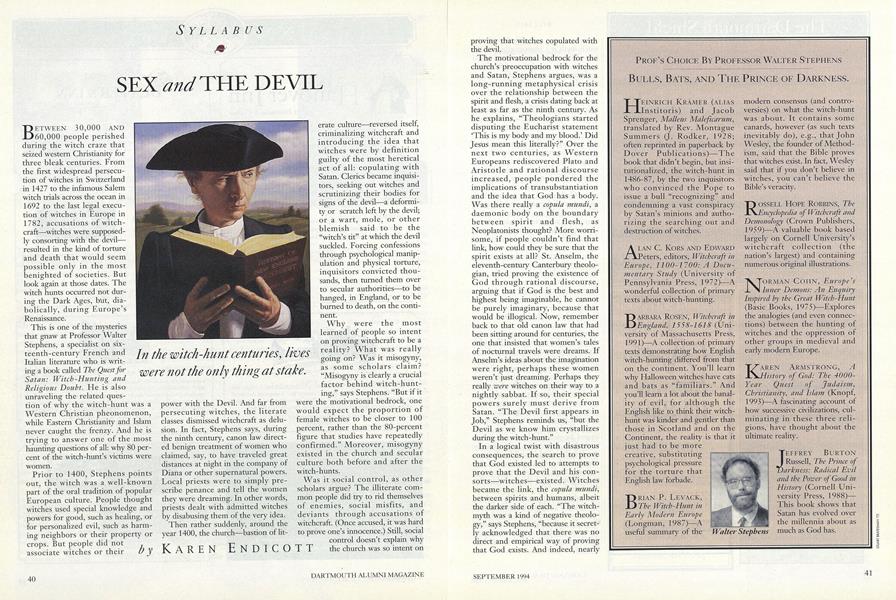

BETWEEN 30,000 AND 60,000 people perished during the witch craze that seized western Christianity for three bleak centuries. From the first widespread persecution of witches in Switzerland in 1427 to the infamous Salem witch trials across the ocean in 1692 to the last legal execution of witches in Europe in 1782, accusations of witchcraft—witches were supposedly consorting with the devil-resulted in the kind of torture and death that would seem possible only in the most benighted of societies. But look again at those dates. The witch hunts occurred not during the Dark Ages, but, diabolically, during Europe's Renaissance.

This is one of the mysteries that gnaw at Professor Walter Stephens, a specialist on sixteenth-century French and Italian literature who is writing a book called The Quest forSatan: Witch-Hunting andReligions Doubt. He is also unraveling the related question of why the witch-hunt was a Western Christian pheonomenon, while Eastern Christianity and Islam never caught the frenzy. And he is trying to answer one of the most haunting questions of all: why 80 percent of the witch-hunt's victims were women.

Prior to 1400, Stephens points out, the witch was a well-known part of the oral tradition of popular European culture. People thought witches used special knowledge and powers for good, such as healing, or for personalized evil, such as harming neighbors or their property or crops. But people did not associate witches or their power with the Devil. And far from persecuting witches, the literate classes dismissed witchcraft as delusion. In fact, Stephens says, during the ninth century, canon law directed benign treatment of women who claimed, say, to have traveled great distances at night in the company of Diana or other supernatural powers. Local priests were to simply prescribe penance and tell the women they were dreaming. In other words, priests dealt with admitted witches by disabusing them of the very idea. Then rather suddenly, around the year 1400, the church—bastion of literate culture—reversed itself, criminalizing witchcraft and introducing the idea that witches were by definition guilty of the most heretical act of all: copulating with Satan. Clerics became inquisitors, seeking out witches and scrutinizing their bodies for signs of the devil—a deformity or scratch left by the devil; or a wart, mole, or other blemish said to be the "witch's tit" at which the devil suckled. Forcing confessions through psychological manipulation and physical torture, inquisitors convicted thousands, then turned them over to secular authorities—to be hanged, in England, or to be burned to death, on the continent.

Why were the most learned of people so intent on proving witchcraft to be a reality? What was really going on? Was it misogyny, as some scholars claim? "Misogyny is clearly a crucial factor behind witch-hunting says Stephens. "But if it were the motivational bedrock, one would expect the proportion of female witches to be closer to 100 percent, rather than the 80-percent figure that studies have repeatedly confirmed." Moreover, misogyny existed in the church and secular culture both before and after the witch-hunts.

Was it social control, as other scholars argue? The illiterate common people did try to rid themselves of enemies, social misfits, and deviants through accusations of witchcraft. (Once accused, it was hard to prove one's innocence.) Still, social control doesn't explain why the church was so intent on proving that witches copulated with the devil.

The motivational bedrock for the church's preoccupation with witches and Satan, Stephens argues, was a long-running metaphysical crisis over the relationship between the spirit and flesh, a crisis dating back at least as far as the ninth century. As he explains, "Theologians started disputing the Eucharist statement 'This is my body and my blood.' Did Jesus mean this literally?" Over the next two centuries, as Western Europeans rediscovered Plato and Aristotle and rational discourse increased, people pondered the implications of transubstantiation and the idea that God has a body. Was there really a copula mundi, a daemonic body on the boundary between spirit and flesh, as Neoplatonists thought? More worrisome, if people couldn't find that link, how could they be sure that the spirit exists at all? St. Anselm, the eleventh-century Canterbury theologian, tried proving the existence of God through rational discourse, arguing that if God is the best and highest being imaginable, he cannot be purely imaginary, because that would be illogical. Now, remember back to that old canon law that had been sitting around for centuries, the one that insisted that women's tales of nocturnal travels were dreams. If Anselm's ideas about the imagination were right, perhaps these women weren't just dreaming. Perhaps they really were witches on their way to a nightly sabbat. If so, their special powers surely must derive from Satan. "The Devil first appears in Job," Stephens reminds us, "but the Devil as we know him crystallizes during the witch-hunt."

every concept associated with the witch-myth is a photographic, black-for-white negative of a theological concept. The copulation of the witch and the demon is a pathetic and degrading parody of the Incarnation of Christ, with the witch serving as anti-Mary and the Devil as Unholy Spirit. The trial of the witch is a negative of the ordeal of a martyr: one suffers to prove the omnipotence of God, the other, that of the Devil."

But why go to this negative theology? Says Stephens, "Western Christianity was enamored of rational discourse to such an extent that it long believed that nothing, not even God, was immune to dialectical proof. And when God turned out to be indeed immune to dialectical proof, Western Christianity did not fall back on mysticism and subjective modes of certainty (the paths to faith taken more decisively by Eastern Christianity and Islam). Rather it took a further step into rationalism by trying to substitute empirical proof for the missing dialectical proof. In this sense, it is no accident that the discourse of witch-hunting and the discourse of scientific inquiry in sixteenth and seventeenth-century Europe show such remarkable overlap."

And why were women so often the victims of the witch-hunt? The idea that witches copulated with the Devil explains the targetting of women, Stephens argues. Why were 20 percent of the victims male? Because accused witches were forced to confess lists of other witches. Under torture, says Stephens, you name everyone you know, male or female.

By the late sixteenth century such extorted charges were being challenged by people whose own imagined ideas about what possession by the Devil would look like did not always mesh with the actions of the accused. Such inconsistency marked the beginning of the end for the witch-hunts. "Once the consensus about the signs of witchcraft was broken, people couldn't be bullied back into consensus," says Stephens. Ungodly suffering in its wake, no closer to God than when it began, the theology of the witch-hunts had burned itself out.

In the witch-hunt centuries, liveswere not the only thing at stake.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

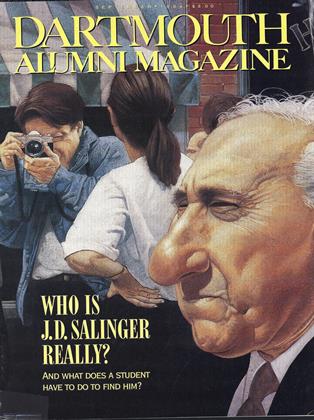

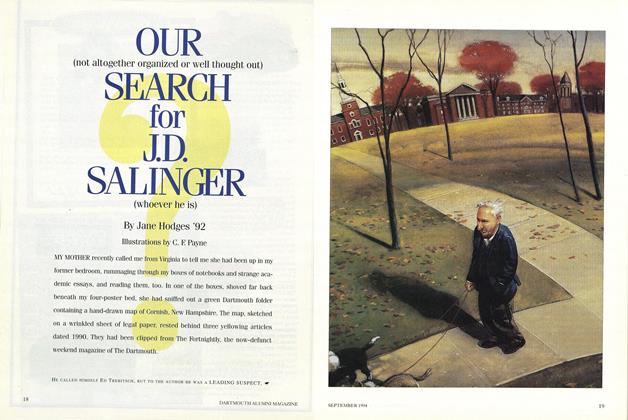

Cover StoryOUR SEARCH FOR J.D. SALINGER

September 1994 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

FeatureTales from the Info Booth

September 1994 -

Feature

FeatureThe Run

September 1994 By Stephen Madden -

Article

ArticleWhat the Soul Asks

September 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Class Notes

Class Notes1994

September 1994 By Nihad Farooq -

Class Notes

Class Notes1947

September 1994 By Ham Chase

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AUTHORS

SEPTEMBER 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AUTHORS

NOVEMBER 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Hero in American Education

NOVEMBER 1989 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleJoining the Queue

May 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleHold that Curriculum

June 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleA Cautionary Tale

April 1995 By Karen Endicott