization of this weekend's big event, the Boston Marathon. This granddaddy of distance-running competitions is 98 years old and, thanks to John Hancock's deep pockets, richer than ever. Hancock officials annually recruit the best runners in the world for their race and, with financial guarantees and other largesse, usually snag a host of them. These officials have, sequentially, invited, courted, and now secured Kempainen. They wanted him badly, for he is the great red-white-and-blue hope at a time when American marathoning is trying to break out of a decade-long slump. These officials are elated that Kempainen is here.

A year ago, pre-New York, they would have been merely pleased. They kind of knew who he was...but... well...not really.

Being from Minnesota—that is, being a calm, modest, measured, altogether moderate man—Kempainen was able to lurk in the shadows for years, unseen by many big-time race fans and officials even as he was piling up sensational accomplishments. The piling-up started nearly two decades ago, when Kempainen determined that running was what he naturally excelled at. "I wasn't some big sports star," he recalls. "I was about the last kid on the block to learn how to ride a bike. Then, in the fifth and sixth grades, we had a track team, and I ran the 440. I was okay." Offered the opinion that 440 yards to a ten-year-old isn't unlike a marathon to an adult, Kempainen responds: "Yeah, I remember it seemed kind of a long way around. I liked the distance of it. In seventh grade I started running cross-country. The way Minnesota works, I played hockey in the winter, but I could see that even in a best-case scenario I was just going to be a role-player on the hockey team. Cross-country—this was something I could win at." Win he did, in the Midwestern woods and on the tracks as well. He was runner-up in the state cross-country meet and winner of the 3,000-meter track title in his senior year.

His older brother had gone to college at the University of Vermont and, in hockey and scholastics both, was thriving there. So in 1983 Bob, too, looked due east. He chose Dartmouth and was admitted early decision—no difficult choice for the admissions department since Kempainen has always been a very strong student.

It's worth noting that Kempainen was not recruited for his athleticism. In fact, track and cross-country coach Vin Lananna hardly knew what he had till he had it. "I had never run the Kinney Nationals or anything like that," says Kempainen, "so there was no reason for Coach to know. A cross-country skier from my high school [Tom Waldo '81] had gone to Dartmouth, and he mentioned my running to Lananna but that was about it. In fact, I didn't know what kind of a program he was building there. I just sort of hoped it would be a good one. When Lananna got in touch and told me about Jim Sapienza and all that stuff, I was really happy."

Really happy: This is a state of high elation for Kempainen. He has his feet on the ground (when they're not flying above it) and a perspective—a world view—anchored in reality. He knows what's attainable and what's not. He doesn't overreach—during, for instance, the first 13 miles, when the temptation to overreach is great. He goes steadily on, and finishes strongly. Always. He has run five marathons, each a creditable performance and each one better than the last. He doesn't dream of running 2:10 marathons as some others do. He figures out how he can run one, and then he does.

Now, then, what was this "Jim Sapienza and other stuff' stuff? It was an allusion to the earliest days of Dartmouth's golden era of track and field, a period that extended through the eighties and that continues, in somew-hat less glorious form, today. Sapienza '5 was a seven-time track and cross-country All America; he set some Dartmouth records that even Kempainen couldn't break. His teams started an annual tradition of going unbeaten in Ivy League dual cross-country meets. When Sapienza & Co.'s success drew attention to Dartmouth running, it became ever easier for Lananna to draw more and more good high-school runners to Dartmouth. Suddenly the coach was in position to build a powerhouse, even a dynasty. And Lananna had the instinct and talent to do what Was needed .The class of '88 helped run the Ivy x-c unbeaten streak to seven seasons. It also won the conference meet (the Heptagonals) and the IC4A regional championships in the autumns of '86 and '87; dominated Ivy spring track; was represented at the NCAA cross-country championships all four years; and placed second in the nation in both '86 and '87, behind the University of Arkansas—which is to intercollegiate cross-country what Notre Dame is to football.

Kempainen himself won the first of his six All America citations in the autumn of his sophomore year. The runner and the Upper Valley terraina territory that, jogging alumni will recall, goes only up and down—were well met. "We used to love to run Upper Loveland Road, and make these loops off it—popping into the woods here and there," he recalls. "One time we were out running and heading roughly northwest, I guess. We were in Thetford trail running—bush-whacking really—through this shin-high snow. We finally popped out by a deer-crossing sign in Norwich. We'd done about 20 miles, I guess, and the snow had wiped us out pretty good, so we just hitchhiked back into town." Such is "practice" for an elite distance runner.

In his junior year Kempainen broke Sapienza's record over Dartmouth's cross-country trail, which winds through the golf course. (The guy you saw flitting by as you were lining up that crucial chip to the 17th green, circa 1987: that might have been Kempainen.) In his final NCAA cross-country championships he finished 11th among the nation's 179 best woodland runners. In his final Heptagonals he helped Dartmouth score 149 points, the most in the meet's history, by winning the 10,000-meter run.

Even while he was setting new Dartmouth running standards, he was establishing academic marks of equal caliber. A biochemistry major, he maintained a G.P.A. in the high threes throughout his career, graduated summa cum laude, was named Academic All America, and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. (Typically, he was invisible during his Phi Bete initiation: He was off winning a race.) Such a person—distance running his game, biocem his course, doctoring his aim—must have been a nerd in extremis, right? kempainen answers the charge: "My life at Dartmouth was pretty structured, but still fun. Weekdays were busy. I studied pretty hard all week long, and then on weekends I'd do nothing. It was never like I had this broad, encompassing social life. Being in a three-season sport, my best friends were the guys on the team. On Saturdays we wouldn't necessarily go to the football game. We'd run, and then go sit up on the roof of South Fayerweather with a couple of beers, and just kind of take in the day. I liked that. I guess you could say mine was a Dartmouth experience within certain confines. I look back through my class book and realize I know very few of my classmates. But I did enjoy it up there, and if I had it to do over, I'd go back."

HE DID GO BACK, IN 1991 AND '92, WHEN HE took leave from Minnesota Med to train with Lananna for the U.S. Olympic marathon trials and, once he had cleared that hurdle, the Barcelona Games themselves. "I think I enjoyed that period even more than being a student," he says. "I worked in the lab sometimes—about 35 hours a week, I guess—but I didn't have the big corseload I lived over in Norwich, right on the river in that Rope Ferry carriage house. Ran every day on the Vermont side of the river. I got in about 75, 100, 110 miles a week. That was a terrific time." He was in one of those brief, carefree periods that everyone should experience: a pancakes-and-spaghetti, unmadebed, need-a-haircut, need-a-shave life. The healthful behavior and relaxed pace were required, for Kempainen was trying to find the answer to physical ailments both chronic and new. Chronically, he suffers from exercise-induced asthma, which is a gross thing to suffer from. "What happens is, if you're allergic—and for whatever reasons, I'm sensitive to ragweed—the smooth muscle along the airways clamps down when you exercise, and you start producing all this mucus. Not to be too graphic, but I've had runs where I'm constantly draining stuff out of my head. There'd be runs where..."

Okay, let's go on to the stress fracture.

"In December of '91 I had a stress fracture in my right knee, and then I got walking pneumonia and, probably because I was favoring the knee, I developed problems with my left leg. By the time of the trials in April [of '92] I wasn't even sure I wanted to run." But Kempainen did toe the line at the U.S. men's Olympic marathon trials in Columbus, Ohio, armed with a strategy developed in concert with Lananna. "It was only my second marathon," Kempainen remembers. "We knew there were veterans in the race, two guys in particular. I wasn't going to do anything they weren't going to do." While a few bold youngsters shot off the front of the pack, Kempainen fell in behind Steve Spence and Ed Eyestone. Once the rabbity kids had shot their wad, Kempainen finished where he had started: 11 seconds behind Spence and three behind Eyestone, good enough for the third and final ticket to Barcelona. There, on a hot (77 degrees) and humid (72 percent) midsummer's evening, he finished mere seconds behind Spence and Eyestone again, placing 17th in 2:15:54. "I had thought 2:15 would be right in the thick of it," he says. "When I looked at my place I wasn't too happy at first. But then I realized I was only a minute and a half out of thirdan Olympic bronze medal. Sometimes you can find things, indicators, that aren't obvious at first, but that really let you know you're making-progress."

Had more track watchers been paying attention to such clues, Kempainen's breakthrough in New York might not have come as such a surprise. "A real predictor for marathon success is cross-country results," says Merrell Noden, a former miler who has covered running for Sports Illustrated for a decade. "Bill Rodgers came from nowhere to place fourth in the world cross-country championships one year, then won his first Boston the next. Carlos Lopes was a cross-country champion and then won the Los Angeles Olympics marathon in what some people considered a big upset. That's the way it often goes. With Bob, people were looking at his 10,000 times and seeing him a full minute slower than the best. But clearly he was terrific over terrain. If they had remembered what he had done in 1990 in the very same city, the folks in New York wouldn't have been shocked at all."

On the morning of November 24, 1990, Kempainen, then a first-year med school student, had tried to read a textbook in his New York hotel room. "Relatively ineffective studying," he remembers. For that morning, his mind was on other things, specifically the 6.2-mile cross-country course up in Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx, where he was to run that afternoon in the national cross-country championships. Kempainen had finished second and then third in this event in the previous two years, races won by Pat Porter, who had triumphed in the event an astonishing eight years in a row. This day, however, Kempainen was on his game and Porter just slightly off. Four miles in, Kempainen buried the champ on Cemetery Hill and eventually built a 12-second advantage, winning in 30:23.

"In a marathon," says Noden, "you should always pay attention to a national cross-country champion."

And in the Boston Marathon, they always do pay attention to a man who has recently come in second at New York. That is why Kempainen, in Boston, has a room of his own and many demands on his time as the start draws nearer. Nevertheless, this courteous young man seems to have all the time in the world to talk about his life and marathoning with his visitor. Which is me. I, at this point, am just about out of questions.

"Did you run New York?" Kempainen asks politely, turning the attention from himself.

"Well," I answer sheepishly. "Run is a pretty strong word." "Have you run Boston?"

"Yeah, actually—a fewyears back. It was fun. There's this brass band at the first mile, and people along the whole route. A guy was running with a buffalo head on, and another guy carried a tree the whole way The women at Wellesley are amazing, they cheer so loud. And they give everyone kisses and..." Suddenly it comes to me that Kempainen might not be all that interested in what a 3:52:40 marathon looks like along the winding way; I figure he has other goals in mind. Sol shut up. Then I figure, on second thought, I'll ask him something I've always wanted to know myself: "Hey, actually, I was wondering: Do people who run like you see all that stuff? The crowd and the Wellesley women and all?"

"I tend to see just the most obnoxious or strongest stimuli, " Kempainen answers. "Sometimes the noise, like in Central Park—it's so loud and it just sort of becomes white noise. It's wild. You float along on it. And I remember in that race a classmate of mine from Dartmouth, Andy Paulsen, was biking ahead of me for a ways in Brooklyn. It was neat to see him, and it got me pumped up."

"Do these races go by fast for you?" I ask. "I mean, for the rest of us, well, they can seem like a death march." "Actually, yeah, they do go by pretty fast. The first 13 or 15 miles especially, if you're feeling good, they're over before you know it. Then things can get a little tight. But really, it's a pretty quick couple of hours. I'm usually not feeling too hot by 22,23 miles, but at that point other factors take over. The race itself, the finish."

"After your New York finish, Coach Lananna said he thought you were capable of a two-oh-nine."

"Well," says Kempainen, smiling slightly. "We'll see."

ON MONDAY, APRIL 18, WE DO SEE.IT IS A bright, crisp, cool morning as 9,000 runners gather on the green in Hopkinton, 26.2 miles west of Copley Square. The wind is gusting up to 20 miles per hour west to east, and it's nothing short of a perfect day for marathoning

Since we left Kempainen back at the Hancock Center he has enjoyed some socializing, some reflection, some strategizing Two nights before the race he gathered with some old College running buddies in Dorchester, at the house of John McWright '87. Frank Powers '86, Tim Clark '88, and Brian Lanahan '89 all wished Bob the best. L.J. Briggs '86 and Bob Reeds '89 traded good wishes with Kempainen; they too were entered in the race. Kempainen, as is his habit at the big events, skipped the formal pasta parties sponsored by race organizers. He prefers smaller, more relaxing functions.

On Sunday he talked through his game plan with Lananna, who had arrived in Boston on a red-eye from Los Angeles. Lananna left Dartmouth for Stanford in 1992, and had coached at a meet that Saturday at the University of Southern California. He still handles Kempainen and a couple of other post-grad distance runners. Kempainen is his star pupil.

And now it is Monday morning, and Kempainen is in the front row. The wheelchair runners have already left, and suddenly the gun sounds and the sneakered throng is off, starting its lemminglike journey toward the Atlantic. All of the top runners get out quickly, as they must. They zoom down the slopes of East Hopkinton and blaze past that brass band by the side of the road. Kempainen doesn't notice what tune is being played. The guy with the buffalo head is behind him somewhere, already a mile distant and a million miles from his thoughts.

Brandy still has the lead at the half, and retains it in Wellesley, 15 miles along. Kempainen is with the pack, and hasn't made an appearance on the top-ten tick sheet. He is unconcerned. "Personally, I was hoping I'd go out at the pace I did. I was surprised there was that big a pack. We tended to stick together and run as a group. I think people were saving it."

Brantly has spent it. Once he hits Heartbreak Hill—actually, a series of steep rises continuing over several miles from Wellesley into Newton—he's cooked. Lucketz Swartbooi of Namibia has the lead at the summit. Here the runners start to realize something: Only Brantly who will eventually finish 20th, is dropping back. The day is too good. As the pack breaks up and runners make their moves, the situation is antithetical to what occurred in New York: Boston's leaders are getting faster, not slower, in the 22 nd, 23rd, 24th, and 25th miles. It's a free-for-all to the finish. "It was weird," Kempainen will recall later. "I thought I was flying, but not enough people were coming back. It was so weird. I was flying, but I wasn't getting any closer."

Not true. With a mile left, he scorches Kenmore Square and Commonwealth Avenue, picking off top-ten runners for the first time this day. He catches two Kenyans and moves into eighth place. Surging toward Copley Square, he says good-bye to Swartbooi Cosmas Ndeti has just finished first a minute and a half ago, just four seconds ahead of Kempainen's old New York pal Espinosa, as Kempainen reaches the line in seventh place. He looks up at the clock and sees 2:08:47, by far his best. He's stunned. Friends shout to him that he has set the all-time Boston record for an American, that he has beaten Alberto Salazar's 1982 time and all those great times Bill Rodgers recorded in winning this race, and Kempainen can only walk forward, dazed, saying over and over: "I can't believe I ran this fast, I can't believe I ran this fast, I can't believe I ran this fast...and only finished seventh."

A WORD TO SPORTS FANS: CATCH KEMPAINEN now, if you can, for you have only three more years to see him run. At that time he will retire from marathoning voluntarily reducing himself to Dr. Bob. "That's the plan right now," he says. "I know what they say, that a lot of the best marathoners peak in their 30s. But I just can't imagine training properly when I'm interning. I do want to get on with my medical career."

What might happen between now and the time Kempainen hangs up his Nikes? Anything is possible, says an expert. "He's one notch away from winning something like Boston or New York," says Sports Illustrated's Noden. "He could move up that notch in a year or two. He has several things going for him. First, as opposed to the common theory, I think his medical schooling might actually help his running. For a guy as disciplined as he clearly is, he'll find the time to fit the training in. Mean- while, the distractions of medicine won't allow him to over-train. A lot of guys find it's really a pain in the neck to be a full time runner. He won't burn out like that. And he's not going to ruin himself on the roads: He knows he's going to be a doctor, and so he doesn't have to go out and chase a lot of money on the road to pay the rent.

"He'll run a couple of races each year, and you're going to see him do well in every race he enters. The clear-eyed, sensible approach he takes to things will always pay off. He's kind of a phlegmatic guy, and his very careful preparation assures that he'll not be finishing 28th or 29th if he gets to the starting line at all.

"The Olympics could be pretty exciting next time around. I would find it hard to say that he'll be a favorite, but he just might medal. I can assure you that in Atlanta in '96 he'll be in that pack for 18,19 miles, just like he was in Boston. Now, a couple of those guys are going to hang on for medals. Kempainen could be one."

And if he does, that precious metal will probably wind up as a paperweight in the neurology department at the Hennepin County Medical Center. If a patient should chance to ask Dr. Bob what it is, this unassuming man will surely respond, "Oh, it's nothing."

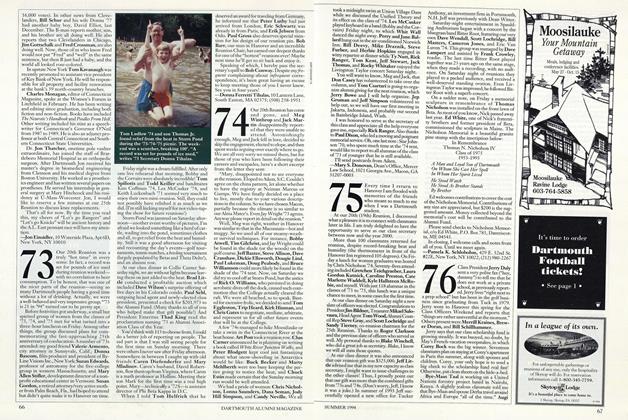

Arthur Roth (1916 winner) First Bostonian to win in Boston.

Clarence DeMar (1927) Won five out ofeight B.M.s.

Ellison Brown (1936) Indian nicknamed "Tarzan."

Tohn Kelley (1945) Running legend stillcomes out.

Leslie Pawson (1941) His third, win atage 37.

Bernard Smith (1942) This milkman wassick race morning.

Joan Benoit (1983) Outdoes mostmale winners.

Ambrose Burfoot (1968) First American towin in a decade.

Jack Fultz (1976) Temp was 91 inthe shade.

Bob Kempainen '88 (Seventh place 1994) Fastest Americanis still young.

But what is really impressive is that he does it in his spare time.

5 miles behind our Bob

4.8 miles

4.25 miles

3.8 miles

3.75 miles

3.2 miles

2.9 miles

2.5 miles

2 miles

FINISH

"The way Minnesota works, I played hockey inthe winter," says Kempainen.

"I can't believe I ran this fast," gasped Kempainen at the endof the Boston Marathon... "and only finished seventh."

Bob Kempainen '88 can cover 26.2 miles faster than any other American.

He crossed the line and found himself famous before the had dried.

He is the greatred-white-and-blue hope for American marathoning.

If They All Ran the Same Race... This graphic shows some ofthe 59 American winners ofthe Boston Marathon over its98-year history. If all of theserunners competed with Kempainen at their same winning pace —here is wherethey would be when Kempainen crossed the finish line.

An editor at Life magazine and a contributing editor for thismagazine, ROBERT SULLIVAN runs like Babe Ruth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

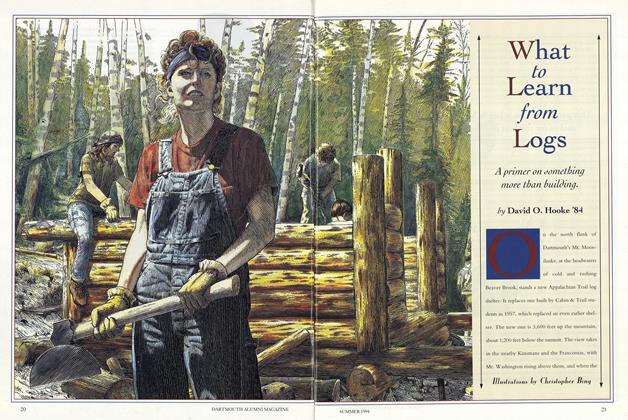

Cover StoryWhat To Learn From Logs

June 1994 By David O. Hooke '84 -

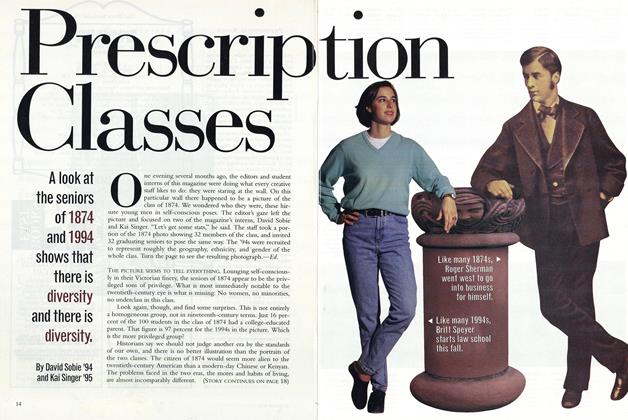

Article

ArticlePrescription Classes

June 1994 By David Sobie '94 and Kai Singer '95 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

June 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleFilling The Power Vacuum

June 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1973

June 1994 By Donna Ferretti Tihalas -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

June 1994 By Brooks Clark

Robert Sullivan '75

-

Sports

SportsFifty-one Minutes

May 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Real Story Behind the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club

SEPTEMBER 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

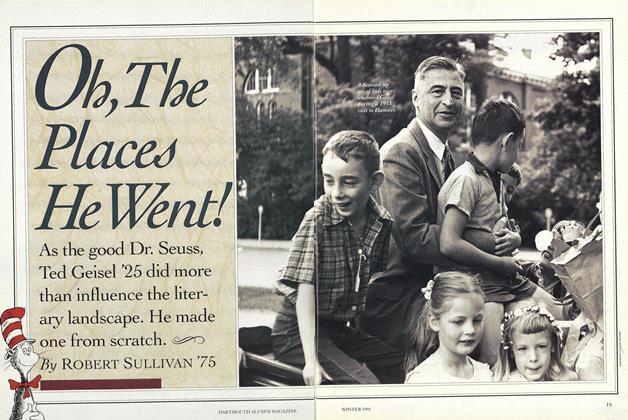

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleFootball From Down Under

December 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleDuke's World Revisited

June 1993 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

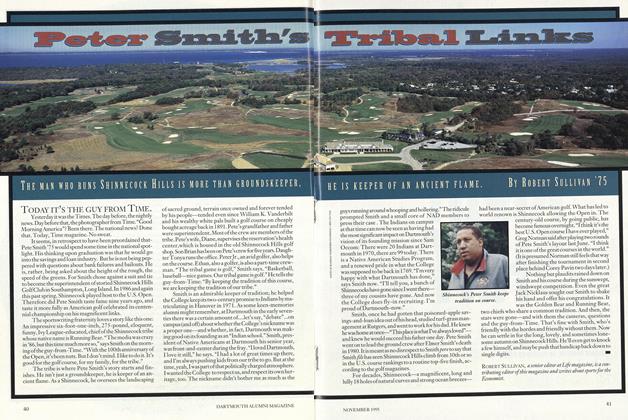

FeaturePeter Smith's Tribal Links

Novembr 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75

Features

-

Feature

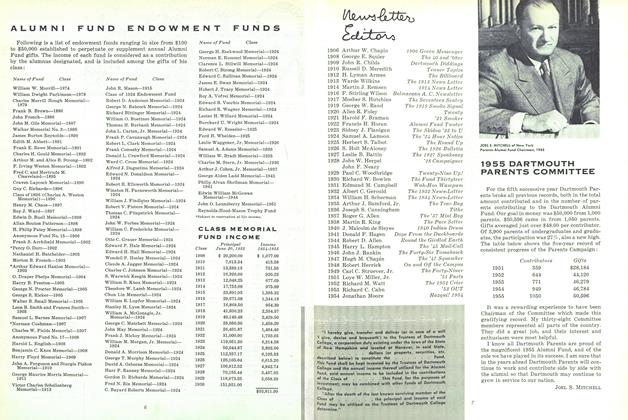

FeatureALUMNI FUND ENDOWMENT FUNDS

December 1955 -

Feature

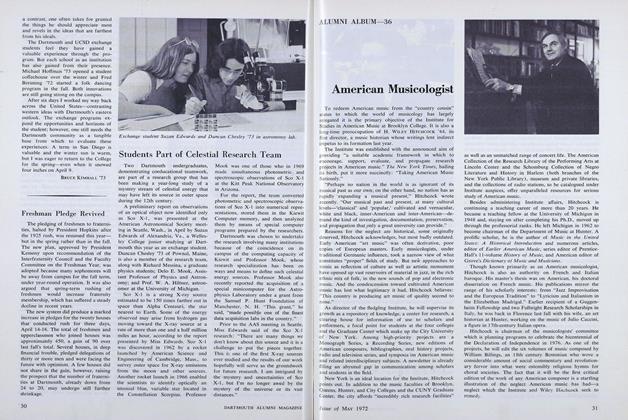

FeatureAmerican Musicologist

MAY 1972 -

Feature

FeatureHow to Win at Dartmouth

Jan/Feb 2006 By CAL NEWPORT ’04 -

Feature

FeatureAn Open Door Policy

July/August 2006 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureTHE SUBJECT IS GILROY

JUNE 1965 By RAYMOND BUCK '52 -

Feature

FeatureThe Second Emancipation

JULY 1963 By THE REV. JAMES H. ROBINSON, D.D. '63