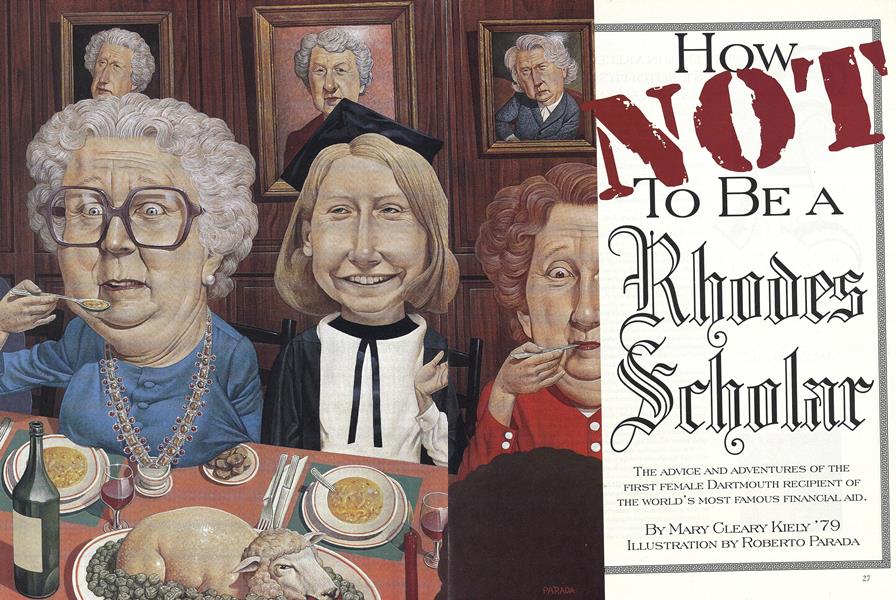

THE ADVICE AND ADVENTURES OF THE FIRST FEMALE DARTMOUTH RECIPIENT OF THE WORLD'S MOST FAMOUS FINANCIAL AID.

ADOOR OPENED IN A RECEPTION AREA IN THE ST. BOTOLPH'S CLUB IN BOSTON, AND THE SEVEN MEMBERS of the New England District Rhodes Scholarship selection committee filed in. "Okay," said the committee chair. "I'm going to try to make this as painless as Ink possible. I'm going to call out, in alphabetical order, the names of the four winners from our district for this year. As your name is called out, please stand. To the other eight of you, I can only say that I'm sorry." The only sound in the room was the hum of traffic from Common-wealth Avenue. "Cleary, Esty..." A pause. "Cleary!" I was still in my seat, clapping for what I was sure would be people other than myself.

I honestly hadn't expected to win. Yes, I had on my lucky shoes, and my mother had enlisted the saints on my behalf. But out of more than a thousand applicants from around the nation, only 32 could win. And like most applicants, I had heard my share of horror stories about what lay in store for me with the Rhodes selection committees. My personal favorite involved the applicant who was asked to open the window in a stuffy conference room, only to find it nailed shut.

In my case, however, most of the awkward moments in the selection process were of my own making. There was the first draft of my application essay, for example. For reasons unclear to me then or now, I had included a little anecdote about the death, by overfeeding, of some pet goldfish I'd had as a child. When I went to see my thesis advisor (and former Rhodes Scholar) John Boly to get his comments on the draft, Boly simply drummed his fingers on his desk and peered at me over his glasses. "Goldfish?" he said incredulously. "Goddamn goldfish gotta go!"

And then there was my rather dramatic entrance before the New Hampshire state selection committee. A few minutes before my eight a.m. interview was sched- uled to start, I rushed into the conference center dining area to grab a cup of coffee. The entire committee was gathered together having breakfast. "Hi!" I said and down I went, flat on my face in front of their table. After that, none of the questions that the committee members asked me not even my all-time favorite of "What has been your most profound thought?" had power to faze.

Last December, when Diana Sabot '95 became the 61st Dartmouth graduate to be awarded a Rhodes Scholarship, the event called up some memories, and even some advice of a sort. My first instinct was to tell her to be herself, only in my own case that same übiquitous and timeworn counsel proved rather disastrous.

So I thought that perhaps a few stories would be better, a kind of illustrated guide to how, well, how not to be a Rhodes Scholar.

FACING THE RUSKIN JEWELS

Somerville College principal Daphne Park was, by any standards, imposing. One of the first women to rise to a high rank in the British diplomatic corps, she possessed an "I've-got-your-number" kind of intelligence and a booming voice. Moreover, she had one of those large busts that made it impossible not to intrude on her space while within polite speaking distance.

On this particular occasion, soon after my arrival in Oxford, Miss Park's bust was bedecked with what the assembled gathering was informed were the "Ruskin jewels," gaudy Victorian pieces that had been bequeathed to the college some years before. She saw me staring at a particularly awful topaz item. "Miss Cleary," she intoned. "Welcome to Somerville College. After our sherry, we'll be having dinner together at high table [a raised dais in the dining hall] and, as a special honor, you will be seated at my left side." Over undercooked lamb and soggy Brussels sprouts, I was grilled about Dartmouth, my family, the Rhodes Scholarship. So far, so good.

Then Miss Park asked me what I thought of the dining hall, hung as is traditional in Oxford with enormous and somber portraits of former heads of college. Somerville had been founded as, and at that point remained, one of the few women's colleges in Oxford. So in contrast to the dining-hall hangings of most of the other colleges, the Somerville portraits were all of women. This, I thought, was a suitably safe distinction to remark on. I started to say that it was nice for a change to be surrounded by "musty old portraits of women," only that wasn't how it came out. Instead, to my dismay, I heard myself remark on the pleasures of sitting before "portraits of musty old women."

Miss Park's eyes bulged as she leaned over, her bust dangerously close to the remains of my roast potatoes. The topaz monstrosity, I noted, was already in a pool of mint sauce. "You do realize," she fumed, feigning calmness, "that I will be up there one of these days!"

Needless to say, I never again got that close to the Ruskin jewels.

Moral: Your mother was right. The only truly safe subject is the food.

FILTERED PHILOSOPHY

When she was feeling particularly agitated or when one of her students had said some thing particularly stupid, Oxford philosophy tutor Julie Jack would light a cigarette, using the space heater behind her desk. She would swivel her chair around and lean over, continuing to talk all the while. This exercise apparently required some skill and often took a number of tries.

I had noticed that Mrs. Jack tended to smoke a lot when I was around. When I was summoned to her office two weeks before my final exams exams that would determine which class of degree, if any, I would get I knew I was in trouble, for on her first pass at the space heater, Mrs. Jack actually lit the wrong end of her cigarette.

"You're going to fail!" she squealed as she went down for another try. "That practice exam you wrote was, was..." She glared at me. "What the hell were you doing, anyway, that term you were supposed to be reading general philosophy?

"Well," I offered weakly, "I got back a little late from Italy and then. I did do some reading but it was mostly, er, Iris Murdoch."

By now Mrs. Jack was chain-smoking. " I ought to have known you were reading fiction," she chortled, "because that's pretty much what you wrote on your exam."

"Perhaps I could do a little makeup reading?" I volunteered lamely.

"Two weeks before finals?" she shrieked. "No, I'll tell you what you re going to do You're going to go to the Encyclopedia of Philosophy and memorize the entries on Descartes, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. And God help you, because this year's questions are being set by one of the toughest examiners in the school!"

For the next two weeks I more or less slept next to the Encyclopedia. One of my fellow students, amused by my marching orders, even inserted orange page-markers that said "Reserved for Mary. Seriously." When exam day came, I used the allotted three hours to spew out absolutely everything I knew about the four philosophers. I even threw in a few jokes, figuring that no one else could possibly be desperate enoug to do the same.

Several weeks later, the exam results came out and once again I was summoned to Mrs. Jack's office. This time she was not smoking, which really got me worried.

"How bad was bad?" I mumbled, slumping into a chair.

"Bad, no!" she said, shaking her head in disbelief. "More like, say, miraculous.

Your exam paper got one of the highest grades in the university. There are only two possible explanations for this turn of events. Either what you wrote was so simple that it was perfectly clear; or your paper looked so different from everyone else's that the examiners thought you must be on to something!"

Before I left Oxford I gave Mrs. Jack a carton of cigarettes. And for myself I bought a copy of the Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Moral: Never underestimate the power of a few good jokes.

ORAL EXAM WITH LARGE FRIES

By Oxford standards it was a scorching summer's day, the limestone of the ancient buildings lit to gold but the air sticky and hot. I hurried down the High Street to the Examination Schools, an imposing edifice where I was scheduled for a viva, an oral defense of my written exam, to determine whether I was to be awarded a first-class or second-class degree.

The call notifying me of my appointment had come two days before, to a small village outside Oxford where I'd been staying with friends. After final exams I'd taken off for a week-long solitary hike across Dartmoor, in southwest England, a landscape of stark and craggy beauty populated mostly by miniature ponies and black-faced sheep and ancient stone circles. Philosophy and economics had been the last things on my mind.

I'd tried to bargain with my tutor over the phone "Can't I just take the second?" but she was adamant. So there I was, pacing outside the designated room, in the full academic dress required for all exams: black scholar's robe and cap, white blouse, black tie, black stockings, black shoes. I also reeked of mothballs, having previously stashed away my regalia for what I'd figured would be its next likely incarnation as costume-party garb.

One of the examiners appeared and asked me to follow him into a cavernous room. Twelve dons also in full academic dress from the School of Philosophy, Politics, and Economics were seated in a large semi-circle around a solitary chair. It was apparent from several twitching noses that they had noticed my smell.

"We'll be asking you a few questions today about labor economics," the head examiner said. "So please take a few minutes to re-read your responses in your blue book." He handed me the exam I had taken.

Not labor economics! I tried not to panic. On that particular exam I had run out of both time and inspiration in mid-sentence and, fatigued, had simply left it that way. The examiners assumed that I had more to say.

They asked me how tax policy could be used to influence unemployment, and I started to prattle on about the service economy and fast-food restaurants. One of the examiners leaned forward and said, sternly, "Of course you don't mean to suggest that you would like to see those golden, ugh, whatevers all over the English countryside, now do you?"

"Arches. Golden arches," I volunteered. "And, no, sir, I certainly didn't mean to suggest that!"

There was an exchange of looks among the examiners. A short time later, I was the proud new possessor of a second-class degree.

Moral: "Where's the beef?" is a question best kept to oneself.

FINAL ADVICE

I'm somewhat embarrassed to admit that Oxford's main thoroughfare now sports a McDonald's, though I swear I had nothing to do with that. I still indulge the travel bug that I caught while at Oxford, though now I carry credit cards and phrase books. At Dartmouth the knowledge that a lot of people had sacrificed to make the College possible for me—my parents and the nameless but not unthought-of donors who had provided scholarship aid translated into four rather driven years in which I slept remarkably little. While I don't regret the choices that I made while at Dartmouth,

How TO GET A RHODES

A few facts on the scholarship.

Cecil Rhodes a British-born colonial pioneer and statesman, established the Rhodes Scholarship in his will, to promote international understanding and peace. The first scholars went up to Oxford in 1904; to this day, the scholarship provides for two or three years of study there.

Currently, the annual distribution of the Rhodes Scholarships by country is as follows: United States 3-; Canada, 11 Australia, 9; South Africa 9; Germany, 4; India, 4; New Zealand, 3; Commonwealth Caribbean, 2; Kenya, 2; Zimbabwe, Bermuda 1 Hong Ron. 1; Jamaica, 1; Malaysia, 1; Pakistan, 1; Singapore, 1; Uganda, 1; and Zambia, 1. Malta also occasionally receives one scholarship. Since 1992, eight scholarships per year have been offered to members of the European Community, although that arrangement is der review by the Rhodes trustees.

Scholarship candidates must be unmarried; they must be at least 18 but not more than 24 years of age at the time of action; and they must have academic standing sufficient to ensure completion of a bachelor's degree before going up to Oxford. In gal changes in the United Kingdom permitted the Rhodes trustees to open the competition to women.

Mr: Rhodes's will specified that successful applicants are expected to show intellectual and academic quality of a high stand integrity of character interest in and respect for their fellow beings, the ability to lead, and the energy to use their talents to the While Mr. Rhodes felt that this energy was best demonstrated through success in sports, applicants are now allowed to show physical vigor in other ways.

Applicants are required to submit a college transcript, five to eight letters of recommendation, a statement of extracurricular acApplicants required to and other interests and one's reasons for wishing to study at Oxford, tivities and interests, ana a personal essay detailing one's academic and other interests and

A series of personal interviews is also involved. Colleges and universities generally make the first cut; in the committees composed of professors and administrators screen applicants from their respective candidates to didates on to the next round of competition. State-level selection committees invite a dozen to 20 of the most attractive candidates an interview Two of them go on for the final cut, at the district level. Out of the eight U.S. districts come four Rhodes Scholars.

All scholarship award are contingent upon the acceptance of Rhodes Scholars by Oxford colleges. Two samples of recent written work, approximately 2,000 words each, are required for college placement in all subjects other than the mathematical or the scientific.

the experience made my three Oxford years all the more, by contrast, like a gift of borrowed time.

A fellow Rhodes Scholar, unhappy at Oxford, confided to me once that she thought of the experience as one giant parenthesis in her life, an interruption m a career that she was eager to get on with. Oxford was a parenthesis for me, too, but it was as I have come to realize in the years since more like an ever-expanding one, embracing without constraining what came before and after.

I spent large amounts of time during my years in Oxford just thinking and talking: in long walks through Port Meadow, loved by Matthew Arnold; in frequent hiking jaunts through Europe; and in countless moments both solitary and communal at my own college, where such extraordinary women as Nobel Prize winner Dorothy Hodgkins, novelists Dorothy Sayers and Ins Murdoch, and former prime ministers Indira Gandhi and Margaret Thatcher once ate the same soggy toast. An I made friends: with other Rhodes Scholars; with English and foreign students at Somerville; with one of my philosophy tutors. And most of all with an Engish couple, who more or less made me their own. It is a friendship of the kind too rarely experienced, one of the great and serendipitous events of my life.

Serendipity that is what I wish for Diana Sabot as she settles into Oxford. An ability to find good things, even if by accident, is a pretty good passport to cany. Come to think of it, it's not bad equipment for life.

"Miss GLEARY, " SHE INTONED. "AS A SPECIAL HONOR, YOU WILL BE SEATED AT MY LEFT SIDE."

"PERHAPS I COULD DO A LITTLE MAKEUP READING?" I VOLUNTEERED LAMELY.

MARY CLEARY KIELY writes and raises two children in Weehawken, New Jersey.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryAn Insider's Guide to the World

October 1995 By Dawn Conner '95 -

Feature

FeatureEXCESS BAGGAGE

October 1995 By REGINA BARRECA '79 -

Feature

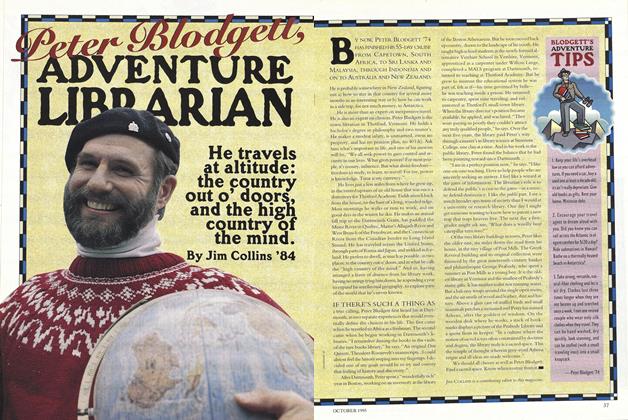

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

October 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleWhen Knowledge Cures

October 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWHAT the ELDERS WROTE

October 1995 By Karen Endicott

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNo Ordinary Joe

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2018 By EMILY ESFAHANI SMITH ’09 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHoney, They're HOME

January 1996 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79 -

Feature

Feature"Veni, Vidi, victus sum."

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Peter Smith -

Feature

FeatureC. Everett Koop '37 on Ray Nash

NOVEMBER 1991 By Ray Nash -

Feature

FeatureStudent Activism at Dartmouth

MAY 1966 By RICHARD A. BATHRICK '66 -

Feature

FeatureThe Past Is Prologue

JULY 1963 By T. DONALD CUNNINGHAM '13