Life without isn't fully human.

In Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book, Mowgli a young boy growing up in the Indian forest without human contact learns to talk with the animals. Similar tales abound in legend and myth (there's Romulus and Remus and Tarzan, for example), but such conversations aren't just the province of fiction. Linguists have long wondered what "wild children" and other linguistic anomalies may have to reveal about the nature and development of human language.

It's hard to imagine a more extreme form of developmental deprivation than for a child to be isolated from language. In a freshman seminar on "Wild Children, Klingons, and Apes: Understanding Language through Atypical Speech," assistant professor of classics and linguistics Lindsay Whaley asks students to contemplate such isolation. Whaley, whose own language expertise includes ancient Greek, Rwanda's Kinyarwanda language, and the Tungus languages of northern China, Mongolia, and Siberia, says wild children represent "the forbidden experiment, individuals who can tell us what's 'purely natural.' A wild child is both a patient and an experiment. Such cases were a way to get the class to think about learning, neuroanatomy, ethics, and other great issues for discussion."

Real-life wild children are mercifully rare. Perhaps the most famous was Victory 12-year-old boy who in 1799 walked out of the woods in Aveyron, southern France, and was treated by Dr. Jean-Marc Gaspard Itard. Frangois Truffaut's 1969 film, 'Enfant Sauvage or Wild Child, extrapolates from Dr. Itard's memoirs, showing Itard attempting to instruct Victor in elementary language. Victor learns with difficulty to match certain objects to their appropriate words and shapes as drawn on a blackboard. In the 19705, an 11 -year-old Los Angeles girl was discovered strait jacketed and chained to a crib in a locked room, where she had spent her entire life. Her father and mother had fed her but never talked to her. In the spirit of Dr. Itard, the staff of Los Angeles Children's Hospital cared for the child, whom they called Genie.

Both Genie and Victor eventually learned simple language skills, but their development was severely limited. Victor apparently learned to name objects but could not construct simple sentences. Genie mastered the construction of simple declarative sentences, but she had much greater difficulty forming questions and using such words as "why," "where," and "when." These and other experiences, says Whaley, convinced researchers that wild children do not represent a linguistic "blank slate." Linguists now hypothesize that there are critical ages by which children must learn certain elements of languagesuch as sounds and basic aspects of grammar if they are to maximize their innate language capacity. "Much of it is there at birth, but it has to be bombarded with necessary experience in order to develop fully. If not, language capacity atrophies like leg muscles in a cast," says Whaley. "Early on, it was believed there was one critical point for language, but it's now much more complex. By adolescence, however, all critical ages have passed."

On a different linguistic front, researchers in the late 1970s began experimenting with teaching wild animals to communicate. They gave elementary instruction in American Sign Language to humankind's closest relatives, chimpanzees. When Washoe, the first of the so-called "talking apes," managed to assemble a small vocabulary of signs, he became something of a scientific celebrity. The ape's apparent success at learning a language led some scientists to conclude that the capacity for language, spoken or otherwise, is not necessarily unique to the human species. Whaley disagrees. "What the chimpanzees are doing is little better than running through a maze for cheese."

The professor says his dismissal of Washoe's supposed accomplishments "caught the students by surprise." But dispelling myths about language, he says, is essential to the purpose of the course. "One of the biggest misconceptions is that language is only a kind of communication. Human beings do not base their language learning only on utility, probably not even primarily on utility. People love to make puns and use metaphor. Language is far more than just a tool."

As a method for his class to discover how authentic language goes beyond the merely pragmatic to express the extensive spectrum of emotions and human creativity, Whaley explores cases of synthetic languages. Star Trek scriptwriters, for example, invented the language "Klingon" for the series' fierce race of space warriors. Harsh and guttural, Klingon lacks words expressing forgiveness and sorrow; the aliens had no use for such notions. In real human experience, Whaley observes, the correspondence between language and culture is never quite as neat. "Vocabulary doesn't necessarily reflect the thought processes of the culture. In Dakota, a Sioux language, for example, there is no word for 'sorry,' but it's a mistake to say the Dakota people lack that emotion. They have another way to express the same idea, just not quite so directly."

The most extensive synthetic languages may well be Esperanto, which was devised in 1887 by "Doktoro Esperanto," the Polish physician Lejzer Ludwik Zamenhof. The well-meaning doctor hoped to cure the plague of misunderstanding he saw bedeviling his native continent, a plague that he blamed, in part, on confusion caused by language. He based his "universal" language on root-words common to the chief European languages.

When Whaley's students try to translate English into Esperanto, they quickly discover its limitations. In an attempt to minimize confusion, Esperanto stresses only what is necessary to communicate and' entirely lacks other more irregular elements such as idioms and a concern for aesthetics. "With poems and songs particularly, the students found some things they couldn't translate very easily. They ended up translating word for word," says Whaley. "That's where Zamenhof s vision doesn't work. It assumes that given a static set of words and rules, you have a language, but that's just not true." Deliberately concocted languages like Esperanto are the opposite of pidgin tongues, which evolve organically and dynamically as they are spoken. "Language is very messy and imprecise," says Whaley. "There's too much opportunity to misunderstand too many homonyms, too many synonyms. Social customs, class, and personality also put pressure on a language to do much more than any synthetic system would allow you."

But without the mess, it seems, we'd be completely tongue-tied.

Christ Opher Kenneally is author of The Massachusetts Legacy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StorySanta: The Dartmouth Connection

December 1996 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Novel in You, and How to Get It Out

December 1996 By Elisa Murray '88 -

Feature

FeatureSHUE HAPPENS

December 1996 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

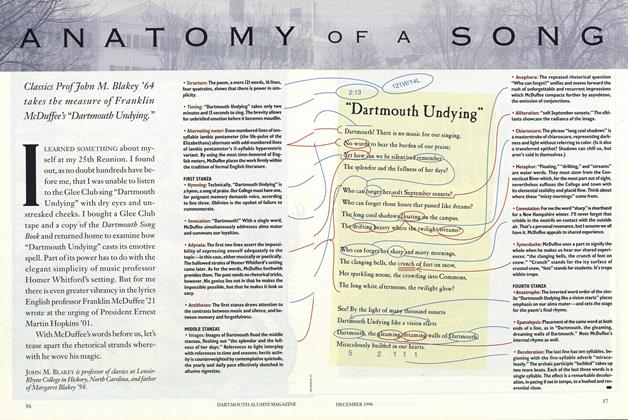

FeatureANATOMY OF A SONG

December 1996 By John M. Blakey '64 -

Article

ArticleA Quiet Greatness

December 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThose Who Got It Out

December 1996