Ms. Viola Pueggel of Iowa, 71-year-old passenger on the Peter Pan tour bus whose door has just opened to the Dartmouth Green from College Street, ambles onto the edge of the grass, profess orially, her hands coupled behind her back, her red wind-breaker looking hot for the day. She wears bruised athletic sneakers, once white. A retired grade-school teacher, Ms. Pueggel notices that two parallel lines (walking paths) extend across the Green, bisected by three other lines, forming scalene triangles, rhomboids, and trapezoids. On each of these floating green wedges there is physicality going on, which as a former 4-H advisor (hands, head, heart, health) she observes approvingly.

A red Frisbee flies overhead. A football spirals against the backdrop of trees. Two volleyballs are finger-tapped back and forth, California-ishly, countervailed by a hard pepper of a lacrosse ball slung into a net, New England style. Soccer balls are smote by foot. Runners, skaters, cyclists, hikers, joggers, ski-skaters—in shorts, and not fancy ones, either—zip the grid of the Green like energy packets on a printed circuit board: yes, for they are born with a unique connection of legs to brain, and at Dartmouth the connection gets particularly improved. A man, standing erect, juggles three gold Indian cubes that sail into the air like the hominid's weapon in the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Let us start there in our observations of physicality and the student body.

Four million years ago, australopithecines—our evolutionary ancestors—walked with an upright gait. Bipedalism came about when brain sizes were about what apes' are today, meaning we got smarter as we stood and walked on two legs. The end result is the action Ms. Pueggel is observing on the Green, which, enlivened by the sun, recalls the Miocene-age African savanna where smart little hominids were racing toward humanness. One is hard-pressed to think of another college where the link between moving feet and growing minds has been so intentionally cultivated for so long.

"Dartmouth students aren't like those skinny cigarettesmokers down there at Yale," a wool-shirted alumnus tells me over orange juice and oatmeal. He isn't willing to change the workshirt-in-the-woods tradition of the College, that unique Dartmouth garment of mountains stitched by water that is not found in the agorae of New Haven or Cambridge. "Dartmouth is the Ivy League school synonymous with activity and athletics," says Jen Pariseau '97, echoing a generations-old sentiment. The sweat of a voluntary pre-season basketball practice bubbles on her forehead. "I see athletics as an integral part of education. Dartmouth attracts people who aren't content with just sitting—they want to experience what's going on around them."

The rural New Hampshire setting has spawned an ethic of work hard, play hard. People who come to Dartmouth are, historically, high achievers, motivated to excel in academics and outside academics. Says Tyler Stableford '95, "They're aware of their minds and their bodies. Our campus isn't an urban campus where you have a good likelihood of being hit by a car before you graduate." It is especially unlikely Stableford will be hit. Three hours after talking with me, he is 50 feet high on the sheer side of Gerry Hall, affixed there by the suck of his rock-climbing shoes and bite of his fingers, his legs and arms changing into impossible angles. He looks like a series of runes headed up the granite and into the clouds.

There is an older, more exclusive version of work hard, play hard: the notion of muscular Christianity, which originated in England and influenced American schools. Muscular Christianity is what Emerson described when he visited England in 1848 and wrote, "It is contended by those who have been bred at Eaton, Harrow, Rugby, and Westminster, that the public sentiment within each of those schools is high-toned and manly; that, in their play-grounds, courage is universally admired, meanness despised, manly feelings and generous conduct are encouraged.... With a hardier habit and resolute gymnastics, with five miles more walking, or five ounces less eating, or with a saddle and a gallop of twenty miles a day, with skating and rowingmatches, the American would arrive at as robust exegesis and cheery and hilarious tone [as the English]."

Today muscular Christianity resides on campus like the Rollins Chapel does: We know it is part of Dartmouth's tradition, but attendance is optional. The ablutions of sweat are now self-determined. Take physical education. In the 1920s PE at Dartmouth consisted of "Prussian-type calisthenics," says Kenyon Jones, associate director of athletics for physical education and recreation sports. Reflecting students' desires since then, PE has changed from emphasizing team sports (up through the sixties) to skills that can be carried on into later life (which is why racquetball was taught in the 70s and 'Bos, for example) to the present, when students demand courses emphasizing personal fitness and health—women learn weight lifting, men try dance aerobics.

Given the myriad of opportunities, the many facilities, and the beckoning woods, Dartmouth students invariably find some physical endeavor that suits them. Almost everyone, it seems, would rather play than watch. This, says Kenji Sugahara '95, "is the image of Dartmouth." He talks to me at the Kresge Fitness Center while he and Dan Greene '95 do military presses with barbells. They lift the bars over their heads, then lower them behind their necks, then lift again. They are pumping iron in front of a mirror, nicely repeating the image of Dartmouth muscle—stereoscopically so, because behind them in the mirror is Corrie Lyle '97, hammering her deltoids to get stronger for crew season.

A bout4,000 undergraduates attend Dartmouth. What is one to make of the 1,000 who compete in the 400 annual intercollegiate contests? Of the 300 involved in the 16 club sports ?Of the 3,000 who play in the 2,000 annual intramural events? Of the 1,500 who each day use the Alumni Gym/Berry Center complex? Of the Outing Club? The skiing programs? The outdoor education programs? Today on campus there is a reunion of Appalachian Trail walkers. I saw them near the Green playing Whiffle Ball in hiking boots.

I'm considering this while I sit in the home plate bleachers at Red Rolfe Field. I'm watching batting practice. To my right the east stands of Memorial Field rise up in a flying wedge. Farther out, the curve of the Leverone Field House roof comes rolling like a black wave about to engulf right field. Even the buildings seems to be on the move. With sounds: baseballs ping on aluminum bats; tennis balls pong on the courts next door. I decide to walk down South Park Street. This puts me behind the left field fence. There's a waif of a baseball sitting against the curb.

"Hey left fielder!" I yell, holding up the ball. "Okay," he says and taps his glove, indicating I should throw the ball over the fence to him. He rocks slightly on his toes. "Okay," I say, and I toss it in a high arc across the street, hoping the ball clears the fence, hoping the ball makes it to him on the fly.

He snaps it in his glove at shoe-level. "Thanks," he says, then folds his glove against his chest and trots back to his position.

All of a sudden, I'm feeling part of this place, even though I've never been here before: a participant. For the few seconds that ball was in flight, the left fielder and I were connected. I had thought about keeping it, but now I was glad it was in his glove. The moment was a souvenir worth more than any ball. This is what the games and outings must accomplish on a scale multiplied by the thousands of students who participate in them: They melt away separateness.

In every real human, Nietzsche said, is a child who wants to play. Playing is a ritual of belonging with the fuddy-duddyness of adulthood suspended—those reflexive patterns of thinking ground into us over the years, our unexamined moralmoralism and unchallenged complacency. If play at Dartmouth provides instruction, it is perhaps too simple to intellectualize. It is the feeling of common bonding that happens when people are so unmindful of who they are, they actually enjoy themselves and each other. Recess at Dartmouth, which begins about 3 p.m. when classes let out and the gym shorts come on, is a campus-wide exercise in team-building, esteem-building, valuing diversity, etc.—.all those things for which older adults need consultants, task forces, and, eventually, vice presidents.

"S weat," my big-handed great-great-uncle George once told me, "is sweeter than starch." This thought comes to me as I'm walking to the Green after seeing a women's first-year crew row on the Connecticut River. It's hard to imagine anything that would join people more closely than 15 miles of choreographing eight oars and then celebrating their success: They all jumped into the water when practice was over. Which brings to mind Larry Breckenridge '95, who chairs the cabin and trail division of the Outing Club. He tells me the annual 50-mile hike to Moosi lauke Ravine Lodge also has its typical Dartmouth merits: "It's good camaraderie and sufficiently abuses our bodies."

Suddenly up West Wheelock Street labor six cyclists on mountain bikes. They spin together tight. Derailleurs click as the riders shift to attack the hill. They had come over the river and this is the steepest climb. I hear them huffing and they hurt— and then a woman stands up from the saddle and yells, "Screw the hill!" She sprints ahead of the pack. Three others stand and charge after her, gleeful and young, and they work up the hill past West Street, where a sign in the window of a house says: IT'S HARD TO FIND CARDS WITH LARGE PRINT FOR PEOPLE YOUR AGE TO READ.

I walk back to the Green. It is late afternoon. They are loading the old people onto the buses. I do not see Ms. Pueggel, but I see her bus. There are the oval faces of old women in the windows. The bus is headed to the White Mountains. In a few hours some of the passengers will be dozing, while the wakeful will pass the smooth rocks of the Swift River and the heavy leaves of Mount Pass acon away, the scene passing like a movie through the square windows, nothing scented, nothing wet-feeling: watching. I hoped Ms. Pueggel had once gathered green walnuts in the woods. I hoped she had kept them with her over the years in preparation for the bus.

I have reported Dartmouth physicality from the perspective of a single, healthy day. Perhaps it is wiser to view it from a lifetime to appreciate how grit and roughness in the melt of spring—o how muddy we were that day, the two of us in love!—work against the desiccation of age. Though the loss of muscle is inevitable, though the years return us to the stoop of our most distant ancestors, what remains as strong as ever is our connection to the people and the places where we stood and felt our humanness. So much depends on the left fielder's glove.

The adult world needs task forces to create what Dartmouth students have built with sports: a sense of community.

One is hard-pressed to think of another college where the link between moving feet and growing minds has been so intentionally cultivated for so long.

Writer JOHN MONAHAN lives in Ft. Collins, Colorado.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryCan Science Save the Arctic?

March 1996 By Lynn Noel '81 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Productivity

March 1996 By James Wright -

Feature

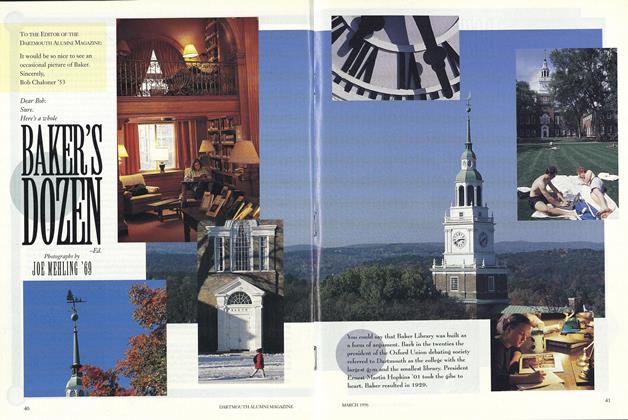

FeatureBAKER'S DOZEN

March 1996 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

March 1996 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleSpace Politics

March 1996 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

March 1996 By Armanda Iorio

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Second Look at the Russians

January 1958 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCOMMENCEMENT

June • 1985 -

Feature

FeatureROBERTA STEWART

Nov - Dec -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPoetry From the Heart

MARCH 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

FeatureFor Want of a Better Word They Called It a Strike

JUNE 1970 By DAVID MASSELLI '70 and WINTHROP ROCKWELL '70 -

Feature

FeatureRev. Frisbie's Wonderful Discovery

MAY 1978 By James L. Farley