The Growing Threat to Privacy Posed by Computer Data Banks

FEBRUARY 1972 ROBERT P. HENDERSON '53VICE PRESIDENT, HONEYWELL INFORMATION SYSTEMS

IF there is one lesson to be learned from the past several years of social and political activism, it is that any organization's policy or practice perceived by a significant portion of the population as injurious to the public good will be rectified, usually by government intervention or legislation. Furthermore, it generally holds true that the longer corrective action is postponed, the more expensive such action becomes.

Everywhere the feeling of depersonalization and impotence grows, and many people feel, rightly or wrongly, that it is being brought about by the computer. All of us have heard examples of reputations damaged by erroneous credit reports, computerized voting systems that don't work, or, in the past few months, government dossiers on millions of civilians considered to be possible threats to the national security.

In the past several years a growing number of influential citizens and government officials have begun to publicize the fact that while increased information (and need for computers to process it) is vital to a complex society, there are some inherent dangers associated with this advance in technology. Notably there is a serious threat to the privacy of the individual.

Even the most vocal and vehement defenders of the rights of privacy concede that the computer in itself is not at fault. It is a passive instrument-it can do only what it is told to do by human beings. Therefore what is being urged, and in many quarters demanded, is not the abolition of the computer, but that action be taken regarding the use of computers and their data banks.

By his very nature man is a hoarder of information, particularly about his fellow man. In our complex society, neither government nor business could function without the ability to receive, digest, process and store vast amounts of data. The computer makes this possible.

Each of us leaves an ever-increasing trail of statistical information about himself from birth to death; and in this era of the credit card scarcely a day goes by when the average person does not deposit in some computer's records a business transaction at a store, restaurant or gas station.

Much of the material now being fed into computers and data banks has been on record for years, including data relative to birth, schooling, employment, Social Security, Selective Service, marriage, insurance, courts, hospitals, credit bureaus, churches, clubs and taxes. Many vital decisions regarding jobs, housing, education, and the like are in part determined by the data we have said about ourselves and what others have said about us. (The latter can be especially onerous since in most instances it is all but impossible to find out who said what about us, when or to whom.)

Despite the obvious significance of this storehouse of information about individuals in the possession of unknown third parties, until recently there has been little public concern about it. There were two primary reasons: First, until the advent of the computer, the data was scattered around in many different places among many different organizations. Hence its quantity and use never seemed too threatening. Second, most people are quite willing to tell their life stories (or the life story of a neighbor) to almost anyone who appears to have a quasi-legitimate need for this information.

The past several years, however, have seen a new concern voiced about the volume and availability of these personal files; and the computer is the reason for it. With the computer, and its abilities such as time-sharing and communication with other computers, the old practical limits of time, effort and cost on the size of manual files have been eliminated. The unprecedented efficiency of the computer in storing, processing, manipulating and dissemi- nating information has created central, highly detailed and easily available dossiers on millions of individuals.

In considering the problems that arise from keeping computerized records, many people use the words "privacy" and "security" interchangeably. In fact there is a great deal of difference between the two and different parties must be responsible for each. In his widely read book, Privacy andFreedom (Atheneum: New York, 1967), Prof. Alan Westin described privacy as "the claim of individuals, groups or institutions to determine for themselves when, how and what information about them is communicated to others." In relation to computers, security is the means taken to insure the privacy of the information once it is contained in a data bank. Privacy is a legal, political and philosophical concept and its guarantee properly belongs in the domain of government. Security is a matter of equipment and technique, which is the province of the computer manufacturer. The users of computers should assume responsibility for both privacy and security.

The computer industry today can provide a large number of security devices and systems to guard against the unauthorized use of private information within data banks, and it is working on many more. Such developments have taken place in both the hardware and software areas of electronic data processing. Here are some examples:

Encoding consists of scrambling data transmission so that intercepted messages will be unintelligible unless the interceptor has the code. In principle, data on such storage devices as magnetic tapes or discs also can be in cryptographic form.

A number of security devices, however, are designed to prevent unauthorized persons from getting to the encoded information. These constitute systems requiring positive identification of anyone seeking access to the files and the information in question.

The security of the computer room itself is relatively easy to achieve, and yet many installations make the mistake of maintaining a showplace atmosphere behind plate glass windows. The computer room is not an area for casual visitors or even the mass of employees. Aside from privacy considerations, business and government organizations must keep in mind the danger of destruction of vital records by natural disaster or sabotage.

The best location for a computer room is one of isolation from other work areas. It should be fireproof, of course, and for extra protection all files and programs should be stored in a separate room. Never before has it been possible to concentrate so much vital information about an organization in one spot, so the need for the right location and design is imperative. Once that has been accomplished, the usual protective measures of guards, locks, special passes and badges should be enough to secure the computer room.

The most serious problems result from time-sharing or remote entry systems, where the user of the computer may be working from a terminal many miles away, and hence beyond the control maintained at the site of the computer.

The most common remote security measure today requires passwords to identify a user. Nearly all time-sharing systems use passwords for entry to-day-a vital need in many instances where two or more competitors may be tied into the same time-sharing system and each wants to protect his own files.

A password program can be as simple as an entry code name which can be checked and verified against the computer's files, or as complicated as a long series of questions which only an authorized user can answer—about birthdays, pets' names, grandparents' names, or anything else.

We can also limit not only who has access to a file, but also who can alter a file. The input can also be controlled by designing a format that will accept only certain types of information. A credit bureau or government agency, for example, may be allowed to store information pertaining to age, marital status and income, but not political affiliation, reading habits or health problems. By designing the software to permit only specific data, extraneous information will not be accepted. However, this feature is a function of the user, since software programs designed by the manufacturer can be altered, it is thus the user's responsibility to enforce a restricted software format in order to limit file input.

Nevertheless, a wide variety of ingenious safeguards against unauthorized access via remote terminal is available or under development. The simplest security device is a lock on the terminal so that it will not operate until keys are punched in a special sequence, or a special key or card is inserted into the terminal. More elaborate devices to identify the user, including voice prints, fingerprint scanners and picture phones are under study. Their feasibility and their economics have yet to be positively determined.

A voice print system would work on the principle that a vocal pattern is as unique and personal as fingerprints. A voice can be translated into a code and matched by the computer against authorized voices stored within it. If a match is made, the computer will allow access to the terminal. Fingerprint scanners and picture phones work in the same way. Devices such as these would provide ways in which computer hardware can positively identify a person and match this identification against a file of authorized users.

The data base of a computer's memory can be structured like a tree, with data leaves on its various branches. The system would make security checks on the user at each junction of a branch to the tree trunk. User A, for example, may be authorized for access to only one certain portion of the computer's memory or files of information. When he arrives at that particular junction, his identity will be checked and he will be allowed to examine the data leaves on that branch. If he attempts access to the computers files at any other junction, his identity will not match and he will be denied entry. This system would allow a computer customer to position his checks at various junctions as he desires.

To guard particular critical information, a user might be asked for further identification at the appropriate junction—his mother-in-law's maiden name, for instance.

Another system under development at the Massachusetts Institute of Tech nology, in conjunction with Honeywell employs what are called "rings of protection." In addition to the tree or pyramid structure of conventional data bases the ring structure is built like concentric circles. Thus segments of the system containing sensitive information Scan be placed in a privileged ring together with programs which process, update and extract this information in a carefully prescribed fashion.

A subscriber is allowed to enter a ring only at a carefully defined point, and once he enters the ring the way the information is processed and handled is completely beyond his control; and the user's movements are controlled, i.e. he is prevented from moving elsewhere, even within that ring.

Another feature designed to maintain the security of files is an audit-monitor to record the identity of the person who requested access to information, as well as when and for how long. The auditmonitor system can note abnormal patterns or frequencies of any given file being accessed, and it can record attempts to access a file which were foiled by other security systems.

This is only a sampling of security measures available today or being studied. There are many other devices including signature recognition devices and typewriters which conceal the typed information so that an authorized individual cannot read a password by looking over a user's shoulder.

The problem will not have been solved even when, or if, an absolutely 100 per cent secure system is devised, because ultimately it is the people who operate the system who are responsible.

It was said earlier that the manufacturer of computer systems is responsible for the provision of security devices required to maintain the privacy of the files (or at least to elevate the level of security to the point where the cost of breaking the security is greater than the value of the information being sought, or greater than the cost of more mundane approaches such as bribery). Actually maintaining that privacy is the responsibility of the user. It is thus a fair assumption that if the federal government does act on the problem, it will be to limit or otherwise control the user of computers, the possessor of a data bank, rather than the manufacturer, with the exception of possibly requiring some standardization among the security systems of the various vendors.

It is appropriate to speculate on what the government may demand of the computer user in relation to the privacy issue, and to consider preparatory steps that should be taken now by these users. Such preparation is expedient for several reasons. First, steps taken voluntarily will demonstrate to both government and the public the good intentions of the business community, and hence, business may be in a more favorable position to influence legislation which is designed to control its data processing activities. Secondly, the earlier measures are taken, the less expensive it is to implement them.

The first step the government must take is to define the privacy rights of individuals in terms of today's technology. There is no real precedent in our history for the situation as it exists now, and in fact the Constitution of the United States does not mention privacy by name. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to assume that any legislation regarding privacy would have the effect of extending those other rights guaranteed in the Constitution.

The first amendment in the Bill of Rights guarantees freedom of speech and association. The fourth amendment states, "The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated . . ." The fifth amendment has potential bearing on the situation; it forbids that "private property be taken for public use without just compensation." The fourteenth amendment prohibits any state from depriving "any person of life, liberty or property without due process of law." It is not unreasonable to assume that personal information is covered under "life, liberty or property," and the right to be secure in one's "person, papers and effects" extends to personal data.

After defining the right to privacy, the single most effective measure to protect that right would be legislation allowing each person access to his own file, wherever it may be kept; for the knowledge that a person could view and challenge his file in the courts would deter the keeper of the file from irresponsible action. Such an action would mean a complicated set of procedures for business, but such legislation appears all but inevitable. Procedures must be worked out for notifying an individual that a firm has a file about him, for allowing the person to examine this file and change erroneous information, for informing him when and to whom the information in the file is being released, or for securing the person's permission before the information is released.

Other legislation likely to be considered in the next few years would have the effect of (a) controlling the nature of the system itself and/or (b) controlling the people who work with the systems.

To consider the second case first, the staff of a data processing department is still the weakest link in a security chain, for it is the staff that has the technical ability and the best opportunity to tamper with the system or secure sensitive information. Because of this fact, some form of certification of computer operators and systems designers may be required by the government, much like accountants, lawyers, doctors, plumbers or electricians are certified. Such a measure is desirable from many points of view. Because people are vulnerable no matter how secure the system, it is imperative that staff members be well qualified and, because they would be certified, easily identifiable. Secondly, certification of computer operators places no burden on the businessman, other than to make sure those data processing people he hires are certified.

In addition to certifying the people, it is possible that some steps will be taken to insure that the system itself is certified, and an institution would not be allowed to operate a data bank without certification. The computer, as mentioned, is the focal point for the privacy issue, and the reason is the computer's ability to reorganize a large quantity of information, each element of which is separately harmless, into a more meaningful collection of information which together may reveal more than desired. Thus, one aim of system certification would be to set requirements on the input to a computer's data base. For example, the identity of the supplier of each bit of information in a person's file could be required, along with the dating of all entries.

System certification would also have the effect of requiring the possessors of data banks to implement many of the security devices and systems mentioned earlier.

There are literally two directions in which computerized data banks can take us. One leads toward a radical realignment of knowledge and power where the controlling interests have little or no regard for human values. Its end will be a goldfish-bowl society in which any individual's activities may be recorded and scrutinized.

The other path enlists computers in expanding knowledge for the benefit of all, using the power of computers to help cope with the complexities of modern life.

A great deal can be done to make progress along the right path, regardless of what government does. Users of computers must exercise a special sensitivity in selecting the personnel who have access to the data banks; for no matter how secure the system, there is always the danger of people being compromised. Trained, dependable people are an absolute necessity in the matter of privacy and security.

Another relatively easy and inexpensive step that can be taken now is conducting periodic audits, by either internal or external groups, to determine what information is contained in the data bank and weed out plainly outdated and irrelevant data.

The most effective step for every user is to exercise concern over the matter of privacy and security at the very beginning of the system design stage. Building concern into the system at the design stage is more effective and more economical than adding devices or altering the system after installed.

Lastly, we must have increased public awareness of both the blessings and dangers of a computerized society, for there is the risk that a little bit of knowledge on the part of the public and legislators will lead to action that is not in the best interests of the country. Before laws are passed regulating computer systems a thorough understanding of the nature and technology of data banks is needed, and the efforts of the computer industry and the users of computers are vital to bringing about such an understanding.

Computers are essential to the efficient conduct of our complex world, but like every technological advance, they can be used destructively. The time is already short for business and government to join in developing controls to insure that they aid, not damage, our democratic freedoms.

Only through an honest, concerted effort can we hope to avert the danger that 1984 will arrive before its time.

"Computers are essential to the efficient conduct of our complex world, but like every technological advance, they can be used destructively. The time is already short forbusiness and government to join in developing controls toinsure that they aid, not damage, our democratic freedoms."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEDITING ROBERT FROST

February 1972 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Meet with Alumni Council

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSymphony Conductor

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureExecutive Exporter

February 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSnow Engineer

February 1972 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1972 By MARK HELLER '70

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Very Laid-Back Place"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Feature

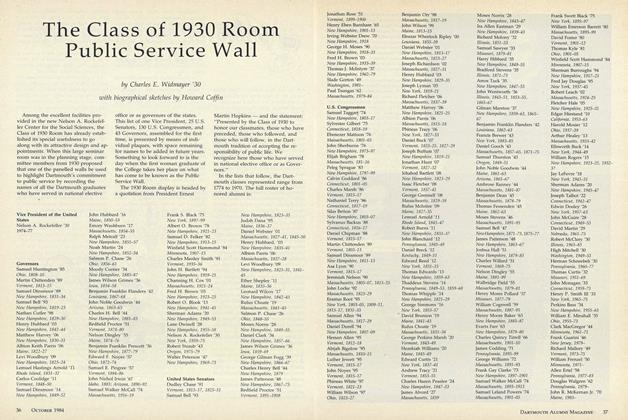

FeatureThe Class of 1930 Room Public Service Wall

OCTOBER 1984 By Charles E. Widmayer '30 -

Feature

FeatureFie on the Flush Toilet

NOV. 1977 By Harold H. Leich -

Feature

FeatureSoldiers As Policy Makers

February 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOur Altar

APRIL 1997 By MARIANNE CHAMBERLAIN '93 -

Feature

FeaturePeace Corps Professor in Bolivia

DECEMBER 1965 By ROGER C. WOLF '60