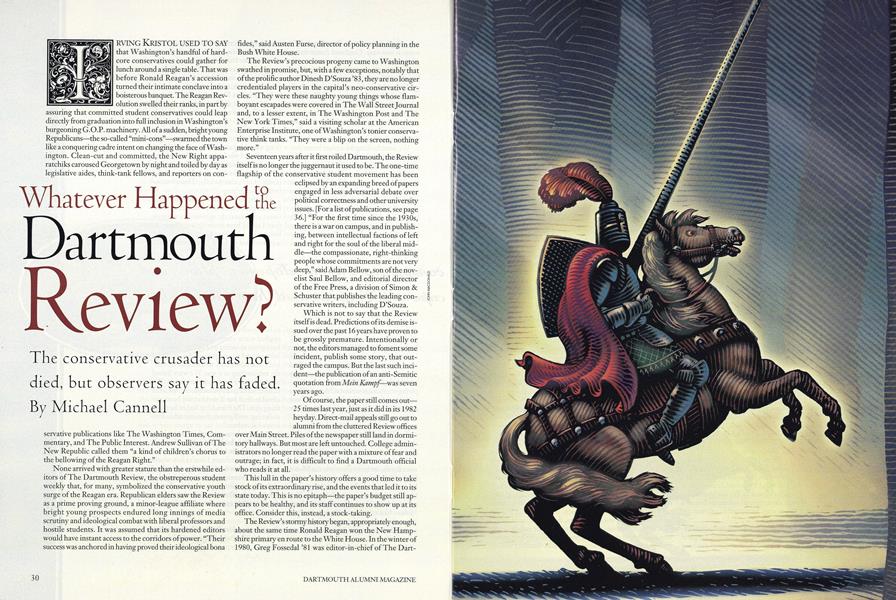

The conservative crusader has not died, but observers say it has faded.

RVING KRISTOL USED TO SAY that Washington's handful of hardcore conservatives could gather for lunch around a single table. That was before Ronald Reagan's accession turned turned their intimate conclave into a olution swelled their ranks, in part by assuring that committed student conservatives could leap directly from graduation into fall inclusion in Washington's burgeoning G.O.P. machinery. All of a sudden, bright young Republicans—the so-called "mini-cons"—swarmed the town like a conquering cadre intent on changing the face of Washington. Clean-cut and committed, the New Right apparatchiks caroused Georgetown by night and toiled by day as legislative aides, think-tank fellows, and reporters on conservative publications like The Washington Times, Commentary, and The Public Interest. Andrew Sullivan of The New Republic called them "a kind of children's chorus to the bellowing of the Reagan Right."

fides," said Austen Purse, director of policy planning in the Bush White House.

The Review's precocious progeny came to Washington swathed in promise, but, with a few exceptions, notably that of the prolific author Dinesh D'Souza '83 they are no longer credentialed players in the capital's neo-conservative circles. "They were these naughty young things whose flamboyant escapades were covered in The Wall Street Journal and, to a lesser extent, in The Washington Post and The New York Times," said a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, one of Washington's tonier conservative think tanks. "They were a blip on the screen, nothing more."

Seventeen years after it first roiled Dartmouth, the Review itself is no longer the juggernaut it used to be. The one-time flagship of the conservative student movement has been eclipsed by an expanding breed of papers engaged in less adversarial debate over political correctness and other university issues. [For a list of publications, see page 36.] "For the first time since the 1930s, there is a war on campus, and in publishing, between intellectual factions of left and right for the soul of the liberal middle—the compassionate, right-thinking people whose commitments are not very deep," said Adam Bellow, son of the novelist Saul Bellow, and editorial director of the Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster that publishes the leading conservative writers, including D'Souza.

Which is not to say that the Review itself is dead. Predictions of its demise issued over the past 16 years have proven to be grossly premature. Intentionally or not, the editors managed to foment some incident, publish some story, that outraged the campus. But the last such incident—the publication of an anti-Semitic quotation from Mein Kampf-was seven years ago.

Of course, the paper still comes out— 25 times last year, just as it did in its 1982 heyday. Direct-mail appeals still go out to alumni from the cluttered Review offices over Main Street. Piles of the newspaper still land in dormitory hallways. But most are left untouched. College administrators no longer read the paper with a mixture of fear and outrage; in fact, it is difficult to find a Dartmouth official who reads it at all.

This lull in the paper's history offers a good time to take stock of its extraordinary rise, and the events that led it to its state today. This is no epitaph—the paper's budget still appears to be healthy, and its staff continues to show up at its office. Consider this, instead, a stock-taking.

the country's oldest student newspaper. He had distinguished himself as a sharp, ambitious reporter during his rise from sports editor to the top editorial post. "There was no question that Greg was going to get that job," said Patricia Berry '81, then literary editor. "When Greg set out to do something, it was a mission. He took the paper by storm."

FOSSEDAL PREVAILED but his abrasive, arrogant manner inhibited friendship. "He was one of the brightest people around, and he wrote the most incredible poetry," Berry said. "But he was tragically flawed; there was something off about him. Out of nowhere would pop this meanness, this bad behavior. My sorority friends thought I was crazy to hang around someone like Greg."

When the editorial-page editor objected, Fossedal fired him. It wasn't the first time Fossedal had, in the staffs opinion, improperly imposed his own politics. They sent a petition of complaintto the publisher, Chuck Nordhoff '81, who fired Fossedal.

The ousted editor was not without campus support. Fossedal belonged to a circle of conservative Catholic students who frequented Aquinas House, the Catholic student center, and deplored the pieties of the academic left over drinks at the Hanover Inn. This small dissenting society included Ben Hart '81, founder of Students for Reagan, and Michael "Keeney" Jones '82, whose columns in The Dartmouth tweaked what he called "approved views." Jones, in particular, had a gift for the outrageous contrarian gesture. While most students wore blue jeans and hiking boots, he affected the dress of a bygone Ivy League: bow-ties, white oxford shirts, gold-buttoned doublebreasted blazers, and penny loafers. Instead of beer, he sipped champagne. "All of them had read Brideshead Revisited," said D'Souza, then a freshman contributor to The Dartmouth, referring to Evelyn Waugh's sentimental tribute to Britain's Catholic aristocracy. "They were interested in cultivating a certain attitude and style."

That style was characterized by an aversion to modern culture. They gravitated to courses that emphasized the great thinkers like Dante and St. Thomas Aquinas. Jones designed his own major which drew upon no material later than about 1600 A.D. "All of them were straight-A students, but they flew off the handle when they encountered issues outside the Middle Ages," said Professor Charles Wood, who taught them medieval history. "They reacted irrationally."

Shortly after Fossedal left The Dartmouth, the conservative circle concocted a plan over champagne to launch an alternative weekly that would, in their words,, "give alumni and students a conservative view of things." Composed in the biting, overdy partisan style of The American Spectator, their rogue startup would challenge what Fossedal and his confreres saw as an entrenched liberal orthodoxy on campus. In homage to their guru, William F.Buckley Jr., founder of The National Review, they christened their paper The Dartmouth Review. "We had the working knowledge and technical skill," said Jones. "We had the ideological focus. Above all, we wanted to have fan. It was college."

Dinesh D'Souza and three other staffers, including Jones, defected from The Dartmouth to join them. Within two weeks, they composed a 12 -page tabloid with a column by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a short article by Buckley, and an interview with John Steel, who won his election by 2,000 votes. Their debut issue appeared just in time to distribute free to graduates and their families as they filed out of Commencement.

From its inception, the Review demonstrated a merciless instinct for antagonizing liberal sensibilities. Its editors advocated an old-fashioned curriculum focused squarely on the recognized canons of Western civilization while ridiculing what they called "oppression courses" that cater to gays, feminists, and minorities. Its searing, sarcastic voice exhorted administrators to roll back "grievance-based" programs, like affirmative action, that in their view afforded minority students "preferential treatment" and lowered academic standards. In short: they extolled the virtues of an older, decorous Dartmouth they themselves had never known, where white men attended daily chapel and professors taught the classics.

The Review emerged as an odd, inverted flashback to the days when student activists abetted by outside agitators conspired to outrage the college establishment with satire and shock tactics. Only this time, the merry dissidents deployed their guerrilla attacks from the right. This was Reagan's Revolution, not Che Guevera's Publications from Rolling Stone ("College papers Do the Right-Wing Thing") to The New Republic ("The Dartmouth Wars") treated subversive campus conservatives as a newsworthy departure from the accustomed order.

Naturally, the Review earned warm support from grownup conservatives. The editors sent their debut issue to Jack Kemp, Patrick Buchanan, William F. Buckleyjr., and R. Emmett Tyrrell, editor of The American Spectator. All agreed to serve on the Review's advisory board. The emergence of a vigorous conservative voice on campus, the last bastion of 1960s-style thought, was sweet vindication for those true believers who had upheld conservative principles throughout its unfashionable years. What the national media found at Hanover was, in truth, the result of a personalized squabble among intramural factions. But ardent patrons like Bill Buckley and Ben Hart's father, Jeffrey Hart '51, a Dartmouth English professor, syndicated columnist, and National Review contributor, portrayed the students to a national readership as collegiate Freedom Fighters engaged in valiant resistance against an institutionalized left. ("Throw a bomb," the elder Hart exhorted. "See what happens.") As a result, the Reviewers enjoyed prominent coverage in reams of articles and editorials analyzing the change in political consciousness. National reporters solicited the Review when it needed a quote from Reagan youth. Phil Donahue and David Susskind invited the Reviewers to expound on their counter counter-revolution.

Disgruntled alumni, some of whom had suspended donations to the College, gave generously to the Review. Within a year it collected $106,000, according to Ben Hart's booklength account, Poisoned Ivy. The widow of a wealthy Beverly Hills alumnus sent a check for $10,000. The same amount arrived from the John Olin Foundation. "Subscriptions began to pour in by the hundreds, not only from alumni, but also from people outside the Dartmouth community, who wanted to see what all the fuss was about," Hart wrote.

FROM TWO CLUTTERED ROOMS over a hardware store on Main Street furnished with photographs of Nixon, Reagan, and Buckley, the Review concocted assaults laced with a baiting, sarcastic edge. In 1981 it printed a confidential roster of the College's gay student group. In reaction, undergraduates staged a protest rally on the Green. Reviewers dressed in foppish Gatsby garb held a croquet tournament nearby. Between shots, they sipped gin-and-tonics and nibbled finger sandwiches catered by the Hanover Inn. It was an effective bit of theater: the Reviewers deflated the protest by luring away some of its participants. When students voluntarily fasted in observance of Oxfam World Hunger Day, the Review hosted a champagne and lobster salad lunch—sending proceeds to Mother Theresa. And they upstaged a Veteran's Day anti-war rally on the Green by blaring Sousa marches from dorm windows. They challenged College funding for the Gay Students Alliance by trying to procure money for "The Dartmouth Bestiality Association."

The Review disarmed its targets with a brazen humor that flouted the niceties of conventional campus discourse. Editors described one College official, for example, as suffering from "a robin's nest hairdo and the personality of an electric chair." They gave freshmen free Dartmouth Indian T-shirts a decade after the Trustees renounced the mascot as racist (a practice the Reviewers still follow). And they arranged for a black student to conduct a phone interview with David Duke.

The Review's adversarial tactics deliberately punctured the College's prevailing civility. In March 1982, for example Jones ridiculed the College's affirmative action program with a parody of black dialect entitled "Dis Sho Ain't No Jive, Bro" which said, in part: "The 'ministration be slashin dem free welfare lunches for us po students. How we pused to be gettin' our GPAs up when we don't be havin no food?" Jack Kemp judged the article "in extremely poor taste" and resigned from the advisory board. "A lot of us had that carefree feeling at Dartmouth," remembered Patricia Berry. "It was a place where people smiled at one another. Then it changed: everything wasn't goodness and light, after all. There was a lot of anger on campus. The Review made people furious—I mean furious. We realized there are some objectionable people out there, and some are right here in our front yard."

However menacing, the Review's nervy, derisive humor proved infectious (Buckley called it "a right-wing National Lampoon"). Clones sprang up at some 50 other colleges and universities, including all the Ivy League campuses. Even Berkeley produced a version. None were as adversarial as The Dartmouth Review, but they shared its conviction that political correctness leads to flaccid standards.

Established conservatives mustered philanthropic resources to help the proliferating papers, largely under the auspices of the Institute for Educational Affairs, a think tank started by former Treasury Secretary William Simon and Irving Kristol editor of The Public Interest, a neoconservative policy journal. In part, the lEA served as exchequer for conservative underwriters like the John Olin Foundation and the Coors brewing family. It began in 1979 by helping John podhoretz son of conservative author Norman Podhoretz, publish Counterpoint at the University of Chicago after the mainstream campus paper refused to print his review of Apocalypse Now. By the mid-1980s the lEA was issuing grants of about $1,500 to more than 30 student startups. It also ran regional workshops where aspiring young editors learned practical skills like production and advertising sales. It even provided a newsletter with story ideas and dispensed advice over a toll-free hot line.

The Dartmouth Review never needed much outside help. As the vanguard of a conservative youth movement, it followed its own course. In the mid-1980s, it was led by two tough, outspoken women: Debbie Stone '87 and Laura Ingraham '85. "To Greg [Fossedal] and Keeney [Jones], the Pope was an object of austere reverence," said D'Souza, "but to Debbie and Laura, two Protestant women, he was just a cute man in a dress. They had a different style—a different reading list—but the same agenda." Under their stewardship the emphasis shifted from the founder's sly, subversive tone to a series of ad-hominem confrontations. At 2:45 on the morning of January 21, 1986, hours after the College observed the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, 12 students—including ten Reviewers—unloaded sledgehammers from a rented U-haul and demolished four shanties constructed by anti-apartheid protesters. "We picked up some trash on the Green," freshman Chris Baldwin '89 boasted to Newsweek.

As often happened, the campus uproar helped attract reporters. The Associated Press, for example, photographed a bed sheet hung from a tree that said, "Racists Did This." Students launched a sixties-style occupation of College President David McLaughlin's office and sang "We Shall Overcome." The siege ended when McLaughlin canceled classes for an all-day teachin. "These kids were singing the same songs I remember from college," said Alex huppe then College spokesman. "It made a delicious story." In October 1988, the Review printed a column headlined "Ein Reich, Ein Volk, Ein Freedman that

depicted McLaughlin's successor, James Freedman, who is Jewish, as a Hitleresque dictator who advocated a "Final Solution to the Conservative Problem" at Dartmouth. A front-page cartoon in the next issue portrayed Freedman in a Nazi uniform and Hitler mustache. The Trustees sent a letter to students and faculty denouncing the editors for "ignorance and moral blindness." A group of faculty sent Bill Buckley a letter asking him to disassociate himself from The Review. He replied that the Review "published a caricature, designed to make their point, which is that the Administration of Dartmouth is tyrannical."

Meanwhile, the irrepressible Review ran relentless attacks on the teaching style of black music professor Bill Cole, author of books on Miles Davis and John Coltrane and founder of a world music program. Laura Ingraham (who later clerked for Justice Clarence Thomas) described Cole as a "used Brillo in a 1983 piece headlined "Bill Cole's Song and Dance Routine." Cole filed a $600,000 libel suit against the Review. He dropped the suit after the Review agreed to print an apology. It never did.

On the contrary, the Review persisted in badgering Cole. A 1988 piece ridiculed him as a flaky, incoherent lecturer presiding over "one of Dartmouth's most academically deficient courses." Four Reviewers armed with a camera and a concealed tape recorder confronted Cole as a class dispersed. They came to solicit his reply, but their posture struck him as threatening. When they refused to leave, an enraged Cole called them racists and flailed at them. No blows actually landed, but Cole did break a flash as one Reviewer snapped a close-range photograph of him. The students also recorded the encounter without Cole's knowledge. (A disciplinary committee suspended three of the four students for "vexatious oral exchange." They, in turn, hired a lawyer with financial help from the John olin Foundation and took the case to court. A New Hampshire superior-court judge ordered Dartmouth to reinstate them.)

Cole quit in 1990, blaming the Review for driving him away. His resignation made national news, including a segment on 60 Minutes. Not everyone at Dartmouth was as volatile as Cole, but it was, in general, a thinnerskinned institution than it is today. "Dartmouth was somewhat insecure," said Professor Charles Wood. "People didn't know where the College stood through these highly individual attacks. President McLaughlin had tried to stay clear and not make any statements. He didn't address the subject during faculty meetings. Instead, he tried to be gentle: maybe if we're nice the Review will return to the fold."

By most accounts, a turning point came when President Freedman delivered a special address to the faculty on March 28,1988. He defended the paper's right to publish, but warned that "the Review is dangerously affecting—in fact, poisoning—the intellectual environment of our campus.

Observers credit Freedman with shoring up Dartmouth's self-image as a community of scholars unruffled by innuendo. From then on, Dartmouth diminished the Review's impact by responding to its taunts with moderation. "Whenever a college president speaks out against student journalists, the press will accuse him of quashing their First Amendment rights," said Alex Huppe. "Freedman exercised his own right—in fact, his duty—to comment on the Review. He identified the problem: lack of civility. It was like curing a disease—you start to get a handle on it when the doctor gives it a name. A weight came off the shoulders of the institution, and the faculty felt it. From that point on, most of the responses to the Review's provocations were thoughtful and measured."

Freedman adroitly adroitly shifted attention from the Review's agenda to the paper itself. The Review suffered its harshest bout of public opprobrium in 1990 when on the eve of Yom Kippur, it circulated an issue in which the usual Teddy Roosevelt quote on the masthead was replaced by an anti-Semitic boast from Hitler's Mein Kampf: "Therefore, I believe today that I am acting in the sense of the Almighty Creator: By warding off the Jews, I am fighting for the Lord's work."

It was one provocation more than Dartmouth could abide, and the campus erupted. Led by President Freedman 2,500 students, faculty, and administrators massed on the Green for an open-mike discussion of racism—Dartmouth's largest rally since the Vietnam War. "This has been a week of infamy for the Dartmouth community," Freedman said. A petition denouncing the Review attracted 2,000 signatures in three days.

At a news conference held just before the rally, dinesh D'Souza, by then a trustee of the paper, apologized for the quote. He then accused Freedman of using the incident to silence the Review. "This case is Dartmouth's Tawana Brawlely he told reporters. "You have a sabotage, a hoax, a dirty trick that is being ruthlessly and cynically exploited by the College leadership in order to ruin the lives of many innocent students. President Freedman has emerged as the Al Sharpton of academia."

Within days, the Mein Kampf episode had become a national topic. Congressman Chester Atkins, a Democrat from Massachusetts, collected signatures from 84 colleagues for a letter decrying the incident as "yet another example of this publication's policy of whipping up hate." He appealed to the Review's wealthy patrons to forswear farther support. Freedman himself weighed in with an op-ed piece printed in The New York Times. Distinguished alumni added their own denunciations. Political commentator Morton Kondracke '60 labeled the Reviewers "pre-fascist brats" in The New Republic. Author Theodore Geisel '25, known as Dr. Seuss, sent Freedman the following verse: After reading the Dartmouth Review a disgusted reader said, "Phew! This gift from Bill Buckley is Muckley! It's Uckley! Bill, give it to Yale. O, please do!"

Editor-in-Chief Kevin Pritchett '91 claimed that some unidentified saboteur had surreptitiously inserted the quote. If so, then who? "The question has become the Review's version of who killed Laura Palmer," wrote The nation. The Review itself invited the Anti-Defamation League of of B'nai B'rith to investigate. After more than 400 hours of interviews, the ADL concluded that the quote was slipped into print by an unknown member of the Review's own staff.

More so than in the aftermath of past transgressions, the Review now assumed a defensive crouch. Kevin pritchett wrote a long, conciliatory editorial claiming that the Mein Kampf incident occurred just as he was about to "leap out of opposition into the mainstream. I, more than other editors, had pushed the Review to a place where it no longer had to shock to get its point across; the Review began to use the scalpel instead of the cudgel. The latest controversy, though, has hindered this evolution....There was a need of Perestroika and glasnost at the Review. And I wanted to be the paper's Gorbachev."

The damage was already done. Four of the 24 staffers resigned, including president C. Tyler White '93. "This is in no means a defendable action," he wrote in a letter of resignation. "It is a move of utter hatred. I will not be part of this newspaper anymore."

The surviving Reviewers misplaced their notorious wit when they found themselves on the receiving end. In April 1992, six staff members of The Harvard Lampoon replaced copies of the real Dartmouth Review deposited in dorms with a look-alike parody featuring cover photos of Adolf Hitler posing in the woods in an all-brown shirt by Ralph Lauren, pleated Gurkha shorts by J. Crew, shoes by Armani, and accessories by Victoria's Secret. Then editor-in-chief Kenneth Weissman '93 asked the Dartmouth administration to condemn the spoof. "Hitler is not fanny," Weissman wrote in an editorial. He was apparently unaware that the Review itself had printed a cartoon of President Freedman dressed as Hitler on its cover four years earlier.

In recent years, students have been more inclined to mobilize against the Review. Jud Dean '92 sold stickers that read, "Please do not deliver The Dartmouth Review here." He advertised them as "polite, to-the-point, easy to put on your door, and easy to take off if need be." Three years ago, members of the Black Freshman Forum began confiscating copies after the Review reported the group was having "ugly internal problems." Editor Oron Strauss '95 asked the College to protect the paper's freedom of speech. Dean of Students Lee Pelton refused, arguing that the paper was no different from Other unsolicited matter like menus and fliers dropped at students' doors.

The Review thrived for a decade as a notorious campus bomb-thrower, but it has recently dwindled into a Punchless version of its former self. "A paper that has been around for 15 years is going to develop some institutional momentum, but also some inertia," acknowledged D'Souza. "The quality has been uneven over the years."

Some students read it, but it no longer arouses much heat. "They try to be inflammatory," said Professor Wood, "but you get the impression they're just not as bright. The outrageous idea just isn't there. They haven't come up with any new issues. It's just unimaginative political boilerplate."

"Students don't give it much weight anymore," affirmed Justin Steinman '96, former editor of The Dartmouth. "The Review tries to run incendiary stories but nobody pays much attention. You'd never hear anybody discussing it at lunch."

Did President Freedman precipitate the Review's decline by daring to denounce it? Or did the Review simply succumb to inexorable shifts in political consensus? After all, it's hard for young conservative editors to posture as jeering, defiant outsiders when the G.O.P. controls Congress and conservative authors like Rush Limbaugh, William Bennett, Charles Murray, Ben Wattenberg, and the Review's own Dinesh D'Souza crowd the display windows of Barnes & Noble. "Part of that is coming of age," said former editor Debbie Stone. "The feistiest period for any publication is inevitably the first years, when the battle is fought most enthusiastically. Conservatives have gained some ground, so the Review is no longer the underdog."

With the proliferation of conservative authors, think-tanks, and radio shows, campus conservatives no longer have to shout to be heard. As a result, student papers opened in imitation of the Review are adopting a more moderate, responsible voice. "The most successful ones are no longer confrontational," said Christopher Long, vice president of the Intercollegiate Studies student papers. "They're at their best when they do investigative reporting, as opposed to name calling. It's easy and fun to invoke satire and attack political enemies, but it's no longer advantageous." An example of the less inflammatory reporting style encouraged by the Intercollegiate Studies Institute came two years ago when the conservative Yale journal, Light & Truth, revealed that the university was quietly reneging on its promise to implement courses in Western civilization with a $20 million donation earmarked for that purpose by Texas oil magnate Lee M. Bass because some faculty favored a multicultural curriculum. Bass was unaware of the delay until Light & T ruth broke the story. Yale agreed to return the entire gift. It is believed to be the largest sum ever returned by any university.

What of those precocious editors—the Dartmouth mafia—who entered the capital in the heady Readays intent on dismantling decades of Democratic policy? Their advance publicity won them enviable employment: Dinesh D'Souza got a policy job in the Reagan White House. He later decamped to the American Enterprise Institute, where he wrote the bestselling Illiberal Education. Greg Fossedal wrote editorials for The Wall Street Journal, and earned fleeting notoriety within the Washington press corps for screaming "Answer the question!" at vicepresidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro as she parried with reporters over her husband's tax returns at a 1984 press conference. Michael Jones wrote speeches for Treasury Secretary Donald Regan and Education Secretary William Bennett. Debbie Stone became managing editor of Regnery Gateway publishers. Laura Ingraham clerked for Justice Clarence Thomas and is a political analyst for CBS News and MSNBC.

For all their bold-faced mentions in The Washington Post style section, the Reviewers amounted to a surprisingly inconsequential cohort in Washington's political terms by the time they reassembled at New York's Union Club last year to celebrate the Review's 15th anniversary with dinner, cigars, and an address by their hero, P.J.O'Rourke, who could be described as a cross between H. L. Mencken and Hunter Thompson. Many of the central characters have by now drifted out of the government and policy realm: Greg Fossedal defected to money management. Michael Jones became a Catholic priest. Ben Hart left the Heritage Foundation to run a direct-mail marketing firm.

The Review's tactics have not always translated well to the real world. Hart's wife, Betsy, lost her job at the Heritage Foundation after entering the networking forum her husband initiated carrying a Halloween mask of George Bush's head on a platter splattered with ketchup two nights after Bush lost the election to Bill Clinton. Debbie Stone, now a producer at ABC News, was among four network employees charged last Octover with illegally recording a Baltimore doctor without her permission while preparing a report for the news magazine 20/20. If convicted, she could get a maximum sentence of five years.

According to Stone, the Reviewers' disaffection from Washington's power centers is true to their conservative philosophy: to linger in public-sector jobs would contradict their belief in smaller government. "It's to the Dartmouth Review's credit that it produced people who end up in a variety of fields," she said. "As conservatives, we think the answers don't lie with the government."

Meanwhile, the flamboyant agitators who came of age with Reagan's election have given way to a fresh young face of conservative populism: the 20 something spin doctors, campaign workers, and committee aids who arrived with the new Republican majority on the Hill. Swept in from the heartland on the midterm elections of 1994 and mostly reconfirmed in 1996, they are, for the most part, graduates of small colleges and state universities outside the elite Washington-Cambridge corridor—places like Texas A&M, where Phil Gramm once taught economics, and Regent University, run by Christian Coalition founder Pat Robertson. Unlike those Ivy League conservatives who debated what a conservative government would do in theory, the new crowd concerns itself with the practicalities of enacting Republican policies.

To them, as to many Washington-based conservatives, The Dartmouth Review now amounts to a receding footnote of diminishing import. "The Dartmouth group always overestimated the meaning of their experience to the larger world," said John Podhoretz, deputy editor of The Weekly Standard, the capital's new conservative journal. "Having been at the center of a gigantic controversy that brought in some leaders of the Right, they thought they were on the front lines. In fact, they were just college kids. Their fight was not all that germane once they were in Washington. I was struck by how heavily they involved themselves in the Review years later. They always seemed to be flying up to Hanover to deal with some crisis. They were like former college athletes who think too longingly on their halcyon days."

"THE REVIEW TRIES to run incendiary stories but nobody pays much attention. You'd never hear anybody discussing it at lunch."

"THE REVIEW MADE PEOPLE FURIOUS I mean furious. We realized there are some objectionable people out there, and some are right here in our front yard."

MICHAEL CANELL is a New York-based writer. His work has appeared in The Washington Post Magazine and Sports Illustrated.He is author of a biography of I.M. Pei.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Bunch Of Characters

January 1997 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Feature

FeatureTo the North

January 1997 By Regina Barreca ’79 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

January 1997 By Henry Williams -

Article

ArticleStill on the Freedom Trail

January 1997 By Christopher Kenneally ’81 -

Article

ArticleFootball Gains Perfection While Michigan Gains a President

January 1997 By “E. Wheelock” -

Article

ArticlePaving Paradise?

January 1997 By Noel Perrin

Features

-

Feature

FeatureNoel Perrin Professor of English 2 pigs on a single form

January 1975 -

Feature

FeatureClass Entertainment

MARCH 1991 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Productivity

March 1996 By James Wright -

Features

FeaturesRising Star

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2020 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureThe Growing Threat to Privacy Posed by Computer Data Banks

FEBRUARY 1972 By ROBERT P. HENDERSON '53 -

Feature

FeatureA Tuckerman Tradition

April 1956 By ROBERT S. MONAHAN '29