Much of the world was caught off guard when the Iron Curtain disinte- grated. It wasn't so much the demise of com- munism that was shocking. What was—is—beyond many Americans' expectations is that totalitarian- ism has been replaced by dead- ly ethnic con- flicts. Seventy years of commu- nism, for all its rhetoric of com- mon purpose, had made no perma- nent dents in identities that were centuries deep.

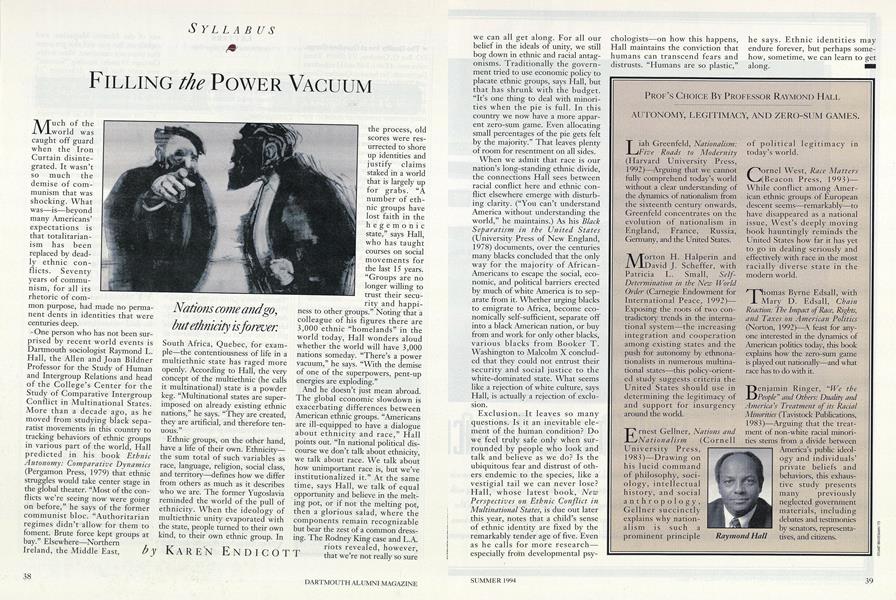

One person who has not been surprised by recent world events is Dartmouth sociologist Raymond L. Hall, the Allen and Joan Bildner Professor for the Study of Human and intergroup Relations and head of the College's Center for the Study of Comparative Intergroup Conflict in Multinational States. More than a decade ago, as he moved from studying black separatist movements in this country to tracking behaviors of ethnic groups in various part of the world, Hall predicted in his book EthnicAutonomy: Comparative Dynamics (Pergamon Press, 1979) that ethnic struggles would take center stage in the global theater. "Most of the conflicts we're seeing now were going on before," he says of the former communist bloc. "Authoritarian regimes didn't allow for them to foment. Brute force kept groups at bay." Elsewhere—Northern Ireland, the Middle East, South Africa, Quebec, for exam-ple—the contentiousness of life in a multiethnic state has raged more openly. According to Hall, the very concept of the multiethnic (he calls it multinational) state is a powder keg. "Multinational states are superimposed on already existing ethnic nations," he says. "They are created, they are artificial, and therefore tenuous."

Ethnic groups, on the other hand, have a life of their own. Ethnicity the sum total of such variables as race, language, religion, social class, and territory—defines how we differ from others as much as it describes who we are. The former Yugoslavia reminded the world of the pull of ethnicity. When the ideology of multiethnic unity evaporated with the state, people turned to their own kind, to their own ethnic group. In the process, old scores were resurrected to shore up identities and justify claims staked in a world that is largely up for grabs. "A number of ethnic groups have lost faith in the hegemonic state," says Hall, who has taught courses on social movements for the last 15 years. "Groups are no longer willing to trust their security and happiness to other groups." Noting that a colleague of his figures there are 3,000 ethnic "homelands" in the world today, Hall wonders aloud whether the world will have 3,000 nations someday. "There's a power vacuum," he says. "With the demise of one of the superpowers, pent-up energies are exploding."

And he doesn't just mean abroad. The global economic slowdown is exacerbating differences between American ethnic groups. "Americans are ill-equipped to have a dialogue about ethnicity and race," Hall points out. "In national political discourse we don't talk about ethnicity, we talk about race. We talk about how unimportant race is, but we've institutionalized it." At the same time, says Hall, we talk of equal opportunity and believe in the melting pot, or if not the melting pot, then a glorious salad, where the components remain recognizable but bear the zest of a common dressing. The Rodney King case and L.A. riots revealed, however, that we're not really so sure we can all get along. For all our belief in the ideals of unity, we still bog down in ethnic and racial antagonisms. Traditionally the government tried to use economic policy to placate ethnic groups, says Hall, but that has shrunk with the budget. "It's one thing to deal with minorities when the pie is full. In this country we now have a more apparent zero-sum game. Even allocating small percentages of the pie gets felt by the majority." That leaves plenty of room for resentment on all sides.

When we admit that race is our nation's long-standing ethnic divide, the connections Hall sees between racial conflict here and ethnic conflict elsewhere emerge with disturbing clarity. ("You can't understand America without understanding the world," he maintains.) As his BlackSeparatism in the United States (University Press of New England, 1978) documents, over the centuries many blacks concluded that the only way for the majority of African-Americans to escape the social, economic, and political barriers erected by much of white America is to separate from it. Whether urging blacks to emigrate to Africa, become economically self-sufficient, separate off into a black American nation, or buy from and work for only other blacks, various blacks from Booker T. Washington to Malcolm X concluded that they could not entrust their security and social justice to the white-dominated state. What seems like a rejection of white culture, says Hall, is actually a rejection of exclusion.

Exclusion. It leaves so many questions. Is it an inevitable element of the human condition? Do we feel truly safe only when surrounded by people who look and talk and believe as we do? Is the ubiquitous fear and distrust of others endemic to the species, like a vestigial tail we can never lose? Hall, whose latest book, NewPerspectives on Ethnic Conflict inMultinational States, is due out later this year, notes that a child's sense of ethnic identity are fixed by the remarkably tender age of five. Even as he calls for more research—especially from developmental psychologists-on how this happens, Hall maintains the conviction that humans can transcend fears and distrusts. "Humans are so plastic," he says. Ethnic identities may endure forever, but perhaps somehow, sometime, we can learn to get along.

Nations come and go,but ethnicity is forever.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Onlyness of a Long-Distance Runner

June 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

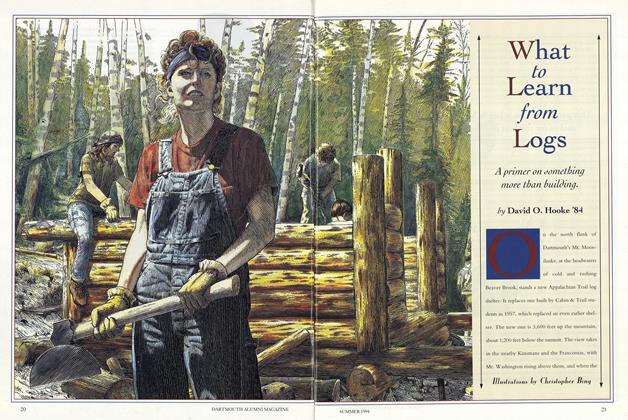

Cover StoryWhat To Learn From Logs

June 1994 By David O. Hooke '84 -

Article

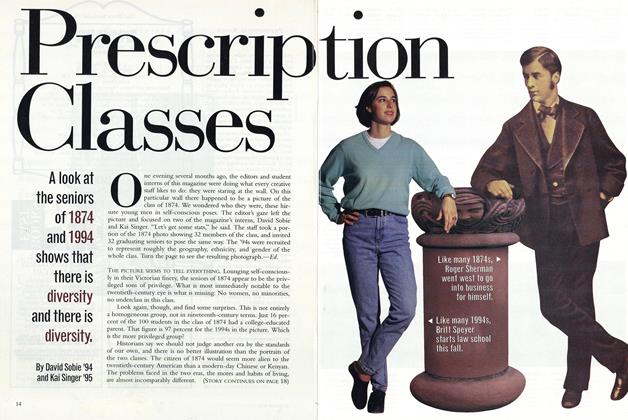

ArticlePrescription Classes

June 1994 By David Sobie '94 and Kai Singer '95 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

June 1994 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1973

June 1994 By Donna Ferretti Tihalas -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

June 1994 By Brooks Clark

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleArt in a Box

Winter 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleMemory and Catastrophe

June 1995 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMThe Answers Are Blowin’ in the Wind

Jan/Feb 2001 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMWhy the Play’s Still the Thing

May/June 2001 By Karen Endicott -

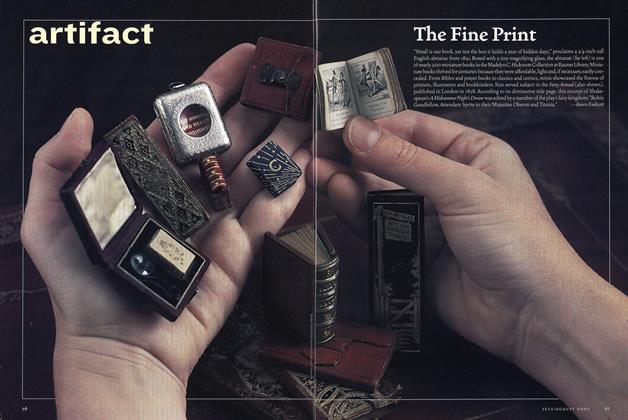

Article

ArticleThe Fine Print

July/Aug 2002 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleCONFRONTING CHEMOPHOBIA

December 1991 By Professor Gordon W. Gribble, Karen Endicott

Article

-

Article

ArticleNAVY-HANOVER RELATIONS CORDIAL, SURVEY DISCLOSES

January 1943 -

Article

ArticleCitation

May 1947 -

Article

ArticleRare Book Given

May 1948 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

February 1993 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

NOVEMBER 1962 By EDWARD S. BROWN JR. '34 -

Article

ArticleGreensleeves Plans An Alumni Issue

DECEMBER 1964 By RAYMOND J. BUCK JR. '52