WHAT COUNTS WHEN YOU TRAVEL IS LESS WHAT YOU GAIN THAN WHAT YOU LEAVE BEHIND.

I WROTE ABOUT MY FOOLISHNESS IN LEAVING HANOVER, ABOUT MY BELIEF THAT IF THERE WERE A FIRE IN THIS BUILDING A FIFTH-FLOOR DESCENT ONTO CONCRETE WAS MY ONLY FATE, ABOUT THE FACT THAT LONDON LOOKED ABOUT AS QUAINT AS FLATBUSH.

after my sophomore year, when I various religious paraphernalia to guarantee a safe trip. I had one or two rosaries, assorted rabbits' feet, notes of support, a lucky necklace, and a hard-cover copy of Gravity's Rainbow. Other wiser or more experienced students carried only sleeping bags and backpacks. We choose our own baggage, I have since learned, but I wasn't aware of that in 1977.

Along with the amulets, I carried the piece of paper from the Foreign Study office. There were cryptic, unsettling elements in this document. These included a list of suggested resources sent by the residence hall at University College, London, where I would be spending the next six months. One of the items indicated that I should pack a "travel rug" for the room. Travel rug? I thought maybe I was supposed to roll up a piece of Astroturf and drag it across the Atlantic. I had no idea that it meant I ought to bring a light blanket. I figured that I wouldn't need the suggested and mysterious "rucksack" because I didn't have a ruck on me. I was too embarrassed to ask what these words meant since they seemed selfexplanatory to everyone but me.

It's not like I thought I was going to the moon. After all, I knew people who had returned from London saymg things like "lift" instead of "elevator" and talking about girls with "ginger-coloured hair" (you could practically hear them add the silent "u") instead of redheads. One girl who lived next door to a pal in Wheeler went into raptures about "chocky-bickies" and another sang virtually orgasmic arias about the pleasures you could find by merely "chatting up" an Englishman. Clueless as I was about any exact translations of these terms, it all sounded good to me. I thought of myself standing on the very spot in the alley where Marlowe was stabbed to death, I loved the thought of going to the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre since these were places I'd actually heard of or researched in my studies as an English major. I wanted to see The Old Curiosity Shop. I pictured myself drinking tea and making charming conversation with my British betters. I thought of thatched cottages and gothic garrets. I thought of intimate yet high-powered seminars. I pictured myself as perfectly at ease.

Pictures lie. I hailed a cab after arriving at Victoria Station and was terrified when the driver rolled what I could only imagine was an enormous joint: he was certainly rolling something and I never knew anyone who actually made their own cigarettes. I thought Id get busted for being in this guy's cab, or that at the very least he would swerve into oncoming traffic because all the other cars were clearly being driven by women and dogs. I possessed the information, of course, that the driver's side was opposite from where we sensibly had it at home, but it was bizarre and unnerving to see it. When the cab deposited me at the hall of residence, I was panic stricken. It was a blank concrete building of at least 15 stories, and I was one of about three people in the place. I felt like Scrooge when he's left at school as a child because his father hates him.

I dragged my suitcases to the elevator, already wondering why on earth I'd brought books with me since I was only going to have to cart them back again. I was alone in an endlessly long hallway, and the first night there I wrote minute by minute in a notebook about my foolishness in leaving Hanover, about my belief that if there were a fire in this building a fifth-floor descent onto concrete was my only fate, about the fact that London looked about as quaint as Flatbush. It was also around 80 degrees outside and that damned piece of paper I'd carried with me had warned me about dressing too lightly. All I had with me were fisherman knit sweaters and long johns, along with other outfits I had packed in what was clearly a delirium: long skirts, Spandex tops (I thought maybe there were still discos), and glittering high heels. I heard people laughing from the street below and it struck me as unbelievably odd that for everybody else it was simply Tuesday night. I remember leaving the light on when I went to sleep.

Afraid that everybody I left at home would be either married or dead before I could make it back in March, I waited for mail as if I were a prisoner waiting for a pardon from the governor. When I didn't hear from him on the first day, I called my boyfriend collect. He was comforting. Figuring that what worked once would work twice, I called him an hour later. He was less comforting. When I called him a third time that day he told me that he couldn't afford my emotional life and suggested that I go to a movie. It was not what I wanted to hear. He told me that he was disappointed in my lack of independence and the loss of what he called my adventurous spirit. I didn't call again for a while. I wrote letters on blue airmail stationery that I had the good sense not to mail.

Classes at UCL would start at the beginning of the next week, and I knew that more students from Dartmouth would arrive over the weekend. I had decided to come early to London because I thought that after acclimating to Hanover I could make myself at home anywhere, figuring that I did indeed have an adventurous spirit, as long as I knew the territory. But I found I was out of my league on all levels when I went to buy myself a ham sandwich, expecting a version of the overstuffed Peter Christian's special. I was handed exactly one piece of flaccid ham between two slices of white bread smeared with butter. I bought grapes and they had seeds. I was forced to admit how spoiled I was. Other friends had spent time hiking through the rain forest, and one girl in our dorm had arrived fresh from spending three years in a small African village. Surely I could make it in a land that spoke my native tongue? Why was I so unprepared for the difference I found?

I decided to walk. I walked to the law courts and admired the buildings. I walked down the Strand and went into bookstores. I walked to St. Paul's and to the HMS Discovery and to Big Ben. At least I was thoroughly exhausted by the time I went back to Ramsey Hall and could sleep without wondering every 15 minutes what time it was "at home," and wondering what people were eating at Thayer Hall while I was eating Toad-in-the-Hole. (It would be a month before I discovered fish and chips.) During those first days I groped around as if I were exploring a dark cave, not realizing that I carried a light with me even though I had packed badly.

The fourth or fifth day there it poured for the first time since my arrival and that made me feel a little better; it was, after all, what I had expected all along. It was a foggy day in London town. Being a girl who knew her Cole Porter I figured that for me at least the British Museum would not have lost all its charm. A short walk down Tottenham Court Road', and I was immediately thrilled by the entrance to the museum because there was no admission price. Being told that I could just walk in made me feel welcome in an entirely new way. I knew about museums, and I immediately started searching for a place where I could buy a cup of coffee when I was stopped short by an illuminated manuscript of The Canterbury Tales.

Having studied Chaucer in one class or another, and especially having witnessed Alan Gaylord's recital of "The Miller's Tale" the year before, I was finally, wonderfully, and fully engaged by something outside myself. "Smalle birds Maken Melodye" I read, and my eyes filled with tears. This wasn't like anything I'd ever seen at home, not even from doing research with rare books or in the closed stacks. This was Something Else, with a his

Tory longer than I could imagine. People had looked at this manuscript before it became required reading, and now I was part of that history just by walking into this beautiful building for free. These luscious pages weren't hidden away in some small room for the exclusive and fetishistic gaze of senous scholars but were instead right there on the ground floor. I'd foundaplace of safety. If this manuscript could be safe here, then so could I.

But folded into those first few days was as much learning as anything that followed, even if it wasn't part of the curriculum, even if what was necessary a little courage, a little imagination, a little belief in the possibility of unforeseeable happiness hadn't been listed as suggested resources by the Study Abroad Program. It was good to be encouraged to leave Hanover as soon as it became too comfortable, and, like a good parent, the College knew as much.

I left London with less baggage than I had come with, and what I left behind was at least as important as what I took with me. I've heard the same stories from nearly everyone who went on a program enabling them to live elsewhere, even if that elsewhere was Jersey City. You learn that you carry the ability to make a life for yourself wherever you are. It is a lesson that should never be underestimated; it is one of the few lessons on which we are all tested again and again.

GINA BARRECA is a contributing editor of this magazine and a professor of English at the University of Connecticut in Storrs. Her latest book is Sweet Revenge: The Wicked Delights of Getting Even.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow not to Be a Rhodes Scholar

October 1995 By Mary Gleary Kiely '79 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAn Insider's Guide to the World

October 1995 By Dawn Conner '95 -

Feature

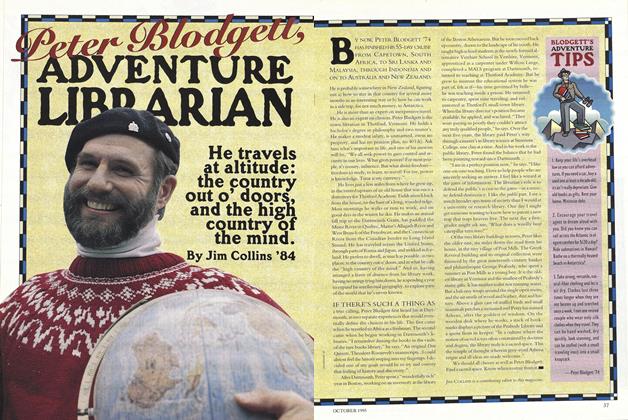

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

October 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleWhen Knowledge Cures

October 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleWHAT the ELDERS WROTE

October 1995 By Karen Endicott

REGINA BARRECA '79

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorWhither the Greeks?

MAY 1999 -

Feature

FeatureThey Used to Call Me Snow White... But I Drifted

June 1992 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureTau Iota Tau and Other Brassy Memories

FEBRUARY 1994 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureAfter Eleven Commencing

June 1995 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMater Dearest

MARCH 1997 By Regina Barreca '79 -

Feature

FeatureAfter the FALL

JANUARY 1998 By Regina Barreca '79

Features

-

Feature

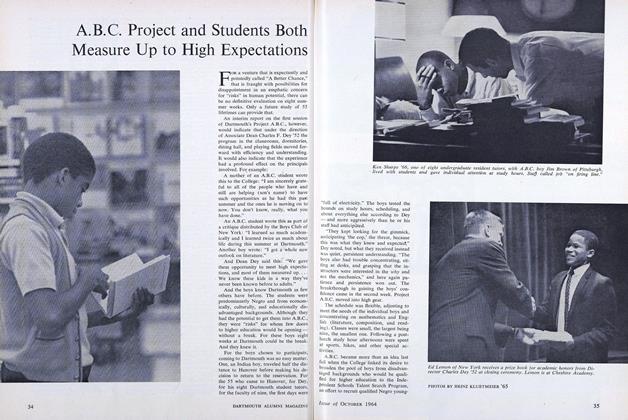

FeatureA.B.C. Project and Students Both Measure Up to High Expectations

OCTOBER 1964 -

Feature

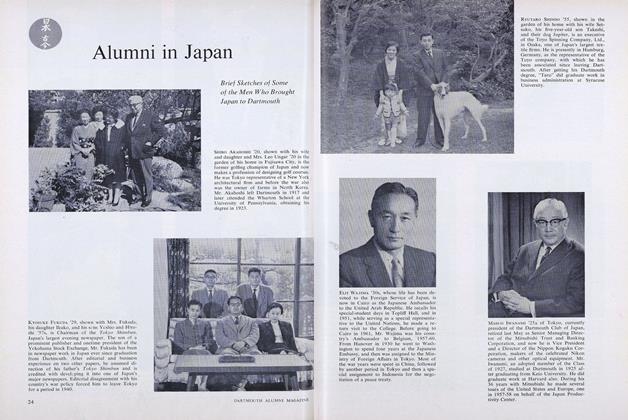

FeatureAlumni in Japan

MARCH 1965 -

Feature

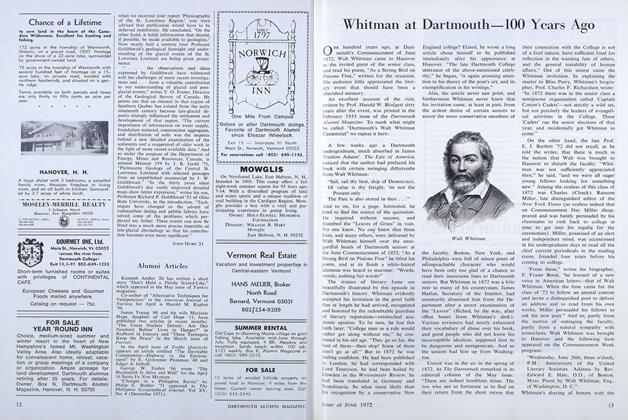

FeatureWhitman at Dartmouth—100 Years Ago

JUNE 1972 -

Feature

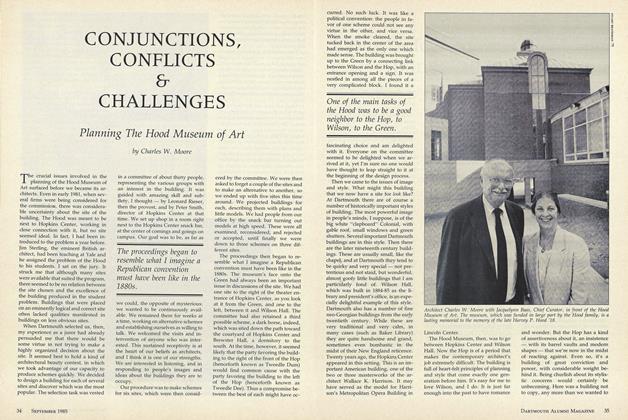

FeatureCONJUNCTIONS, CONFLICTS & CHALLENGES

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Charles W. Moore -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Chief Retires This Month

JUNE 1966 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

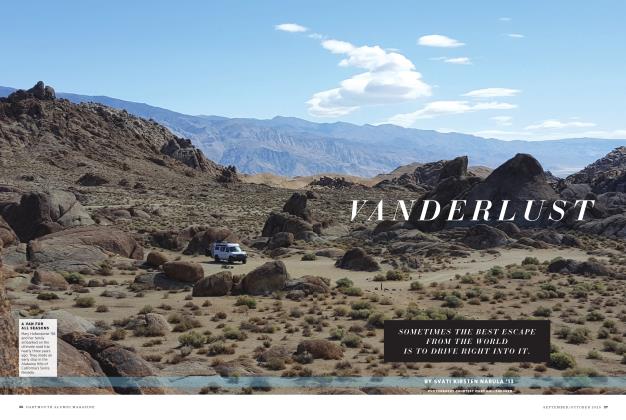

Cover StoryVanderlust

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2020 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13