Once upon a time, getting into medical school was a safe bet lor a certain future. Times have changed.

When Emily Smith '97 completed her sixteenth and final medical school application last fall, she was not relieved. The hardest part of the process was just beginning. "Since birth I have wanted to be a doctor," Smith says. "For the first time I had to think about other careers than medicine."

With competition for medical schools around the country at record levels, nearly 30 percent of Dartmouth's hundred aspiring doctors will face one of senior year's bleakest realities: the rejection letter. And not just one, but 16. That s the average number of medical schools to which a senior applies.

Smith is nervous about her GPA of 3.4. The average GPA for students accepted at most of the nation's medical schools is 3.5. At Dartmouth Medical School it's 3.6. "There are a lot more qualified students than me," Smith admits. "I worry that they are applying to middle-of-the-road schools and taking spots that would be available to me. Realizing that I could do other things in my life was a real revelation to me." Smith says she could go into teaching or another form of graduate study, but she does not like talking about these options.

A decade ago premeds like Smith could be more optimistic. When only 53 Dartmouth seniors applied to medical schools in 1988, more than 85 percent made it in. Since then the number of Dartmouth seniors applying has more than doubled. 1 he national competition has intensified, with nearly 47,000 applicants vying for 17,357 available spots—a 7 5 percent increase in applications since 1989. Applications to Dartmouth Medical School have nearly doubled since the late 1980s. Lastyear, 6,000 applicants fought for 87 available spots in its entering class, making DMS one of the country's most selective medical schools. Dartmouth undergraduates have a small home court advan tage when applying to DMS. Of the 172 Dartmouth seniors and recent alumni who applied last year, the medical school admitted 25. Smith hopes this will work in her favor.

What explains the competition, which comes at a time when health care reforms such as managed care are reining in physicians' salaries and their traditional independence in prescribing and delivering patient care? "Calling your own business shots and being able to practice medicine from your own standpoint are gone," says Dartmouth-Hitchcock gastroenterologist Peter Anderson '69, in a lament familiar to current doctors. But such changes do not seem to be deterring students from wanting medical careers.

Some observers say that student interest is still a matter or economics. "Medicine looks like a pretty good field at a time when Ph.D.'s, lawyers, and dentists have been a glut on the market," says Dr. Harold Friedman, chair of Dartmouth Medical School's admissions committee. Boston cardiologist Bob Thurer '67 agrees that "It's a safe haven. If you have an M.D. degree you'll never be out of a job." And it's a job with stillhealthy wages: The median net income for physicians is more than $150,000 a year.

But Dr. C. Everett Koop '37 says students are following a more caring motive. Head of Dartmouth's Koop Institute, the former mer surgeon general asserts that today's students are more concerned about others than they are about finances. "The current medical students are a different breed," he insists. "They feel a calling to medicine, to serve the underserved."

"The intensity of commitment among premedical students is really high," agrees Joe Walsh '84, a health-sciences graduate student who studied the premed phenomenon at 11 New England colleges. "Most students whose family members were doctors had been told not to go into medicine. But these students were committed to going into medicine anyway."

Declares Emily smith,"I don't know who's going to be paying my salary, or how much I'm going to be making, but I know that whatever I'm going to be doing, I am going to be satisfied with the fact that I am a physician and that I am healing people." She scorns the notion of choosing medicine because of its high salaries. "If you can't say to yourself, 'No matter what happens in health care I'm going into it,"' she says, "then you don't belong in it."

"It's a profession, but it's also giving to the community," adds Ellen Sullivan '97, a senior interested in women's health.

"Medicine is a very noble intent," says John Peoples '96. Having discovered his calling to medicine late towards his senior year, after caring for his aging grandfather Peoples is packing in the premed classes he missed at Dartmouth during a two-year post-graduate program at Columbia. "Medicine is a career that's a lot of hard work, but it's a respected position no matter what the pay. I feel like I can live the lifestyle I want to and not compromise, that I can still do something of value for society."

Nonetheless, today's premeds will encounter a very different job market than the one 1980s medical students entered. During the last decade, specialty practices have reigned as the hot medical professions. Big bucks and high prestige accompanied specialist careers, and the generalist, says Anderson, was considered a "second-rate citizen." Today, a surgeon earns roughly $220,000 a year, twice the salary of a family physician, but the gap is narrowing. Researchers at Dartmouth's Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences estimate that there are 100,000 too many specialists. Meanwhile, the demand for generalists is rapidly increasing. Health-care plans are increasingly requiring patients to see a family physician for referral to a specialist. The goal is twofold: to help reduce costs by eliminating unnecessary visits to high-priced specialists, and to make the generalist the regular consultant for personal health care. Some specialists understandably view the increased emphasis on generalists as a threat Anderson reports that there are even classes to help specialists retool as generalists but many premeds see it as good news. Most students say they want a continuing relationship with their patients, and nowhere is this more possible than as a generalist. To accommodate the demand for morgeneralists, medical schools are revising their curricula. In 1995 Dartmouth Medical School introduced a required family medicine course, and admissions is turning a favorable eye toward generalist-oriented applicants.

But it is a long academic road between the Green and the medical school. According to graduate-school advisor Susan Wright, Dartmouth's premed track is one of the most rigorous and committing programs on campus. Not really a major, the premed route is a set of courses which medical schools require for admission. In addition to completing their ma jors and the College's distributive courses, premeds must complete at least ten other prerequisite classes to even be considered by medical schools: two terms of physics, two mathematics, two or three biology, and four chemistry, including the notorious two-term organic chemistry.

ago, she had already started planning her course schedules to ensure time for a sophomore-term language-study abroad in Spain. Since Smith is an anthropology major, none of her classes overlapped with her premed requirements. (Most students major in chemistry or biology, conveniently melding several of the pre-med requirements into their majors. Medical schools, however, look to accept a range of majors, so majoring in chemistry or biology is not necessarily an advantage. Onethird of students accepted to Dartmouth Medical School are non-science majors.) Of the 35 courses required to graduate, Smith took not a single elective. She de When Smith matriculated four years voted ten courses to her major, ten to her Spanish minor (which included the foreign-study term in Madrid), one to her freshman seminar, and four to her social science distributives. She filled the remaining ten slots with her premed requirements. "Somehow," Smith says, "I managed to do things that most premeds don't do. A lot of premeds hole up."

The surge in premeds affects more than the sciences. According to off-campus programs director Peter Armstrong, the college's language study abroad programs are experiencing some of the lowest enrollment numbers in recent history, partly because of the increasing numbers of students who cannot interrupt premed studies. Last fall, the college had to cancel three foreign-study programs.

Premeds may miss such opportunities, but, according to biology professor Thomas Roos, they get something that other students do not: a liberal education. "The only students at Dartmouth who we can really guarantee have a liberal education are premed students," he asserts. "You don't have a right to call yourself liberally educated unless you are educated in the sciences: physics, bio, chemistry. Not studying science is every bit as bad as not knowing Shakespeare or Homer."

The sciences, Roos says, give students a deeper understanding of the human body. "I don't think you become a more humanistic-oriented physician by taking more English courses. You get it by taking more chemistry and biology classes. You learn what happens when you kick a soccer ball the wrong way and twist your knee. For nutrition issues, for example, unless you know what happens and where it happens, your comments aren't worth a plate of beans."

Another large chunk of premeds' undergraduate education comes from off-campus internships. Premeds are notorious for racking up exotic internships and volunteer projects it's a way to gain practical experience in.medicine and to bolster the resume. By the time Smith completed her 16 applications last fall, she had served four separate internships: one as a pathology lab assistant in Pennsylvania; one doing respiratory re-search search at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center; another studying leaf-cutter ant colonies at the Montshire Museum of Science in Norwich, Vermont; and the last as a summer research intern studying cervical cancer at the National Institutes of Health.

But of all the projects seniors have completed by this year, Rachel Wellner's tops them all. Wellner, a '97, has never done things in moderation. By the end of her sophomore year she had completed 12 premed courses and taken her MCAT exams (most students don't complete these requirements until a fall year later). With those behind her, she began organizing the largest international volunteer project ever done through Dartmouth: a community health project in Ocotal, Nicaragua.

Ten Dartmouth student volunteers spent two months last winter living with families in the small town, dispensing medical supplies to health-care clinics and teaching hygiene, nutrition, and sexual education. Wellner, sponsored by Dartmouth's Dickey Center and Tucker Foundation, marshaled the volunteers from campus and raised $65,000 in funding and medical supplies (including $20,000 in latex gloves for the region's needy health-care clinics).

Some envious students wonder if Wellner organized this project just to beef up her medical school application. "No way," she asserts "I could have worked in a fancy lab for a lot less effort. I put myself through hell," she says. "Getting into med school just isn't a motive for me to do so much work. It's not a matter of showing off. I did it for myself." When Wellner applied early to the University of Connecticut medical school last year, the admissions committee had never seen a project like hers. During an admissions visit, Wellner was seated next to another prospective student who asked the admissions committee what he needed to do to get accepted. An admissions staffer replied by holding up Wellner's Nicaragua brochure: "This," he said. Wellner was the first student among her Dartmouth mouth classmates accepted to medical school. During her junior winter term, UConn invited her in a full year before most others are accepted.

Most Dartmouth premeds, though, spent this winter nervously approaching their mailboxes each day. Rejection from medical school is one of the premed's greatest fears. The anxiety accompanies all premeds through their four years here during each test, through internship applications, and during MCAT preparations. With competition for medical school at cutthroat levels, every test counts, and every point on the MCAT scores will be closely evaluated by admissions committees.

To ensure good MCAT scores, Emily Smith pushed her studying level to the brink of exhaustion. "During my junior winter I developed the skill of falling asleep at my desk," Smith says. In addition to studying for the MCATs and taking a difficult premed biology class along with two other courses, she was also the president of Sigma Delta sorority and an editor of a campus feminist paper, Spare Rib. Each morning she would wake by 7:45 for a bowl of Grape Nuts and yogurt before 8:30 class, taking "a big huge mug of coffee to get me through biology." Between five weekly sorority meetings, two MCAT prep classes, and afternoons spent giving admissions tours or working for Spare Rib, Smith rarely had time for studying during the day. "There were nights when I would get an hour of sleep. I would doze off for ten minutes, then suddenly wake up, out of fear of not studying for the MCATs."

The ten premed classes on campus do nothing to alleviate premeds' stress levels, either. Especially the biology and organic chemistry courses. Organic chemistry is a weed-out class, and is dreaded more than any other premed class on campus. "It's not an enjoyable feeling to know that you're determining someone's fate," says organic chemistry istry professor John Bushweller. "But this may be the first indicator that things may or may not work out in the long run. The nature of the learning you do is similar to medical school: a large volume of work, and cumulative knowledge."

Premed classes even feel different from others: the front-row seats, normally abandoned in other classes, become coveted positions by students wanting to look attentive; the premeds are distinguished by their four-color click pens which quickly snap from blue to red and green to black when labeling graphs; and the classroom is dead silent when the professor begins to speak. Also, wait until the grades come back from the first test: more than 100 grade-hungry students just devoted most of their weekend to studying for it, but the bell curve simply doesn't allow for more than a few A's. "Premed classes easily require twice as much time, probably three," Smith says.

The competition affects both sides of the lectern. "There's a lot of hostility from professors towards premeds," Ellen Sullivan says. "Teachers don't like us because we're not pleasant to teach. We're so cutthroat."

One of the students who weeded herself out early is Marcie Handler '97, an anthropology major. She took two premed chemistry and math courses her freshman year, but it wasn't bad grades that pushed her out. "There was no personal attention, and it was horribly competitive," she says. "I ended up dropping the premed."

Despite the competitive road for students, the selection process has its benefits. The undergraduate cut may be the most difficult hurdle, but it guarantees a motivated crop of doctors on the physician track. Many doctors believe that the competitiveness of today's premeds will translate into hard work toward improving the quality of health care. "We're going to have a kinder, gentler medicine," predicts Koop.

Nearing the end of her premed years, Emily Smith received a string of rejections, including Dartmouth Medical School. ("I stopped counting after six," she says.) But the Medical College of Pennsylvania at Hahnemann sent her a letter of acceptance. Now she faces eight to 12 years of training and a medical-school debt likely to top $75,000.

Emily Smith, future M.D., considers herself lucky.

Emoily Smith '97 is one of 47.000 prenteds vying for 17.000 stots.

Organic chemistry elevates stress levels for hopeful '99s Todd Weller and George Braun.

jump-starting her career,freshman intern Angela Poppeassists Dartmouth-Hitchcock Robert Harris

Premed classes feel different from others. With competition for medical school at cutthroat levels, every test counts.

Premeds are notorious for racking up internships and volunteer projects to gain experience and holster the resume.

TYLER STABLEFORD is photography and copy editor at Climbing magazine. He lives in Aspen and has no premed worries.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMountain of Ghosts

June 1997 By WD. Wetherell -

Feature

FeatureCleaning Up La

June 1997 By Jim Newton '85 -

Article

ArticleOf Appointments and Disappointments

June 1997 By "E. Wheelock." -

Article

ArticleA Cubicle of One's Own

June 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1993

June 1997 By Christopher K. Onken -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

June 1997 By Brooks Clark

Tyler Stableford '96

-

Article

ArticleThe Next Athletic Facility: An Indoor Imitation of a Cliff

Winter 1993 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Article

ArticleOkay, Now Bounce

November 1994 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Article

ArticleOn June 23 choreographer Moses Pendleton '71

October 1995 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Cover Story

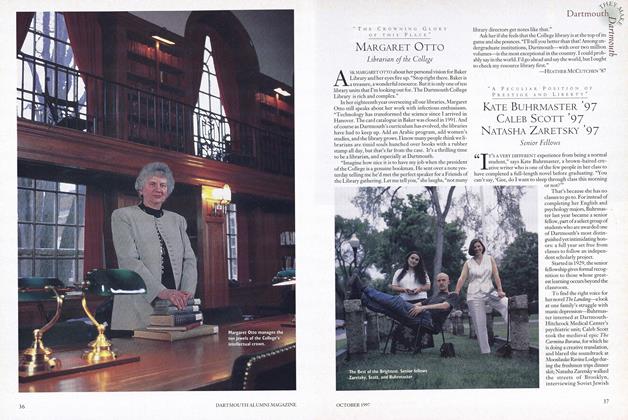

Cover StoryKate Buhrmaster '97 Caleb Scott '97 Natasha Zartsky '97

OCTOBER 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Cover Story

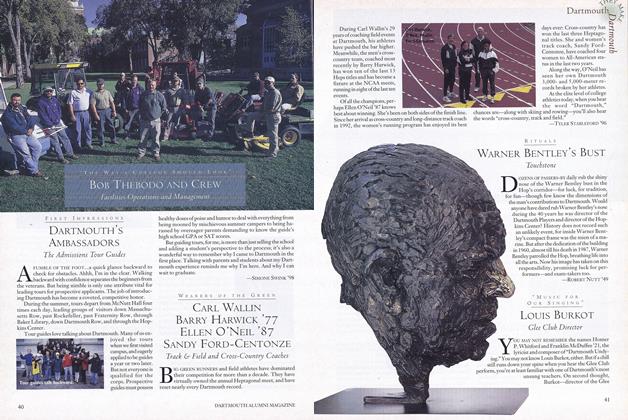

Cover StoryCarl Wallin Bary Harwick '77 Ellen O'Neil '87 Sandy Ford-Centonze

OCTOBER 1997 By Tyler Stableford '96 -

Photography

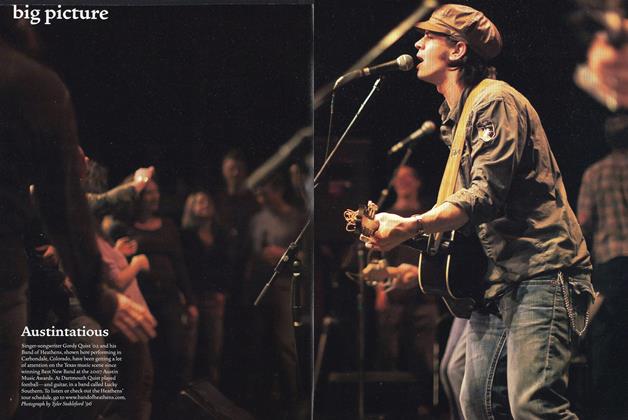

PhotographyBig Picture: Austintatious

Sept/Oct 2008 By Tyler Stableford '96