Something changed during the last 25 years in the small lakes of Vermont's Champlain valley, and Dartmouth research biologist Richard Stemberger wants to know why. He is studying the microscopic zooplankton that have lived in the area's fresh water since the last Ice Age ended 10,000 years ago. By the time Stemberger sampled the 1990s, at least two species of zooplankton had vanished since they were last recorded in 1969.

According to Stemberger, not only are these algaemunchers the base of the food chain that leads right up to fish-eating humans; the disappearance of even a couple of species indicates "we're on a long-term slide in lake health." He is part of an eight-state EPA-funded research team that is sampling more than 11,000 lakes in the Northeast to provide both a survey of variances in lake biology and a benchmark against which future comparisons can be made.

So far the data suggest that humans are altering the biology of lakes more than many of us realize. "What we're doing to lakes by development overshadows changes from acidity," he says.

"We're urbanizing our lakes in the Northeast." Even remote lakes are at risk, he argues, since they are part of the broader, biologically linked watersheds. "We're homogenizing diversity in our lakes," he says. And that means that the clock is ticking for collecting data on natural systems and for making decisions about how to manage lakes. "Thirty years down the road, when lakes aren't as healthy, who will know the difference? People will have forgotten what was oris natural," he says. "Ifwe want a totally artificial human landscape, then that's whatwe'11 have. But maybe for posterity we ought to preserve vestiges of natural systems."

"What we're doing to lakes bydevelopment overshadows changes fromacidity," biologist Stemberger says.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

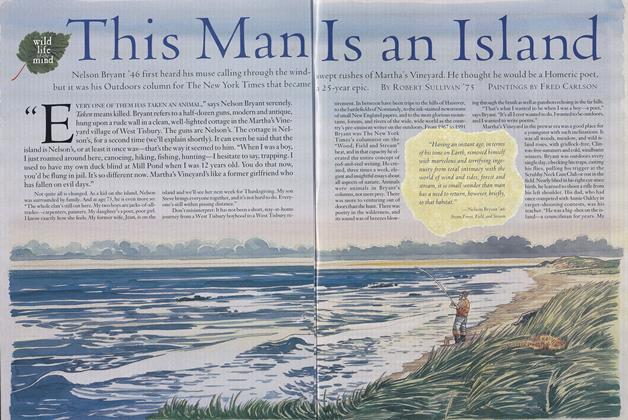

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

October 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureNaming the Animals

October 1996 By Robert Pack '51 -

Feature

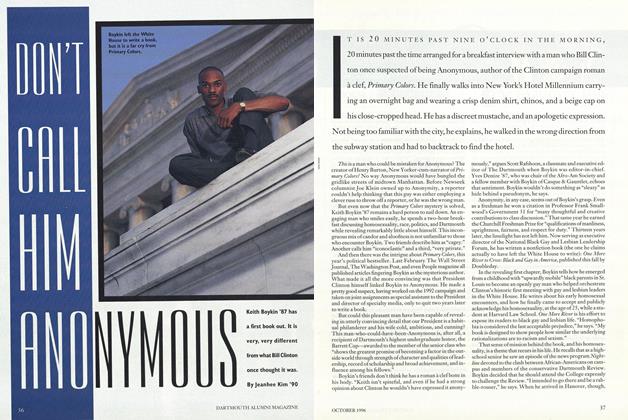

FeatureDON'T CALL HIM ANONYMOUS

October 1996 By Jeanhee Kim '9O -

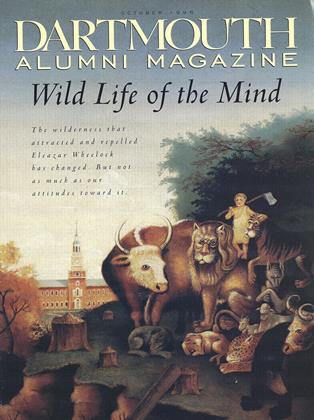

Cover Story

Cover StorySecond Nature

October 1996 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

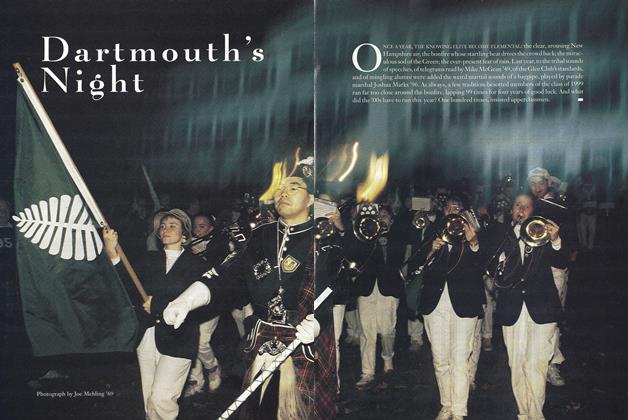

FeatureDartmouth's Night

October 1996 -

Article

ArticleKnowing Your Place

October 1996 By Jim Collins'84