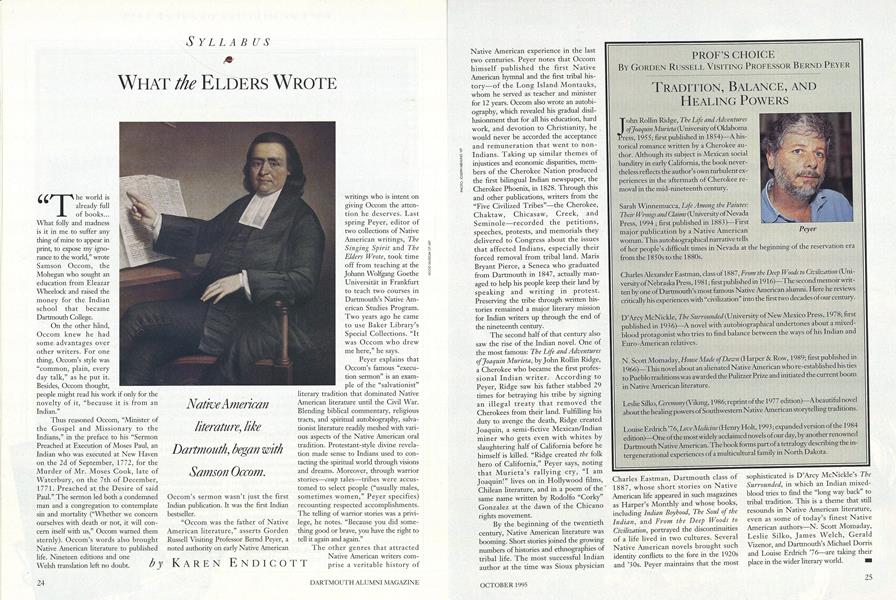

Best snow year: 1992-93 (76 inches total). "The world is already full of books... What folly and madness is it in me to suffer any thing of mine to appear in print, to expose my ignorance to the world," wrote Samson Occom, the Mohegan who sought an education from Eleazar Wheelock and raised the money for the Indian school that became Dartmouth College.

On the other hand, Occom knew he had some advantages over other writers. For one thing, Occom's style was "common, plain, every day talk," as he put it. Besides, Occom thought, people might read his work if only for die novelty of it, "because it is from an Indian."

Thus reasoned Occom, "Minister of the Gospel and Missionary to the Indians," in the preface to his "Sermon Preached at Execution of Moses Paul, an Indian who was executed at New Haven on the 2d of September, 1772, for the Murder of Mr. Moses Cook, late of Waterbury, on the 7th of December, 1771. Preached at the Desire of said Paul." The sermon led both a condemned man and a congregation to contemplate sin and mortality ("Whether we concern ourselves with death or not, it will concern itself with us," Occom warned them sternly). Occom's words also brought Native American literature to published life. Nineteen editions and one Welsh translation left no doubt.

Occom's sermon wasn't just the first Indian publication. It was the first Indian bestseller.

"Occom was the father of Native American literature," asserts Gorden Russell Visiting Professor Bernd Peyer, a noted authority on early Native American writings who is intent on giving Occom the attention he deserves. Last spring Peyer, editor of two collections of Native American writings, The Singing Spirit and The Elders Wrote, took time off from teaching at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universitat in Frankfurt to teach two courses in Dartmouth's Native American Studies Program. Two years ago he came to use Baker Library's Special Collections. "It was Occom who drew me here," he says.

Peyer explains that Occom's famous "execution sermon" is an example of the "Salvationist" literary tradition that dominated Native American literature until the Civil War. Blending biblical commentary, religious tracts, and spiritual autobiography, Salvationist literature readily meshed with various aspects of the Native American oral tradition. Protestant-style divine revelation made sense to Indians used to contacting the spiritual world through visions and dreams. Moreover, through warrior stories coup tales tribes were accustomed to select people ("usually males, sometimes women," Peyer specifies) recounting respected accomplishments. The telling of warrior stories was a privilege, he notes. "Because you did something good or brave, you have the right to tell it again and again."

The other genres that attracted Native American writers com- prise a veritable history of Native American experience in the last two centuries. Peyer notes that Occom himself published the first Native American hymnal and the first tribal history of the Long Island Montauks, whom he served as teacher and minister for 12 years. Occom also wrote an autobiography, which revealed his gradual disillusionment that for all his education, hard work, and devotion to Christianity, he would never be accorded the acceptance and remuneration that went to non-Indians. Taking up similar themes of injustices and economic disparities, members of the Cherokee Nation produced the first bilingual Indian newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, in 1828. Through this and other publications, writers from the "Five Civilized Tribes" the Cherokee, Chaktaw, Chicasaw, Creek, and Seminole recorded the petitions, speeches, protests, and memorials they delivered to Congress about the issues that affected Indians, especially their forced removal from tribal land. Maris Bryant Pierce, a Seneca who graduated from Dartmouth in 1847, actually managed to help his people keep their land by speaking and writing in protest. Preserving the tribe through written histories remained a major literary mission for Indian writers up through the end of the nineteenth century.

The second half of that century also saw the rise of the Indian novel. One of the most famous: The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta, by John Rollin Ridge, a Cherokee who became the first professional Indian writer. According to Peyer, Ridge saw his father stabbed 29 times for betraying his tribe by signing an illegal treaty that removed the Cherokees from their land. Fulfilling his duty to avenge the death, Ridge created Joaquin, a semi-fictive Mexican/Indian miner who gets even with whites by slaughtering half of California before he himself is killed. "Ridge created the folk hero of California," Peyer says, noting that Murieta's rallying cry, "I am Joaquin!" lives on in Hollywood films, Chilean literature, and in a poem of the same name written by Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzalez at the dawn of the Chicano rights movement.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Native American literature was booming. Short stories joined the growing numbers of histories and ethnographies of tribal life. The most successful Indian author at the time was Sioux physician Charles Eastman, Dartmouth class of 1887, whose short stories on Native American life appeared in such magazines as Harper's Monthly and whose books, including Indian Boyhood, The Soul of the Indian, and From the Deep Woods to Civilization, portrayed the discontinuities of a life lived in two cultures. Several Native American novels brought such identity conflicts to the fore in the 1920s and '30s. Peyer maintains that the most sophisticated is D'Arcy McNickle's The Surrounded, in which an Indian mixedblood tries to find the "long way back" to tribal tradition. This is a theme that still resounds in Native American literature, even as some of today's finest Native American authors N. Scott Momaday, Leslie Silko, James Welch, Gerald Vizenor, and Dartmouth's Michael Dorris and Louise Erdrich '76 are taking their place in the wider literary world.

Native American literature, like Dartmouth, began with Samson Occom.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow not to Be a Rhodes Scholar

October 1995 By Mary Gleary Kiely '79 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAn Insider's Guide to the World

October 1995 By Dawn Conner '95 -

Feature

FeatureEXCESS BAGGAGE

October 1995 By REGINA BARRECA '79 -

Feature

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Article

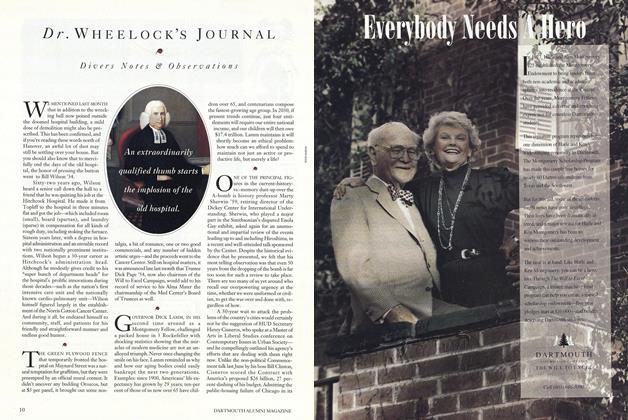

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

October 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleWhen Knowledge Cures

October 1995 By James O. Freedman

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleA Professor's Delights

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

June • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleOut of the Literary Closet

NOVEMBER 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleSound Words

FEBRUARY 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWHEN POETRY SPEAKS

FEBRUARY 1991 By Professor Cleopatra Mathis, Karen Endicott