You walk into Psychology Professor Todd Heatherton's lab to help with a study on perception and he hands you a milkshake. Dutifully, you drink it. Then Heatherton asks you to taste some ice cream and rate its sweetness, bitterness, and texture. When you're done, he leaves, saying, "Feel free to help yourself to the leftover ice cream."

What do you do?

If you're a dieter, you'll probably eat lots of ice cream. After all, you've already "blown the diet. If you're not dieting, you're likely to leave without eating much more. After all, you've already had a milkshake.

Heatherton is trying to understand how people control their behaviors and what happens when they fail. ("If I cause dieters to fail a test, they'll eat more," he notes.) In addition to studying dieting problems, he analyzes a host of -isms and disorders—alcoholism, bulimia, and compulsive gambling, to name just a few—as failures of self-regulation. Heatherton shares the results of his studies with students in a seminar on Appetites and Impulses and a course on Self-Regulation of Behavior.

The idea that people are able to control their own behaviors lies at society's philosophical and legal heart. Yet, Heatherton explains, the most commonly accepted explanations of problematic behaviors essentially divorce the person from the action. Freud theorized that unconscious forces beyond our control determine much of human behavior. Behaviorists countered Freud with the theory that a person's history of rewards and punishments sets behavior. Currently popular physiological explanations reduce behavior to the workings of neurons and cravings of genes. All three theories view behavior as the product of external or uncontrollable forces. The social fallout, however unintended, is clear on talk shows, front pages, and in courtrooms across the nation, as people blame behavioral problems on irresistible impulses, television violence, bad memories, or raging hormones. "We've become a society of victims," says Heatherton.

Self-regulation theory puts conscious choice back into the picture. While recognizing physiological, learning, and developmental dimensions of human behavior, Heatherton, a co-author of Losing Control:How and Why People Fail at SelfRegulation, contends that people are capable of altering their own responses, including thoughts, feelings, actions, and desires. To be sure, sometimes people fail, but even failure involves some degree of conscious choice. "It's like viewing the person as a canoeist heading down white water," Heatherton explains. "There are forces—rocks, currents—that influence your course. But at the same time paddling alters your course. You can speed up or slow down."

Take alcoholism. .Most people believe that alcoholics cannot control their own drinking. "But that's not true. People can and often do control it," he says. "Although physiological addiction and learned cravings are powerful determinants of the urge to drink, alcoholics do have some control over when and how much they drink." Yes, alcoholism is influenced by genes, but "a gene doesn't reach out and drink the drink for you." Heatherton takes issue with defining alcoholism as an illness. As he puts it, "Addiction is not the same thing as a disease."

What, then, explains why people give in to problem drinking, eating, spending, infidelity, and other human temptations? The greatest determinant of self-regulatory failure is a person's emotional state, says Heatherton. As anyone trying to cut back on cigarettes knows, being worried or upset makes lighting up seem irresistible. "When you're stressed, physiology kicks in, but you still have to go somewhere to get the cigarettes to indulge the habit," he says. "Simple physiological or learning explanations fail to capture the extent to which people are unwitting accomplices to their own indulgences." But, he qualifies, "Self-control is often difficult and sometimes physiology overwhelms it."

Self-regulation theory recognizes that self-control takes effort, both physiological and emotional. And effort in turn takes a certain kind of strength. Heatherton maintains that people can build up self-control by exercising it, much as routine gym workouts build physical strength. But the analogy comes with a caveat: just as muscles can become fatigued, so can self-control. Moreover, as people try to control one domain in their lives, they may lose control over other, weaker areas.

When people focus on goals—and can see the reward—they find it easier to stick to helpful behaviors, Heatherton says. "Giving people goals sounds trite, but it works" he maintains. Another way to control behavior is to transcend emotional responses. "Taking control means developing workable strategies that conquer those negative emotions," he says. For many people, old tricks suffice: counting to ten, thinking before speaking, and taking time to cool off. For others, the solutions are not so simple. In fact, Heatherton is currently studying why some people try to escape their emotions and troubles by indulging in the very behaviors that can only make matters worse, like the dieter who responds to anxiety by binge eating.

For people struggling with their own problems of self-control, Heatherton offers a last piece of advice: "Don't regard a minor lapse in self-control as a relapse."

A milkshake, after all, is just a milkshake. m

When it comes toself-control,or lose it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMoments of Peace

December 1995 By Stephen Madden -

Feature

FeatureNice Work if You Can Get It

December 1995 By DIANE CYR -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND REMEMBRANCE

December 1995 By James Wright -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticlePreparing for Contingencies

December 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

December 1995 By Armanda Iorio

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleA Professor's Delights

MAY • 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

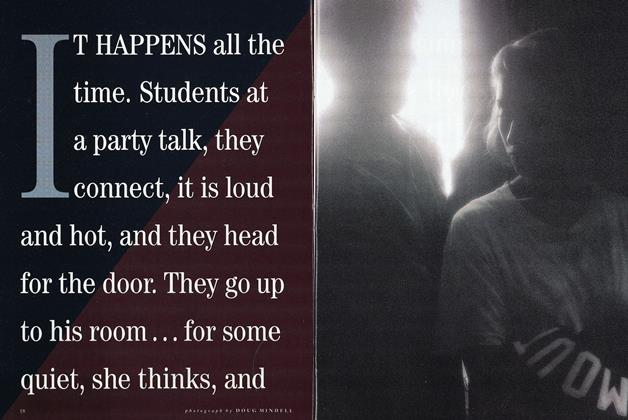

Cover StoryThen lings get ugly

NOVEMBER 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleWhy the Novel Matters

May 1994 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

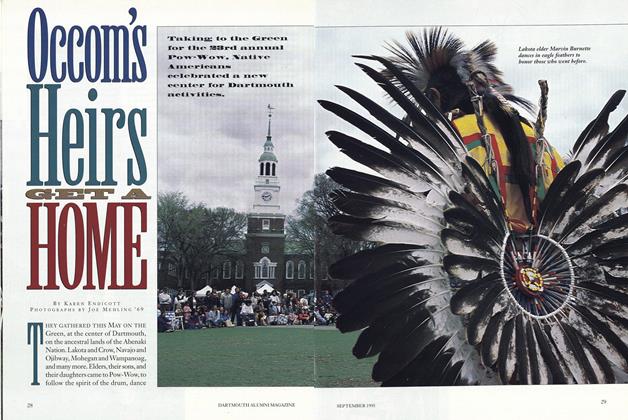

FeatureOccom's Heirs Get a Home

September 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

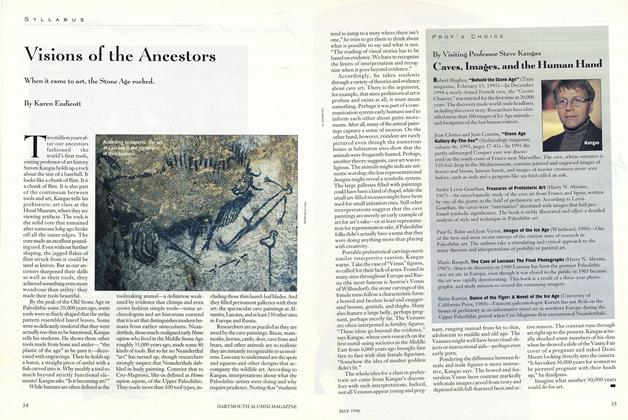

ArticleVisions of the Ancestors

MAY 1996 By Karen Endicott -

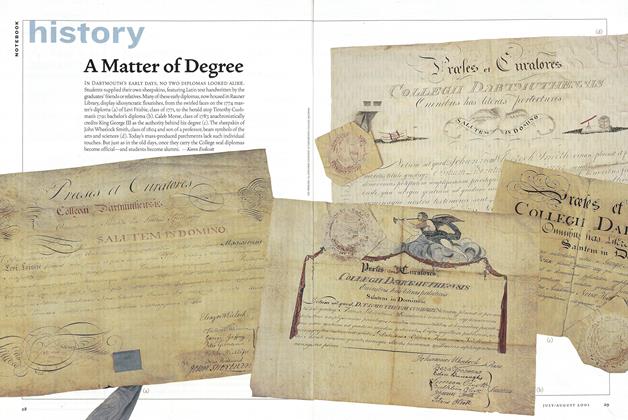

HISTORY

HISTORYA Matter of Degree

July/August 2001 By Karen Endicott