Long Shielded by the Iron Curtain, once-forbidden books bring darkness to light.

ROXANA VERONA was 18, a university student in Bucharest, Romania, when she committed a crime against the Communist government: She read Doctor Zhivago. The Pasternak novel was banned in the Eastern Bloc, but Verona and her younger sister managed to borrow a forbidden copy for one night. Together they read it cover to cover.

Verona, a French professor who emigrated to the United States ten years ago, now teaches Dartmouth students some of the Eastern European literature she was forbidden to read in Romania: Franz Kafka, Vaclav Havel, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Romania's own playwright, Eugene Ionesco. She focuses on how Eastern Bloc writers overcame the ruthless censorship of the Communist Party—although some were exiled, tortured, even murdered.

In her strong Romanian accent, Verona starts by describing Stalin's poisonous influence on literature and art. Every year the Communist Party held a Congress of Cultural Affairs to dictate how artists should create. Writers were urged to produce novels that criticized laziness, foreigners, capitalists, and Americans. The novels had to extol the virtues of working for the state. The Congress even dictated acceptable story lines. "Usually the hero is the worker in the factory or in the fields, the peasant," Verona explains. "And then you have the negative element, sometimes a foreigner. In Bulgakov, there is always a foreigner coming into town and no one knows who he is. Foreigners are always individuals who are not to be close to."

In Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita, the foreigner who comes to town disguised as a magician is the devil. He brings a talking black cat, Behemoth, a name that has diabolical connotations in the Bible. But the devil turns out to be morally superior to the other characters, variously interpreted as Communist Party members or Russian citizens so caught up in daily hardships that they no longer have a sense of morality. Since Party officials in the Soviet Union had prohibited Bulgakov from publishing, The Master andMargarita did not get printed until after his death in 1966 and then in severely edited form. "You have to be brave to pass the message," Verona says. "You can have the commitment and not have the courage to write against censorship."

Verona speaks from personal experience. In Romania, everything she wrote—mainly papers on French literature-had to begin with a quote from Ceausescu. She fled Romania ten years ago with her husband, two daughters, and two suitcases after a neighbor told them their Bucharest apartment was bugged. They went to Vienna, then obtained political asylum in the United States.

According to Verona, many of the writers who remained in the Eastern Bloc attempted to avoid persecution by masking their message in fantasy. Writers resorted to fiction, allegory, even set their stories on other planets. A case in point: Kafka's famous story "Metamorphosis," in which a man wakes up one morning to find he has turned into a huge bug. Eastern Bloc readers understood the message. "They knew that the bug in the middle of the family, this bug was not a real bug," says Verona. "It's someone who wants to distance himself from everyday life. This is a way of protest." Kafka, a Prague insurance clerk whose writing was not published until after his death, returned often to the theme of alienation. Says Verona, "He speaks about everyday life, how the human creature is overwhelmed by red tape, by the institution."

Ionesco's The Rhinoceros also uses fantasy to chart the alienation of the individual. "Everyone starts to become a rhinoceros," Verona says. "The only one who is normal is the one who is not a rhinoceros. And then, the normal one becomes a monster because he is alone and the others are rhinoceroses." Is it just a story or a commentary? As Verona puts it, "It could be about the Nazis, it could be about the Communists."

Indeed, the cryptic element of fantasy simultaneously repels and invites interpretation. "Sometimes, those stories are more incendiary than the reality," Verona says. "You can say things that are more dangerous." That is also why the Party routinely persecuted writers. Bulgakov died in obscurity. Havel, also a political dissident, was jailed for five years. Vladimir Mayakovsky, a Russian poet, committed suicide, in part because the Party censored him.

Verona also looks at how Eastern European writers struggled with questions of identity. Kafka, for example, was Jewish, but as an intellectual and writer he felt alienated from other Jews in Czechoslovakia. "His ego was split," Verona says. "All his life was in a way obsessed with his condition: Who am I?"

The struggle of Eastern Bloc writers to get their message out is why Verona, who was shy about lecturing in English when she first arrived at Dartmouth, felt compelled to teach this literature to American students. "All this effort," the professor says, "for communicating with the rest of the world."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

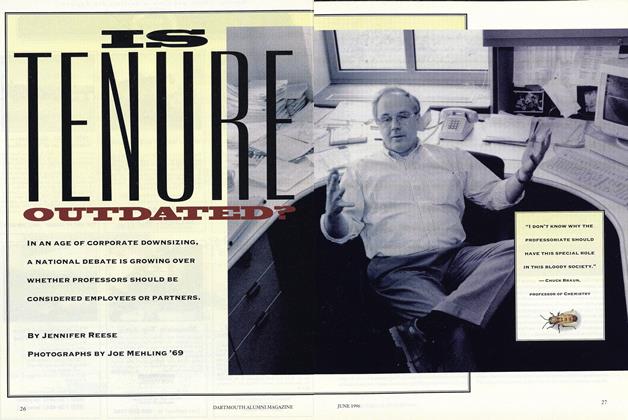

Cover StoryIS TENURE OUTDATED?

June 1996 By JENNIFER REESE -

Feature

Feature“Who the Hell is Lucifer?”

June 1996 By Brenda Gross ’79 -

Feature

FeatureNoble Boots

June 1996 By Chris Clarke ’75 -

Feature

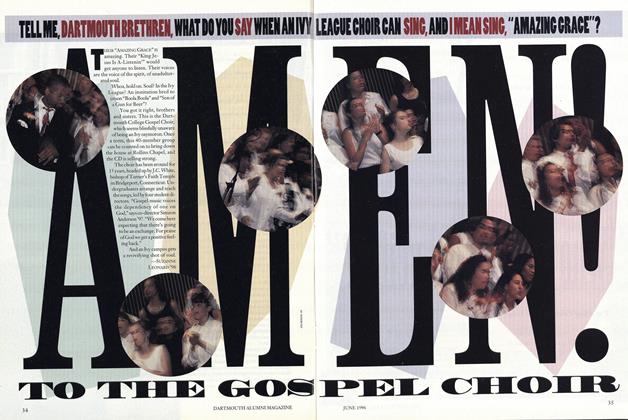

FeatureAMEN! TO THE GOSPEL CHOIR

June 1996 By Suzanne Leonard ’96 -

Article

ArticleOffice Hours

June 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe First Four-Minute Mile and the Last Coverup?

June 1996 By “E. Wheelock”