Dartmouth requires them, however vaguely. Many, many schools do not.

Last fall Dartmouth won a bit of glory. U.S. News & World Report announced that we provided the best undergraduate teaching of any major university in the country. Such a judgment is necessarily subjective. No editor at a magazine can possibly know what the teaching is like at all major universities. He can collect data and he can do polls. In the end makes guesses.

But there are a few objective criteria, and I have been amusing myself with one of them. For good

teaching—or any teaching—to take place, a student and a professor must first encounter. This can happen in class, or on the street. It can also occur in the teacher's office. If the teacher is there.

I've been looking at office hours. And I found that our policy supports what U.S. News claims. We require the faculty to have them. Many, many places do not.

The Dartmouth requirement is sufficiently vague, God knows. It just says that teachers are expected to have some. A fair number of us interpret "some" quite modestly. But we are still ahead of, for example, the other Ivies. Keely Boivin, our administrative assistant in Environmental Studies, is much defter on the phone than I am. At my request she called them all. Here is what they told her.

Harvard has no policy. It is often possible to make an appointment with a teacher, but there are usually no stated hours when a student can just drop by.

Even appointments can be difficult. Take the experience of Peter Bien. Normally he is the Beebe Professor of the Art of Writing at Dartmouth, a man accustomed to meeting frequently with undergraduates. But recently he spent a year at Harvard as the Seferis Professor.

"What did you have for office hours?" I asked him recently.

He smiled. "Office hours? I couldn't have those. My office was in a locked section of Widener Library."

"So you never saw a student out of class?" Peter thought. "Well, I worked with two graduate students."

"How did they get to your office?" "They didn't. I met them at the locked gate."

Not all the other Ivies are as rigorous as Harvard about protecting their faculty from student intrusion. Take Columbia. Even though its representatives told Keely they have no policy, in fact they do. And many departments honor it. The English department does, for example. Result: 43 of the 44 people teaching English at Columbia last fall held office hours. Eight of them, to be sure, managed just one lonely hour a week. But 22 scheduled two hours, and 11 stretched to three. At the very top, two had four hours. One of them was David Kastan, previously of Dartmouth.

Now look at our English department. All Kastans. Every member is expected to have two office hours for each course he or she teaches, which generally means four hours in a teaching term.

Some of our departments, such as anthropology, do not have such a rule, and perhaps don't need to require accessibility. "We have strong expectations, which faculty meet," says Hoyt Alverson, the chair.

Chemistry, like an thro, has no set number of hours. But as Professor Roger Soderberg says, "In fact, most of us are around all day. Students tend to drop by without much regard to published office hours. This makes us quite a bit different from many departments outside the sciences, where faculty are likely to be on site only when teaching or during formal office hours."

And some of us do keep the formalities short. There is one member of the philosophy department who has eight office hours spread over four days; there's another who manages an hour and a half, on one day. One religion prof has a single office hour.

Furthermore, policy and practice sometimes diverge. The chair of the history department tells me they have a policy of at least three office hours a week during a teaching term. Eleven of the 16 historians who taught last fall met or exceeded that number. But not the other five. They dwindle down as low as one and a half.

There's many a fine teacher outside the sciences who is essentially around all day, and available to students. I think of Bill Spengemann and Bill Cook in English, Charlie Wood in history. There are many good teachers at Harvard, Yale, etc. Some of them have offices a student can reach, and are generally in them.

But all the same, formal office hours do make a crude indicator. Is the institution's final emphasis on supporting faculty research, or is it on educating students? I rejoice that at Dartmouth it remains, by however slender a margin, on students. a

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

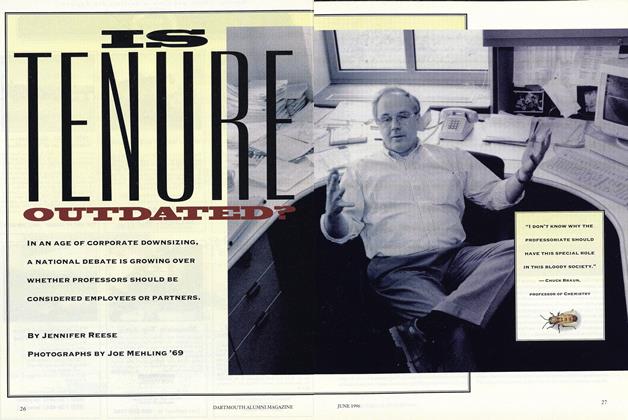

Cover StoryIS TENURE OUTDATED?

June 1996 By JENNIFER REESE -

Feature

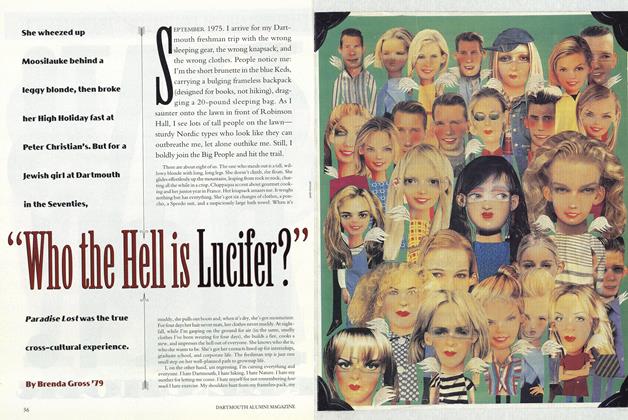

Feature“Who the Hell is Lucifer?”

June 1996 By Brenda Gross ’79 -

Feature

FeatureNoble Boots

June 1996 By Chris Clarke ’75 -

Feature

FeatureAMEN! TO THE GOSPEL CHOIR

June 1996 By Suzanne Leonard ’96 -

Article

ArticleUnderground Reading

June 1996 By Kathleen Burge ’89 -

Article

ArticleThe First Four-Minute Mile and the Last Coverup?

June 1996 By “E. Wheelock”

Noel Perrin

-

Books

BooksTHE DISPLACED PERSON'S ALMANAC.

March 1962 By NOEL PERRIN -

Article

ArticleHonor by Degrees

MAY 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleEnvironmental Impact

SEPTEMBER 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleA Lottery Where Everyone Wins

APRIL 1999 By Noel Perrin -

CURMUDGEON

CURMUDGEONSkating on Thin Ice

MARCH 2000 By Noel Perrin -

CURMUDGEON

CURMUDGEONHarness The Gym Rats

Nov/Dec 2000 By Noel Perrin