This month's Presidential Range is an adaptation of President Freedman's September 20 speech at Dartmouth's 226th Convocation.

This convocation is an occasion for considering one of the important issues that a liberal education helps each of us to address: What are our goals in life and how do we best go about achieving them?

The task of identifying and then pursuing one's aspirations is made more difficult by the tangled skeins of effort and coincidence, design and chance, that will govern the ways in which each of us works out his or her destiny during the years ahead.

Life is shaped by contingencies we cannot predict. They simply happen, sometimes providing us serendipitously with sublime satisfaction, sometimes condemning us indiscriminately to awful pain. We cannot know what boon or bane the future holds. Yet each of us, wary of fate, wants to believe that we can set a reliable course for the future. We yearn for—we dearly need— a sense of control over our own destinies. We strive to reduce the likelihood of uncertainty by leading our lives in ways that seem most likely to assure the outcomes we want. We cling to the strict belief that hard work will be rewarded and that the universe is indeed just.

The most effective protection against the contingencies of experience are values that appeal to our very best natures and anchor us most securely in the churning ocean of fate. Foremost among those values is idealism.

In talking with students over the years, I have been struck by how many desire to identify with role models by whom they might be guided and inspired—men and women whose conduct of their lives is commensurate, morally and intellectually, with their own most selfless aspirations.

If your life's goal is to make a buck, or to accumulate trinkets and stock certificates, or to peddle advertisements for yourself, then role models abound. But the grey and uninspired existence that they propose, the meretricious goals that they seek, cannot be what the glory of a liberal education is about. Surely life and liberal learning mean more than that.

As you look for appropriate role models, you can not do better than to emulate men and women who are idealists. Who are idealists? They are people who are inspired by an idea greater than themselves, who are driven by a moral imperative to imagine a world better than the one they found. They are people animated by principle, who dedicate their lives to fortifying the spirit and improving the lot of those on the brink of hopelessness. They are people who sail against the wind and persevere despite setbacks or ambiguous success.

Idealists are informed on political matters and involved in the civic life of their communities. They devote their energies to the debates that make wise and humane public policy, as all Athens did in the age of Pericles.

Idealists care about those who need help and commit to national service and to a life-time of civic engagement. They care about the health and well-being of neighbors and strangers alike. They care about the legal rights of all, especially those without advocates. They care about the working poor who struggle to make their way and to preserve their families in a global economy of bewildering technological change. They care about children, who need the full support of society in order to achieve their potential.

Idealists remind us, by the way in which they advance the lives of others, that, as Matthew Arnold said, "Life is not a having and a getting, but a being and a becoming." And they invite us, through their generosity, to be open to the possibility that what they have been for us, we might be for others.

Idealists are not mere dreamers. They are known by their deeds and by the pride and purpose that animate their altruism. They instruct us, by their example, in the best meaning of character. Idealists are not rare. But there are not enough of them, in this society or any other.

I have the feeling that many of us regard life as beginning, in an important sense, only after we pass some future milestone—after we have been graduated from college, after we have settled into a prestigious job or a comfortable home or a proper marriage, after we have achieved a measure of professional success or personal security. It is only then—several decades into middle age—that many people finally give themselves permission to live generously.

But life, of course, is what we are doing now. And so the necessity of leading a life guided by ideals, a life that each of us is proud to lead, is present from the start and is always there. My message is that a life motivated by idealism promises the deepest kind of personal satisfaction.

As you pursue your liberal education at Dartmouth, I hope that you will give yourself over to idealism, for your own sake and for that of society. I hope that you will take nourishment from this commonwealth of liberal learning and that each of you, through the efforts of a lifetime, will help move us all toward a more just and humane society.

Idealismis our best anchor inthe ocean of fate.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

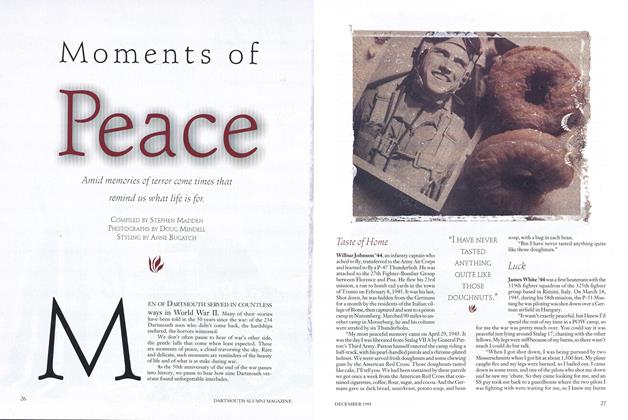

Cover StoryMoments of Peace

December 1995 By Stephen Madden -

Feature

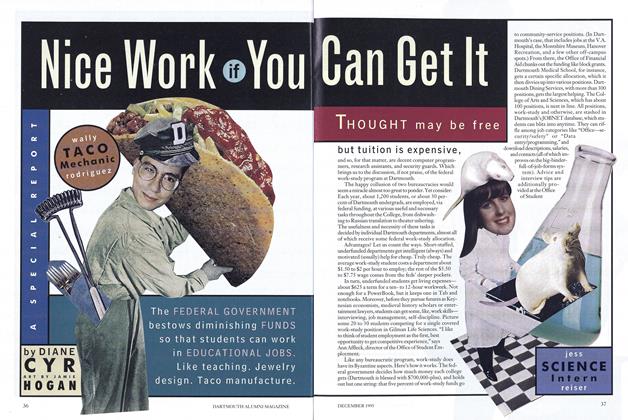

FeatureNice Work if You Can Get It

December 1995 By DIANE CYR -

Feature

FeatureWAR AND REMEMBRANCE

December 1995 By James Wright -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1995 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleControlling Self-Control

December 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

December 1995 By Armanda Iorio

James O. Freedman

-

Article

ArticleORIGINALS AND COPIES

JUNE 1991 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Trembling Hope

APRIL 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleCompared to What

June 1992 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleA Comprehensive Overhaul

October 1992 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleObligations of the Educated

September 1995 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleA Quiet Greatness

DECEMBER 1996 By James O. Freedman