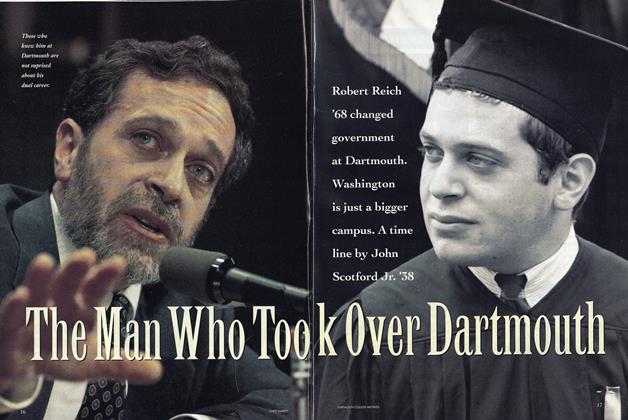

Santa: The Dartmouth Connection

The author of the book that Publishers Weekly calls “a new Christmas classic” reveals how Greeners aid and abet the annual Christmas Mission.

DECEMBER 1996 Robert Sullivan '75The author of the book that Publishers Weekly calls “a new Christmas classic” reveals how Greeners aid and abet the annual Christmas Mission.

DECEMBER 1996 Robert Sullivan '75In conducting researches during the past several years into the

science of reindeer flight and the famous Christmas Mission that is annually

mounted by an elfin community based at the North Pole, I

found myself turning again and again to Dartmouth. It should not be

surprising, perhaps, that our northland college would have strong ties

to any and all sophisticated Arctic operations. But the number and

nature of these ties were unusual indeed. It turns out that Dartmouth is far, far

more complicitous in the "Santa Claus" venture than, say, Harvard, MIT,

even NASA—admirable institutions all, but ones, apparently, with an insufficient

feel for cold-weather venturing. Or at least I now must assume. For after

wrapping up inquiries and packing them into a book, Flight of the Reindeer:

The True Story of Santa Claus and His Christmas Mission, I, a son of Dartmouth,

looked at the whole big thing and came to a surprising but altogether pleasant

conclusion: The tracks of Santa's sleigh, so elusive elsewhere in the wide wide

world, can be found everywhere in the Upper Valley.

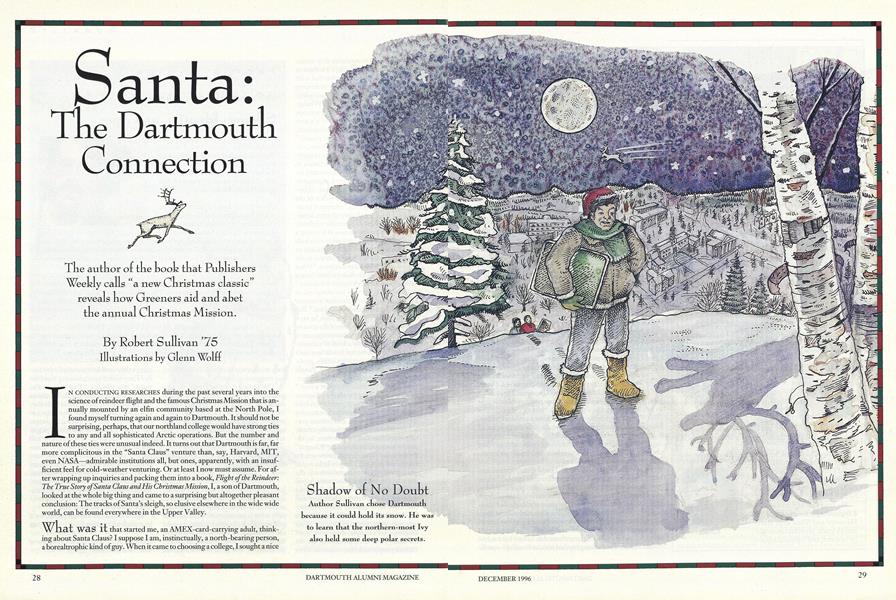

What was it that started me, an AMEX-card-carrying adult, thinking about Santa Claus? I suppose I am, instinctually, a north-bearing person, a borealtrophic kind of guy. When it came to choosing a college, I sought a nice cold one. The sole reason I didn't end up a Bowdoin Polar Bear—colors white-on-white, most famous alum Robert E. Peary—was that the salt air of the Atlantic tends to melt the snow in Brunswick, Maine. Hanover: That looked like a place that could hold its snow.

Upon graduating, I eagerly accepted any writing assignment that would push me near to or beyond the Arctic Circle. In 1984, while researching an article on the reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), I made my way to a small Inuit village in far northern Canada called Kuujjuaq. That is where I first saw a reindeer fly a mammoth 600-pound buck that stopped, turned, took a short run and, after a soft grunt and a forceful liftoff, soared 200 yards across a wide river. The Inuit with me at the time said this was nothing compared with what "the little ones" could do.

"The little ones that live farther north," one man said. "Those are the real fliers." And so I left Kuujjuaq determined to investigate reindeer farther, yes. And also: to unravel a far greater mystery.

Over time, through books and travel, contacts and interviews, I have found some clues, followed some important leads. It turns out there is a small network of people around the world who help the elf, and I have been fortunate in gaining their confidence. Among these Helpers is, pre-eminently, Oran Young, the director of Dartmouth's Institute of Arctic Studies. "The Helpers it's not an organization, it's not a fraternity, it's not a club," he told me. "It is a loosely organized network of specialists around the globe who do what they can to make things easier for him. Even we Helpers don't know who all the other Helpers are. No one does, except him—Santa. He likes lists, as you know, and I'm sure he's got a very detailed list of all his Helpers in his computer at the Pole."

Young's role is flight coordinator. His Institute has long been involved with the airlines in helping regulate traffic flow over the North Pole. "The increase in circumpolar flights has been exponential since 1970," Young said. "The world has become a much smaller place with faster and faster planes, and now it's a short hop from London to Hong Kong—over the top.

"So what I do is, I talk to the major airlines. I negotiate a one- night moratorium of their great circumpolar routes. Everyone cooperates, and I think everyone's happy to. They understand the problem. I mean, Santa's banging in and out of the Pole all night long, and if these big birds are zipping around at 30,000 feet, there's eventually going to be a problem, a terrible accident. So everyone clears the air over the Pole for 31 hours. And this is not just a U.S. thing. Aeroflot cooperates and China Air cooperates, Qantas cooperates and Air France cooperates. This annual moratorium stands, really, as a testament to the kind of man Santa is."

I must have appeared skeptical. I know that, in the modern world, money alone is what talks, and I simply couldn't believe that the airlines, what with their paper-thin profit margins, would agree to cut a single flight, let alone a score of them. And so Young wrote on a scrap of paper the name and number of another Helper. I looked. I was amazed: George Bush.

"It's just as Oran says," the former President of the United States replied when I called him at his office in Houston. "I didn't know one blessed thing about this before I got to the White House. Then during my first term as President probably about October of 1989 I was presented with this agreement that the President is asked to sign each fall. This was the international accord that directs our airlines to watch themselves, and to clear that airspace up there, up there over the Pole. I looked at the thing and I said, 'For Santa Claus? Sure.' I signed immediately. He's a great ambassador for peace and fellowship in this world. America absolutely should be in the business of encouraging his work."

I returned, chastened, to Oran Young. "You're in for more shocks, if you continue with this," he said.

"I'm continuing."

"Then traipse across the Green and seek out Phil Cronenwett in Baker. Tell him Oran sent you. Tell him I said it's okay."

if you look at the evidence—and I mean evidence, not legend then you arrive at a few pieces of certain knowledge," said Philip N. Cronenwett. "Piece Number One: Santa Claus opened shop two millennia ago, give or take a decade. Piece Number Two: He has been in business every year since, although some years, it is clear, were difficult for him very hard indeed for him to deliver during those years. Piece Number Three: He has modified his approach, he has gotten better at what he does. Piece Number Four, and this is a tangent to Piece Number Three: He has had to change his location. He did not start all this at the North Pole. That's something I find fascinating."

Who was who is this Philip N. Cronenwett, and how did he know these things with such certainty?

He is the Special Collections librarian at Baker, which has, perhaps, the best collection of Arctic artifacts and literature in the country. Cronenwett is keeper of the library's most valuable books. He has read them, all of them. He has put together the pieces.

"Santa Claus is two things indisputably: He is an elf, and he is a good man," said Cronenwett as he leaned back in his chair. "I have never been able to learn where he was born, but Ido know that his...his 'village,' if you want to use the term, was originally situated in southcentral Greenland." Cronenwett cited chapter and verse from great antiquated volumes. "We have writings from eleventh-century Iceland," he said, not a little proudly. "We have books of cave art from eleventh-century Canada or, rather, the region we now call Canada."

He sketched a chronology of dramatic events. Avast community of elves, led by the one who would come to be known as Saint Nicholas or, more commonly, Santa Claus, was established in Greenland untold centuries ago. It was quite near what is now a small Sami camp known as Holsteinborg, and the citizens of Holsteinborg have found many relics from Claus's first setdement. From the earliestyears A.D. until the turn of the first millennium, the centerpiece of Santa's society was its annual Mission, a fantastic one-night global voyage the intent of which was, from the first, to bring cheer to the world's least fortunate.

But Holsteinborg, as it turned out, provided only temporary quarters. In the tenth century, human beings started to drift onto Greenland from Iceland, Labrador, and elsewhere. (Whether their presence was of any concern to Claus's elf community is unclear, but it seems Santa Claus has always been less wary of northernfolk than of Europeans, for whatever reasons.)

Then in the spring of 986, 25 Viking ships led by Eric the Red sailed across the Greenland Sea laden with fowl, farm animals, and 750 Icelanders. The passage was treacherous, and only 15 ships survived. But a foothold had been gained, and in the next few years thousands of Icelanders joined their Norse kinfolk in the Osterbygd, or "eastern setdement." Word of the migration seeped inland, and Santa Claus decided that his own small nation had to be moved. Elves can live 5,000 years, but only if they are left unharmed, Cronenwett explained to me. They are so small and so docile by nature that they present no match for humans. Claus acted quickly and forcefully when he learned of a growing European presence on the island.

Cronenwett moved from his office into Baker's dark, oiledwood Treasure Room, where, from a glass case, he took two mammoth volumes bound in leather Journals of the Osterbygd. "Look here," he said as he leafed through the ancient pages. "You can't read the words because they're in Old Icelandic, but in translation this page recounts, 'Activity to the west...Eskimo? Elves?.. .Night movement sighted by scouting parties...' And over here..." He turned several more pages. "This says, in translation, that the Vikings found an intact, absolutely abandoned city of five miles square, a city that would have housed people less than half the Vikings' own size. You see? What this means is, Eric's men found Santa's first village! But they were too late. The whole Claus nation was able to beat it out of there before the Vikings swooped down. It's one of the great reconnaissances in history."

The elves had moved south-southwest across the Atlantic, by dogsled, boat, and sleds pulled by the flying reindeer. They set up an elfin city in what is now called Goose Bay, in Labrador, Canada. And there they lived until the year 1000, when Eric's son Leif became the first Viking to view the mainland of North America. And to be viewed in turn. From the harbor where his commune was taking root, Santa Claus saw Ericsson's ships. He knew what he had to do.

"Leaving Labrador for the Arctic was the only option available," said Cronenwett. "He must have known the onlyplace in the whole world where he would be left alone was on the polar ice cap. He knew that his elves were the only beings on the planet who could survive where there was no place to grow food no ground, no soil, nothing. How? The flying deer would allow them to establish an operation that imported food! My guess is that Santa knew that whatever provisions they needed in those difficult early years could be scavenged at night throughout Europe, Asia, and North America by reindeer-riding elves, who would then fly back to the Pole. In a way, they were the original homeless people of the northern world. Until they got the village up and running, they basically lived on scraps."

The exodus of elves to the North Pole was a difficult one, over the windswept hills of Baffin and Ellesmere islands, and finally to the Arctic cap. There, in the late spring of 1001, the elves saw the great ice of the far northern Adantic start to break up behind them, giving way to open, frigid, impassable water. Fatal water. They looked back from their new, eternally floating homeland on the ice and knew that they had severed ties forever with all earthly continents.

Except...They hadn't. For decades they came each night for food. And, of course, once a year every year, they or at least he returned to cany out the extraordinary Mission that was theirs and theirs alone.

It hasn't been easy. In the twentieth century, things are dicier than they were when the opposition was merely a bunch of oarpulling Vikings. These days, humans, not just elves, can take to the air. Technology makes the Arctic an accessible, even livable place. What has kept man from absorbing the village into the world community? What has preserved Claus's relative anonymity, his privacy, his mystery? What has protected him, and allowed him to keep on keeping on?

"There's absolutely no way Santa Claus and the entire village could be so seldom seen if they were anywhere else on the globe," Oran Young told me. "Every other location is fixed in space and time, but I've studied the North Pole, and I can tell you—it's a very mysterious place. There's often fog, and there are these mountains of ice all around. Plus, the way the ice floats swirling and sailing like it does—well, the huge ice ridge that you saw in the west yesterday can be in the north tomorrow, and it can be east the day after that. You start to thinkyour compass is going crazy. It makes Santa's village nearly impossible to locate. It's the only town in the entire world that does not lie at a specific latitude and longitude. It moves."

It moves, yes, but fast enough? Not always. Mankind, over time, did come to know this elf called Santa Claus to know him well, to know him personally, even if sightings of him remained few indeed. Here are a few of the things I was able to track down about the jolly elf: It turns out Claus makes 1,700-plus Christmas Eve round trips from the Pole annually, picking up cargo each time. He must travel nearly 75 million miles each December 24-25 to serve all the world. Even at his phenomenal rate of speed we'll get to that, momentarily Claus needs all the darkness that the night of December 24-25 can afford. Thanks to the rotation of the earth, and the fact that the more populous Northern Hemisphere is in its season of longest nights, he has not 24 but a fall 31 hours to work with. "He uses all of it," said Oran Young. "Every second. In fact, at the westernmost edge of the dateline, those islands in the Pacific are loaded with reports of someone or something banging around at dawn, creating a ruckus. He's not a vampire, after all, and there are lots and lots of people who swear they've seen him in daylight."

Young was intrigued by what speed Santa's laden sleigh might be achieving each year, and so—purely as a lark—he devised an experiment in 1991 to find out. The experiment, for which he enlisted the assistance of College Photographer Joe Mehling '69, ultimately confirmed the viability of Claus's annual one-night global voyage. "When he approached me, I thought Oran was nuts," Mehling told me. "But as you can see, it worked. Amazing." (For a glimpse of the Mehling-Young Speed Test, see page 32.)

Even at suck a speedy rate as 650 miles per second, Claus cannot cover the globe strictly adhering to round-trips. His deer need sustenance, and though they receive some during their 1,756 polar pit stops, it isn't enough. And so, each November for nearly 2,000 years, reconnaissance missions fleet of elves on reindeerback have flown the farflung skies, readying the world to receive its gift-giver. Their cargo is mostly slow-burning, high-fat foods. It includes exotica like muktuk from North Adantic whales and jerky from Lapland elk, as well as the reindeer staples: cracked barley, fish-meal, cottonwood sawdust for fiber, molasses for fast-twitch energy, salt. The elves secure these things in woodsummits of mountains. These peaks are the prominent ones, instantly recognizable from on high. Any pilot can pick these singular mountains out of a dense range, and Santa Claus is not just any pilot.

"I asked Santa about the Everest rumors," said Will Steger, the famous Arctic explorer who has twice reached the Pole overland, and who actually stumbled upon the village during his 1986 expedition. "He smiled and said, 'Yes, sure. That was the first stop I ever used. I've been using it for years.'"

There had been stories and legends about this for decades: That something strange was going on at die top of die world's highest mountain. Tibetans and Nepalese who live in the shadow of the great peak had long felt that someone or something was at work up there, particularly in late autumn and early winter. In fact, for four decades rumors had circulated in the mountaineering community that the most famous climbers in history actually found evidence of a Claus cache on Everest. Even now, all these years after his monumental achievement, Sir Edmund Hillary would not confirm the stories. But he would not quite deny them, either.

Speaking from his home in Auckland, New Zealand, Sir Edmund, who is today 77 years old and still in fine fettle, talked guardedly but warmly about those dramatic days in 1953 when he and his Sherpa climbing companion, Tenzing Norgay—who died in India in 1987 at the age of 72 thrilled the world by becoming the first men to successfully climb Everest. Adding new information to the Everest story for the first time in 40 years, Sir Edmund addresses the Santa Claus questions squarely, while emphasizing that evidence has always remained elusive.

"The Buddhist monks in the Tengboche Monastery at the foot of Mount Everest gave us our blessing for the success of our climb," said Sir Edmund. "The Head Lama pointed out his belief that some of their gods often spent a little time on the summit of the mountain, and asked us not to disturb them."

Sir Edmund paused, then recalled for me the climactic day. " Six weeks later, Sherpa Tenzing and I labored up the last steep slopes and emerged on the summit of the mountain. What an exciting moment that was!

"I looked carefully around no signs of humans and no signs of gods. But T enzing was placing some small cookies and some chocolate in a small hole in the snow. Was it food for his gods or maybe even Santa himself? "I never did ask him that question!"

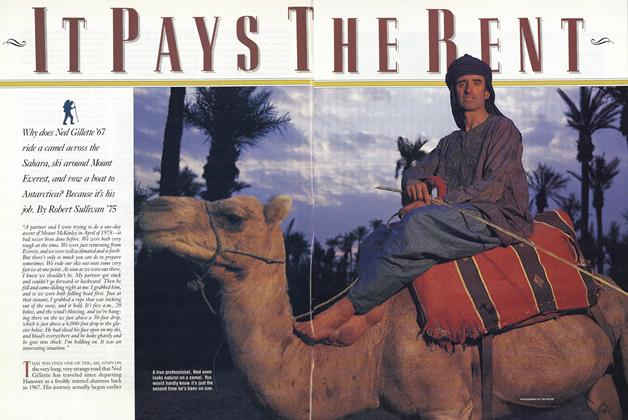

There's a postscript to Hillary's reminiscence, and it involves yet another Son of Dartmouth: Ned Gillette '67, a former Olympic cross-country skier and inveterate adventurer. He now lives in Sun Valley, Idaho, and reached Everest's 29,028-foot summit himself in 1992. I was talking to Gillette one day for a Sports Illustrated profile, and our discussions wound, eventually, 'round to this Santa Claus passion of mine. (I'm insufferable that way.) To my astonishment, Gillette told me that he had found what Hillary and Tenzing must have missed by inches. He smiled a Cheshire Cat smile, and I thought he was putting me on. He swore it was a fact; he told me he would send me a photo, and he subsequently did.

"I literally stumbled onto the box," said Gillette. "I was the last one on our team as we made our way over the Hillary Step at 28,800 feet and up towards the top. The guy in front of me on the rope kicked some snow away, and there it was. I didn't know what it was, though of course I'd heard the rumors about Hillary and Norgay and Santa. I thought, 'Maybe this is the food storage. Maybe it's true!'

"I looked around, and I'll tell you something interesting. Just below the Step, just southeast of the summit, there's a little hollow a halfmoon crescent of flat rock tucked in against the cliff. You could stand there, four or five men could stand there. It wouldn't be a bad place for a rest.

"And then I imagined it the sleigh coming through the night sky, Santa seeing the highest peak on earth, banking gently and circling down toward it. The whole great team, taking a rest as the stars in the heavens create a firestorm in the black sky. It was a lovely vision."

A lovely vision, to be sure. Avision to cherish. Avision Dartmouth is playing a great role in preserving. A role Santa Claus is grateful for, as I learned one afternoon in Ely, Minnesota. I was there interviewing Steger about that magical afternoon in 1986 when he enjoyed a tour of the elfin community, and a most remarkable audience with the great one himself.

"Santa told me," said Steger, "that he's well aware of the hard work being done on his behalf by people in and around Hanover. CRREL (the army's Hanover-based Cold Regions Lab) helps him, as you might imagine, and Oran's Institute of course. He likes the College, likes it very much. He was joking about that at one point. He said that if it had been the custom of elves to pursue secondary education, he would've chosen Dartmouth. Then he gave that chuckle of his it really is sort of 'Ho, ho, ho,' but not as basso as you'd expect he's only three feet tall, after all, and these elves, even the fat ones, don't really have deep voices.

"And then Santa added, 'But I don't think I could've got in!'"

Shadow of No Doubt author Sullivan chose Dartmouth because it could hold its snow. He was to learn that the northern-most Ivy also held some deep polar secrets.

An Explorer's

Colleagues

In Baker Library,

Arctic expert in

residence Vilhjalmur

Stefansson and his

Inuit contacts stashed

crucial evidence of

the elf en HQ.

The Speed Test Flight of the Reindeer reveals a time-lapse test by College Photographer Joe Mehling '69 and Arctic Institute head Oran Young, who clocked the sleigh at 650 miles a second.

Gillette's Evidence Adventurer Ned Gillette '67 scaled Mt. Everest ill 1992 What he found just below the summit confirmed him as a Claus believer.

Signing the Claus Clause "I looked at the thing and I said, 'For Santa Claus? Sure, " reported George Busk of an accord that bars flights over the Nortk Pole every christmas Eve.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Novel in You, and How to Get It Out

December 1996 By Elisa Murray '88 -

Feature

FeatureSHUE HAPPENS

December 1996 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

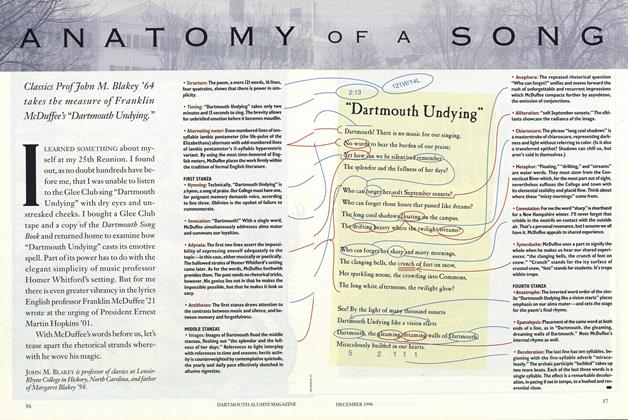

FeatureANATOMY OF A SONG

December 1996 By John M. Blakey '64 -

Article

ArticleA Quiet Greatness

December 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThose Who Got It Out

December 1996 -

Article

ArticleSpeak!

December 1996 By Christopher Kenneally '81

Robert Sullivan '75

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

APRIL 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Higher-Ed Book Biz

JUNE 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

ArticleFootball From Down Under

December 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

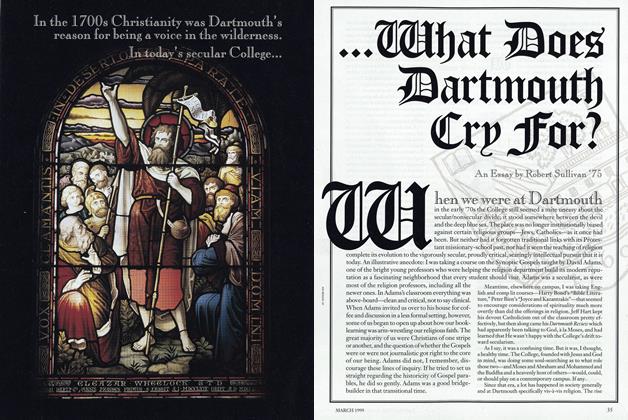

Cover StoryWhat Does Dartmouth Cry For?

MARCH 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

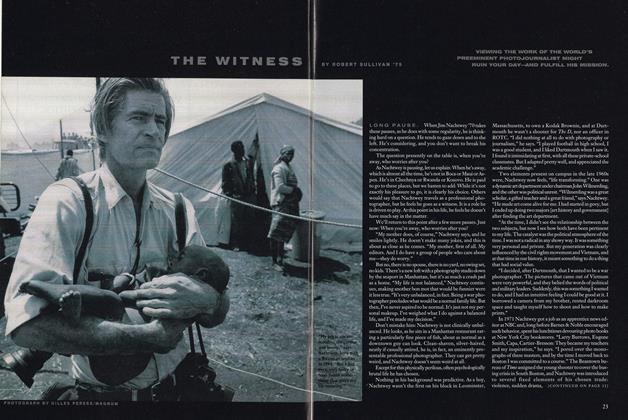

Cover StoryThe Witness

JUNE 2000 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe New New York

Jan/Feb 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75