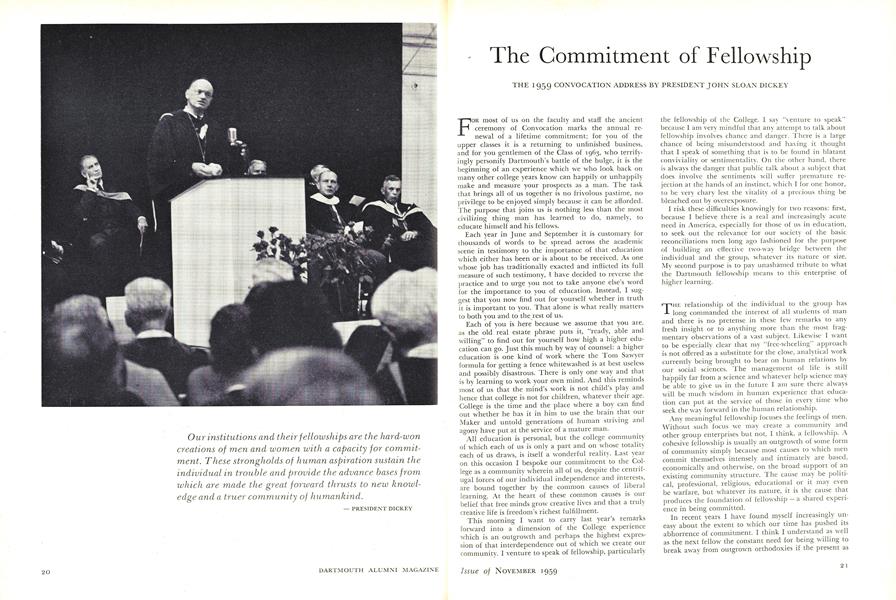

THE 1959 CONVOCATION ADDRESS BY

FOR most of us on the faculty and staff the ancient ceremony of Convocation marks the annual renewal of a lifetime commitment; for you of the upper classes it is a returning to unfinished business, and for you gentlemen of the Class of 1963, who terrifyingly personify Dartmouth's battle of the bulge, it is the beginning of an experience which we who look back on many other college years know can happily or unhappily make and measure your prospects as a man. The task that brings all of us together is no frivolous pastime, no privilege to be enjoyed simply because it can be afforded. The purpose that joins us is nothing less than the most civilizing' thing man has learned to do, namely, to educate himself and his fellows.

Each year in June and September it is customary for thousands of words to be spread across the academic scene in testimony to the importance of that education which either has been or is about to be received. As one whose job has traditionally exacted and inflicted its full measure of such testimony, I have decided to reverse the practice and to urge you not to take anyone else's word for the importance to you of education. Instead, I suggest that you now find out for yourself whether in truth it is important to you. That alone is what really matters to both you and to the rest of us.

Each of you is here because we assume that you are, as the old real estate phrase puts it, "ready, able and willing" to find out for yourself how high a higher education can go. Just this much by way of counsel: a higher education is one kind of work where the Tom Sawyer formula for getting a fence whitewashed is at best useless and possibly disastrous. There is only one way and that is by learning to work your own mind. And this reminds most of us that the mind's work is not child's play and hence that college is not for children, whatever their age. College is the time and the place where a boy can find out whether he has it in him to use the brain that our Maker and untold generations of human striving and agony have put at the service of a mature man.

All education is personal, but the college community of which each of us is only a part and on whose totality each of us draws, is itself a wonderful reality. Last year on this occasion I bespoke our commitment to the College as a community wherein all of us, despite the centrifugal forces of our individual independence and interests, are bound together by the common causes of liberal learning. At the heart of these common causes is out belief that free minds grow creative lives and that a truly creative life is freedom's richest fulfillment.

This morning I want to carry last year's remarks forward into a dimension of the College experience which is an outgrowth and perhaps the highest expression of that interdependence out of which we create our community. I venture to speak of fellowship, particularly the fellowship of the College. I say "venture to speak" because I am very mindful that any attempt to talk about fellowship involves chance and danger. There is a large chance of being misunderstood and having it thought that I speak of something that is to be found in blatant conviviality or sentimentality. On the other hand, there is always the danger that public talk about a subject that does involve the sentiments will suffer premature rejection at the hands of an instinct, which I for one honor, to be very chary lest the vitality of a precious thing be bleached out by overexposure.

I risk these difficulties knowingly for two reasons: first, because I believe there is a real and increasingly acute need in America, especially for those of us in education, to seek out the relevance for our society of the basic reconciliations men long ago fashioned for the purpose of building an effective two-way bridge between the individual and the group, whatever its nature or size. My second purpose is to pay unashamed tribute to what the Dartmouth fellowship means to this enterprise of higher learning.

THE relationship of the individual to the group has long commanded the interest of all students of man and there is no pretense in these few remarks to any fresh insight or to anything more than the most fragmentary observations of a vast subject. Likewise I want to be especially clear that my "free-wheeling" approach is not offered as a substitute for the close, analytical work currently being brought to bear on human relations by our social sciences. The management of life is still happily far from a science and whatever help science may be able to give us in the future I am sure there always will be much wisdom in human experience that education can put at the service of those in every time who seek the way forward in the human relationship.

Any meaningful fellowship focuses the feelings of men. Without such focus we may create a community and other group enterprises but not, I think, a fellowship. A cohesive fellowship is usually an outgrowth of some form of community simply because most causes to which men commit themselves intensely and intimately are based, economically and otherwise, on the broad support of an existing community structure. The cause may be political, professional, religious, educational or it may even be warfare, but whatever its nature, it is the cause that produces the foundation of fellowship - a shared experience in being committed.

In recent years I have found myself increasingly uneasy about the extent to which our time has pushed its abhorrence of commitment. I think I understand as well as the next fellow the constant need for being willing to break away from outgrown orthodoxies if the present as well as the past is to be creative. Every generation is surely entitled to know for itself the joy of pushing forward the fulfillment of man's mind. But as with every good and necessary thing the flight from unwarranted and unwise commitment has its excesses and its vagaries. I have wondered, for example, whether the fad of nihilism among the intellectuals of czarist Russia did not play a full part in depriving that society at a critical time of the only leadership that might have saved it from its demise by both suicide and murder. Whatever the ills of American society, we can say that at least up to now we have never for long lost our capacity for the kind of commitment that is necessary to a positive response in large human affairs.

THE American experience bears a strong witness that the interdependence of community and fellowship is not a form of weakness or lack of self-reliance. On the contrary, this kind of dependence is an aspect of strength; it is an addition to independence, not a diminution of it.

I am not at all sure that we can say precisely at what point any joint enterprise ripens into a fellowship, but I have a hunch that the difference between most cooperat ive ventures and a true fellowship is found somewhere between doing and thinking something together and of feeling differently about that something than you do about anything else. When you are committed that way the cause gets into your innards and becomes a part of your most indestructible belief - your belief in yourself. In such a fellowship each of us, without surrendering his individuality, becomes for that purpose, to that extent, and at that moment as one with each other in our capacity for both giving and receiving. I wonder whether at the group level this is not akin to what the eminent European Rabbi, Leo Baeck, wanted us to understand when he wrote: "The mark of a mature man is the ability to give love, and to receive it - joyously and without guilt. All the rest is commentary."

It is a maxim of sad experience that thieves stick together, and currently we hear of frightful juvenile crimes committed under the stimulus of gang fellowship. Even the vagary "beatnikism" seems to have come full circle into a sort of pathetic fellowship in its flight from commitment and conformity. All of which is simply to say that the quality of any fellowship, like a stream, never rises higher than its source - its cause.

All of us gathered together here stand in the mainstream of one of the most significant and honorable fellowships in all human experience, the fellowship of teachers and scholars, bound together by the pursuit of learning. In this ancient fellowship teachers and students have found joy and on occasion the courage of companionship to dare thoughts which, although at the time unwelcome in the larger community, later served all mankind. It was from this sense of family-like fellowship that educational institutions became alma mater to their graduates as sons and daughters of a fostering mother.

MUCH nonsense and some rather frightful songs have been perpetrated under the honored aegis of alma mater, but on balance I believe that most students of these institutions would conclude that the concept has had validity and value. At Dartmouth, although the words "alma mater" are currently not in high fashion, there are no more genuinely honored words than Hovey's "Men of Dartmouth" and we are, I think, the richer for it.

It is a commonplace in the American academic world that Dartmouth men have a unique feeling, indeed a passion, for their College. We are not correspondingly famed for our reticence on the subject, but I am sure that many of you share the weariness I feel at hearing new acquaintances in the outer world relate with the gusto of fresh discovery, the old wheeze that Dartmouth is not a college, it's a religion. However that may be, there are few people, men or women, who have had a relationship of belonging in any capacity to this College who have not prized it.

Commitment to any human cause sooner or later tests a man's capacity for loyalty. This is simply to say that anything human is perforce imperfect and from time to time has troubles and need of help. A college is exhibit "A" of this proposition and Dartmouth is no exception. The extraordinary resiliency of this College whatever her problems has often been noted by the leaders of other institutions. I suggest to you that such built-in strength is anchored in a loyalty that from generation to generation has recognized, as all true loyalty must, that the on-going College is always greater than either its triumphs or its failures. Such is the loyalty of fellowship. Loyalty only to that which is believed perfect is no loyalty at all.

During the past two years Dartmouth has been committed to an unprecedented effort to meet her most pressing capital needs through a comprehensive campaign for capital gifts. This past summer this world-wide appeal to the alumni and friends of the College reached its goal of $17,000,000. More will be received before the books of the Campaign are closed December 31. In addition, nearly $5,000,000 has been raised during this period toward the refounding and expansion program of the Dartmouth Medical School.

I have no heart for attempting to put the significance of this unique achievement into much the same words and phrases that are perforce repeatedly used in praise and appreciation of large undertakings. I do feel it is peculiarly fitting that the 1959 Convocation of the College should record the awareness of all who are committed to Dartmouth's welfare that her fellowship has magnificently met a task that only such a fellowship would dare set for itself. For some forty years the annual Dartmouth Alumni Fund has stood all but unrivalled as an example to the college world of widespread alumni support and now this pre-eminence has been paralleled by a Capital Gifts Campaign which before it is completed will have enlisted the support of upwards of 18,000 alumni, parents, friends, foundations and corporations.

A DECADE from this coming December 13, Dartmouth's renowned Charter will celebrate its two hundredth birthday. We are now one-third through the fifteen years we set ourselves in 1954 as a period of sustained rededication to the purposes of Dartmouth as the most meaningful way to prepare for the celebration of the College's bicentennial. The funds which have been raised in this Campaign will nurture every aspect of the institution as we move into what could be Dartmouth's most decisive decade. But beyond these dollars and behind the work of each teacher and student on this campus there stands today as a guardian of Dartmouth's cause a fellowship which even in its greatness has not before known an hour of such commitment as that which we honor here today.

Our institutions and their fellowships are the hardwon creations of men and women with a capacity for commitment. These strongholds of human aspiration sustain the individual in trouble and provide the advance bases from which are made the great forward thrusts to new knowledge and a truer community of humankind.

At Dartmouth these things are true for you and me in unique measure only because others in every generation kept the faith of Wheelock's commitment. And that faith still lives. Among us when we gathered here only a year ago were colleagues whom we now hold in honored memory because this commitment was in truth a part of them till death.

And now, men of Dartmouth, with pride in that of which we are here privileged to be a part, let us all once again remind each other:

Each of us is a citizen of this community and is expected to act as such; we are the stuff of an institution and what we are it will be; our business here is learning and that is up to each of us.

We'll be with each other all the way and good luck to us all.

Freshmen filled the side bleachers in the gym at Convocation.

Prof. Allen R. Foley '20 chats with two seniors at the coffee hourheld as an innovation this year after the opening program.

The funds which have been raisedin this Campaign will nurture everyaspect of the institution as we moveinto what could be Dartmouth's mostdecisive decade. But beyond these dollars and behind the work of eachteacher and student on this campusthere stands today as a guardian ofDartmouth's cause a fellowship whicheven in its greatness has not beforeknown an hour of such commitmentas that which we honor here today. — PRESIDENT DICKEY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN, -

Feature

FeatureCan Chinese Civilization Survive Communism?

November 1959 By WING-TSIT CHAN -

Feature

FeatureSocial Responsibility in Painting

November 1959 By CHARLES T. MOREY, -

Feature

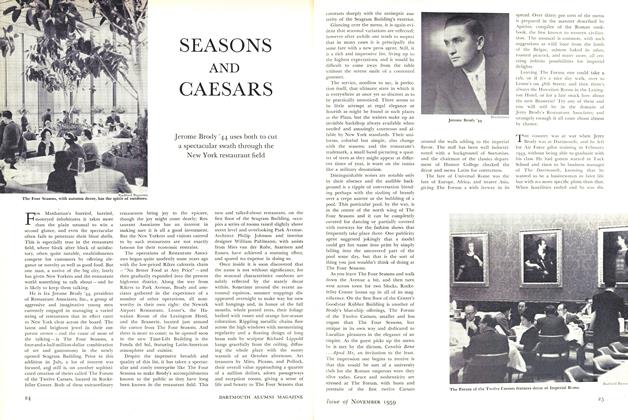

FeatureSEASONS AND CAESARS

November 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth and Saint Francis

November 1959 By GORDON M. DAY -

Article

ArticleHow I Conquered Alcohol

November 1959 By ALAN COOKE '55

PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY

-

Article

ArticleValedictory to 1955

July 1955 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Article

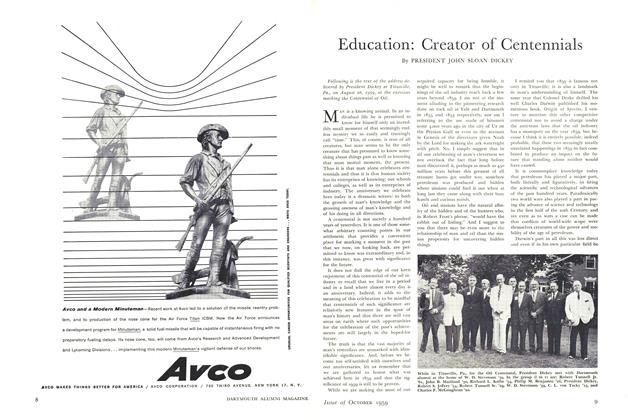

ArticleEducation: Creator of Centennials

October 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1961

July 1961 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1963

JULY 1963 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1964

JULY 1964 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1965

JULY 1965 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNervi Designs a Field House

May 1961 -

Feature

FeatureEvaluating Kitsch

November 1982 By Alan Gaylord -

Feature

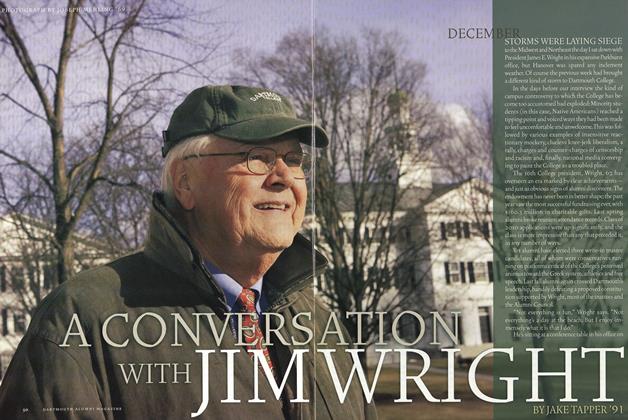

FeatureA Conversation With Jim Wright

Mar/Apr 2007 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Jan/Feb 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureThe Story of the Alumni Fund

March 1938 By LEON B. RICHARDSON 1900 -

Feature

FeatureA Heritage and An Obligation

JULY 1964 By SIGURD S. LARMON '14