Paradise Lost was the true cross-cultural experience.

Muddy, she pulls out boots and, when it's dry, she's got moisturizer. For four days her hair never mats, her clothes never muddy. At nightfall, while I'm gasping on the ground for air (in the same, smelly clothes I've been wearing for four days), she builds a fire, cooks a stew, and impresses the hell out of everyone. She knows who she is, who she wants to be. She's got her contacts lined up for internships, graduate school, and corporate life. The freshman trip is just one small step on her well-planned path to grownup life.

I, on the other hand, am regressing. I'm cursing everything and everyone. I hate Dartmouth, I hate hiking, I hate Nature. I hate my mother for letting me come. I hate myself for not remembering howmuch I hate exercise. My shoulders hurt from my frameless pack, my armpits sweat from my sticky leotard (Danskin, L.L. Bean—it all sounded athletic to me), my feet ache from my crummy sneakers. I cling to the rocks, asthmatically gasping for breath, sure I'm going to die. I'm thirsty, I'm hungry (every stew seems to be made with hotdogs and cheese, which-even at these altitudes—is a bit too treif for my taste). I hallucinate about home, Brandeis, kosher franks. I want to be anywhere but with these tough, Dartmouth types who think an eight-mile hike is a nice walk.

I admit it. It was my mistake. I signed up for the wrong trip. I overreached. I needed the artsy-Jewish-girl-who-never-really-exercised module. The one where you walk to Friendly's and get a shake. But, somehow, coming to Dartmouth, I wanted to fit in. I wanted to be that all-around college student who everybody wants on their team. I wanted to be that athletic, willowy blonde. So I plodded up the mountain, ate the green eggs, and sang "Men of Dartmouth," aching and shivering all the while. And, at the end of those four grueling days, grateful to be alive, I moved into my dorm—-just in time for Yom Kippur, the holiest (and that year, loneliest) day of the Jewish year. I attended services at Rollins Chapel (a decidedly new kind of shul) and broke my fast at Peter Christian's (not a particularly good omen). Still, I had visions of one day becoming part of the bigger, possibly better, Dartmouth culture. After a while, though, I realized that that culture had nothing to do with me. It wasn't about being female, it wasn't about being middle-class, and it certainly wasn't about being Jewish.

It wasn't that there were no other Jews at Dartmouth. It's just that no one was "out." We were like the gay community in the 1970s—except that I think they were less closeted. A wise alumni magazine editor once told me that everyone who went to Dartmouth will tell you that they didn't quite fit in. Everyone, from the football players to the fraternity boys, will tell you they were one of those creative loners President Freedman talks about. In retrospect, I guess that's possible. Especially in a school where such a high value is placed on belonging that you once found women singing "Men of Dartmouth." In Hanover, everyone's in such a frenzy to fit in that no one ever feels like they've really arrived.

For me, this was particularly true. I wanted to belong but I had no idea where or how to start. I had no "fitting-in" experience. I was a Jew from New Hampshire. I'd always been different. In Manchester, I never looked or acted like anyone. I had a nose like Barbra Streisand, didn't buy retail, and never tasted ham. Sure, I sang Christmas carols in school, but I only mouthed the word "Jesus" (an acceptable Jewish compromise passed down by my older brother). In Manchester, kids like me kept a low profile. We lived in a Catholic city where different spelled bad and the jury was still out on who killed Christ. People kept to their parish and to their own kind. So, rather than be ostracized, the Jewish kids learned to leave their mezuzahs at home and slip quietly into Protestant dances. Among ourselves we talked Bat Mitzvahs and Hebrew lessons. But among non-Jews we laid low. So I didn't come to Hanover expecting miracles. But I did expect a new kind of environment. I figured there'd be more Jews and more space to be Jewish.

Instead I found myself in a very male, very Christian place where there was little room to be female, let alone Jewish. I found few people who thought like me, had been brought up like me, or even looked like me. And, although ten percent of the student body was Jewish (far more than in my high school), there was little effort to identify, to say, "Dartmouth, here we are."

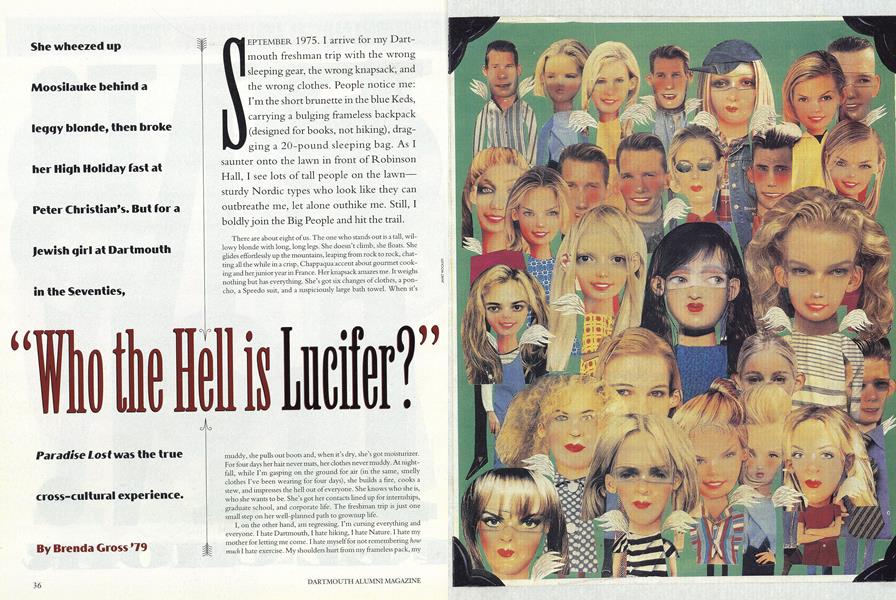

Rather, we all tried to straighten our hair, squeeze our Eastern European hips into men's Levi's, and look like Westchester coeds. The ideal was tall, thin, blonde, and flatchested. Only "natural" (read WASP) beauties need apply. No mascara, no blush, no curls, a far cry from my trip to Israel, where we all wore eyeliner to climb up Masada. For four years I felt very short, very bosomy, very brunette, very Ellis Island Meets the Ivy League.

Plus, there seemed to be a sense (even among the faculty) that everybody would know about Christian culture. Take freshman English, for example. The main text? Paradise Lost. I bought it. I read it. But I didn't get it. I didn't know who the characters were. I didn't understand the stories. The theological references escaped me. What Fall? What Sin? What Devil? I was a Jewish kid raised on Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. I knew nothing of angels, Satanic or otherwise.

Growing up in Manchester, you might assume that I had learned a lot about other religions. But like most kids I paid little attention to things that weren't about me. And my Hebrew school had no multicultural component. In fact, at Temple Israel, they circled the wagons lest we be tempted by tantalizing Christian images such as saints and Santa Claus. Among my non-Jewish friends, asking about the crucifixion was not considered polite, cross-cultural conversation. Thus, the only real ethnic exchange occurred at the annual Christmas pageant when six Jewish kids would sing "Dreidel, Dreidel" to a bewildered public-school audience.

So, to me, Christianity was a foreign culture. Paradise Lost was my first big trip abroad. Sin. Crucifixion. Guilt. Who the hell was Lucifer, I asked? It was all news to me.

As were the Jews at Dartmouth. Most of them came from New York and they were truly a different breed. At home, we stuck together, we knew we were different (and if we didn't know, the larger community was always more than ready to remind us). But the New York Jews were more laid back. Perhaps they took being Jewish for granted. Or perhaps they just had a different set of expectations. They had come to Dartmouth assuming that almost no one would be Jewish (looking forward to the novelty, maybe) while I had come thinking that ten-percent Jewish was a big step up.

I soon learned, though, that more than the percentages were against me. Dartmouth had no solid Jewish community. Jewish kids were so eager to "belong" that they literally ignored each other. They tried to blend, to dissolve into Dartmouth, to be more like other students. We might have been seduced by the idea of being Ivy League, by our now being admitted to a previously exclusive (non-Jewish) club. Flattered by inclusion, we didn't want to embarrass ourselves by clinging together, by being too vocal, by being "too Jewish." Maybe we figured if we were less noticeable, we would be more accepted. In this way, we were not unlike the women during the early days of coeducation who tried unsuccessfully to become part of the scenery.

So, we didn't speak up when classes were held on High Holidays or the Christmas tree went up. We accepted Thayer Hall's pathetic matzoh and hard-boiled eggs on Passover. We attended classes in Black Studies and Native American Studies but never really pushed for parallel courses in Jewish culture. We had a Jewish president who didn't talk about being Jewish, but we didn't let it bother us.

We didn't come together even to socialize. Looking back, I can remember very few Jewish couples at Dartmouth. Jewish guys didn't seek out Jewish girls but headed instead for the more standard (more inaccessible) Dartmouth beauties. Even if Jewish guys did come around, we girls barely noticed, mesmerized as we were by all those good-looking football-player types that surrounded us. Who was beautiful? Who was sexy? Anyone but our own kind.

Even the Jewish girls couldn't get it together. Like most women at Dartmouth in the early years of coeducation, we just didn't get it." We didn't realize that by coming together, by developing female friendships (versus chasing unresponsive men), we would make the college more woman-friendly, perhaps even more "Jewish woman-friendly." Instead, we kept running in circles, ignoring each other in search of the perfect (usually non-Jewish) guy.

By the time I left Dartmouth in 1979, more gays had come out, more feminists were getting a foothold, and more Native Americans were making their presence known. But being openly Jewish still hadn't caught on. We; and I include myself, still couldn't see the value in asserting ourselves, asking for what we needed. We still believed that we could melt into the pot. That we should take what we were given.

I'm 39 now and I've spent most of my adult life in higher education, as student and professor—four years at Dartmouth, two at NYU, five at the City University of New York, four at Columbia. Everywhere I go, I find the same thing: Asserting your Jewishness is in bad taste. Being gay is okay, being feminist is okay, being Latino or African-American is actually trendy. But being Jewish—or, at least, talking about it—is dangerous. It conjures up old stereotypes, pushes the wrong buttons.

So, Jews rarely make noise, at least about Jewish issues, in academia. Unlike other ethnic and political groups, they accept their concerns as marginal. Faculty meetings on Yom Kippur? No problem. Classes on Rosh Hashanah? We'll be there. We make a big effort not to ask for special treatment, lest someone think we're too powerful, too pushy, or just "too Jewish."

But times are slowly changing and Jewish students at Dartmouth and elsewhere are starting to assert themselves. They're less scared of standing out or stirring up anti-Semitism. Rather, they concentrate on what they need and on what needs changing. In doing so, they take the risk that not everyone will like them and accept the possibility that they may never really belong.

At Dartmouth in the 1970s, we weren't ready to take that risk. We wanted too badly to fit in, to become part of an Ivy League culture that promised status, success, conventional beauty, and most of all, belonging. We were light years away from the Lower East Side but like our immigrant grandparents we wanted to be real Americans, even real American aristocracy. So we gave up a little piece of ourselves, we became a "little less Jewish." We spent four years trying to "make nice," rather than making room for ourselves.

BRENDA GROSS writes in Bellmore, New York, whereshe has not once been seen wearing a backpack.

I overreached. I needed the artsy-Jewishgirl-who-never-really-exercised module.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

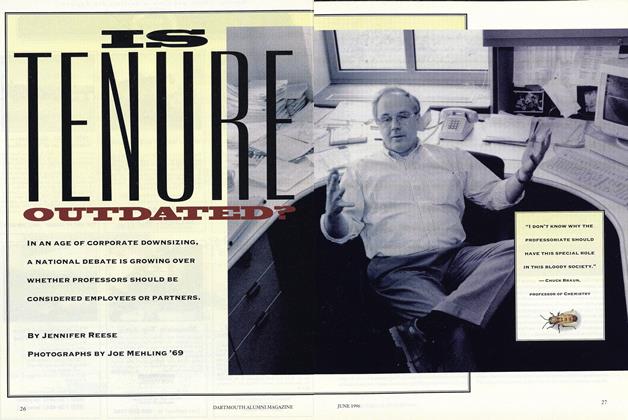

Cover StoryIS TENURE OUTDATED?

June 1996 By JENNIFER REESE -

Feature

FeatureNoble Boots

June 1996 By Chris Clarke ’75 -

Feature

FeatureAMEN! TO THE GOSPEL CHOIR

June 1996 By Suzanne Leonard ’96 -

Article

ArticleUnderground Reading

June 1996 By Kathleen Burge ’89 -

Article

ArticleOffice Hours

June 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe First Four-Minute Mile and the Last Coverup?

June 1996 By “E. Wheelock”

Features

-

Feature

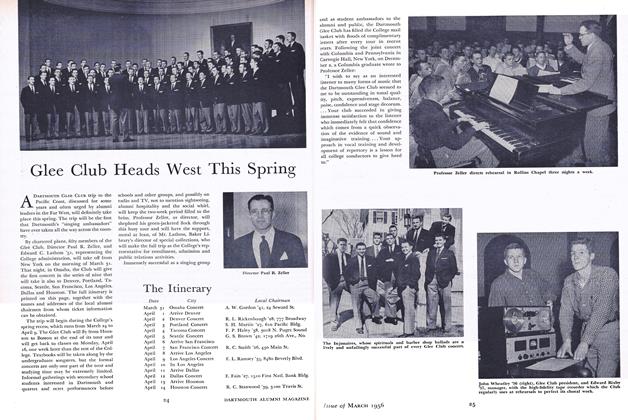

FeatureGlee Club Heads West This Spring

March 1956 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMurray Hitzman '76

March 1993 -

Cover Story

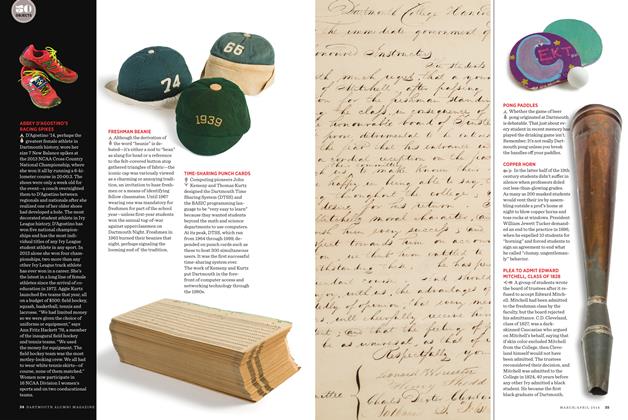

Cover StoryPLEA TO ADMIT EDWARD MITCHELL, CLASS OF 1828

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureInvocation

JULY 1971 By CHARLES F. DEY '52 -

Feature

FeatureRobert Frost Keeps Me Company Often Uninvited

APRIL 1984 By Kenneth Andler '26 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPeter Bien

OCTOBER 1997 By Robert Sullivan '75