This month's column is adapted from President Freedman 's speech for the recent dedication of the Barbara E. Rubin Building as the new home of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center's Norris Cotton Cancer Center.

HAVING MYSELF BEEN DIAGNOSED with cancer just over a year ago, and having only recently completed a six-month regimen of chemotherapy, I have developed a healthy interest in the ways in which our society deals with cancer. I have learned that cancer has always been not only a medical phenomenon, but a social, psychological, and cultural phenomenon, as well. There is a stern reality to the disease that extends beyond its biological reality, creating attitudes that affect our thinking about it, both individually and as a society.

Indeed, the fear of cancer as a near-certain death warrant has been a characteristic element in the history of medicine throughout much of this century, as has the disease's stigmatizing character. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the word "cancer" became the dominant disease metaphor for many social ills in urban and industrial life, much as tuberculosis had been the prevailing metaphor for alarming social conditions in the first half of the nineteenth century. It came to be used to designate specific phenomena that society feared or sought to condemn, from uncontrolled population growth to criminal practices such as political corruption. (We can all remember, for example, how John Dean told President Nixon in 1973, "We have a cancer within, close to the Presidency, that is growing. It is growing daily. It's compounded, growing geometrically now, because it compounds itself.")

This metaphorical use of the word "cancer" has hardly been desirable because, as Susan Sontag has written in her book Illness as Metaphor, as "long as a particular disease is treated as an evil, invincible predator, not just a disease, most people with cancer will indeed be demoralized by learning what disease they have."

Dr. Charles H. Mayo wrote in 1926, "While there are several diseases more destructive to life than cancer, none is more feared." Cancer has been a disease to be spoken of socially in the most hushed of tones, if at all. There was ever a sense that the mere act of naming cancer, as with other forces we dread and do not understand, was an act of devastation. For much of this century, few people would admit to the stigma of having cancer. Obituaries resolutely avoided mentioning the disease until perhaps 30 years ago, preferring to ascribe death, euphemistically, to a serious or extended illness.

Nowhere can the social change in attitudes toward cancer be seen more clearly than in the contrast between the secrecy that surrounded the treatment of President Cleveland for cancer of the mouth and jaw in 1893 and the openness that characterized the treatment of President Reagan for cancer of the colon in 1985.

Just as our attitudes toward cancer as a disease have changed during the course of this century, so too have the ways in which we treat cancer medically and surgically. For much of the late nineteenth century, cancer was regarded as a localized disease process and, therefore, one primarily within the province of surgeons. Eventually, however, physicians came to regard cancer as a collection of systemic diseases with local manifestations, and drew back sharply from reliance upon radical surgical procedures. This new approach heralded a more humane concern for the psychological well-being of patients, by recognizing that cancer was not merely a disease but also a state of mind. Today, oncologists and the manyother professionals concerned with identifying the causes of cancer and providing for its treatment are deeply engaged in exploring promising theories of genesis and metastasis that include diverse cell types, viruses, and oncogenes.

Research carried out at the Norris Cotton Cancer Center and the nation's 25 other comprehensive cancer centers has made great strides in enabling us to identify cancer at earlier stages in a very considerable number of patients, thereby increasing the chances of effective treatment. It has also made spectacular progress in understanding the genetic basis of cancer. And it has enabled us to counsel die avoidance of many dietary practices and environmental hazards associated with the onset of cancer. But last year, a number of the nation's leading scientific authorities on cancer told Congress that despite the expenditure of more than $23 billion since President Nixon committed the nation to a war on cancer in 1971, cancer was still on the rise, threatening soon to become the nation's leading cause of death. They asserted that half of all cancer patients could be cured if their tumors were discovered early enough. The experts called for universal access to state-of-the-art medical treatment, additional funding to move laboratory discoveries into clinical trials, and enlarged programs in cancer-prevention education.

Their message is especially important at a time when the budgets of federal agencies are threatened with reductions. If these reductions in funding do occur, they will diminish the capacity of the nation's cancer centers to carry forward the kind of basic research and clinical trials that have led to so many scientific advances in recent decades.

The Norris Cotton Cancer Center is an exemplar of the highest ideals of an academic medical center investigating scientific questions of immense medical and social importance, providing outstanding patient care to thousands of persons, and participating in the interdisciplinary search for greater understanding of one of the most resistant and enduring of diseases. And so, as we dedicate the Barbara E. Rubin Building of the Norris Cotton Cancer Center, I hope that our nation will rededicate itself to finding new understanding of the causes and treatment of cancer and fully supporting the scientific effort involved. The work is too important to us all to be permitted to falter or fail for lack of a national commitment.

We must not let the war on cancer falter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow not to Be a Rhodes Scholar

October 1995 By Mary Gleary Kiely '79 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAn Insider's Guide to the World

October 1995 By Dawn Conner '95 -

Feature

FeatureEXCESS BAGGAGE

October 1995 By REGINA BARRECA '79 -

Feature

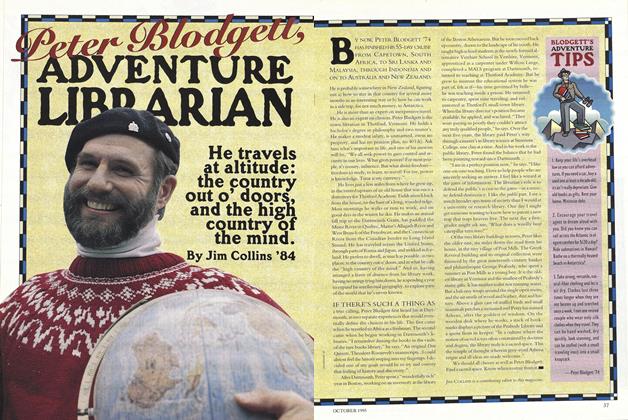

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

October 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleWHAT the ELDERS WROTE

October 1995 By Karen Endicott

James O. Freedman

-

Article

ArticleCOACHES AND PRESIDENTS

OCTOBER 1990 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleTHE PROFESSOR'S LIFE

FEBRUARY 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleON PERSONAL DISTINCTION

OCTOBER 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Word to The Able

December 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA New Dartmouth Tradition

June 1993 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Time Allotted Us

June 1994 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticleGifts of $291,988 Made In Past Six Months

April 1950 -

Article

ArticleIn Brief . . .

October 1959 -

Article

ArticleVisitors of Note.

JANUARY 1967 -

Article

ArticleArrivals and Departures

SEPTEMBER 1982 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

MAY 1972 By BLISS KIRBY THORNE '38 -

Article

ArticleTurning the Tables

Sept/Oct 2003 By Susan DuBois '05