All, the aesthetic joys of Dartmouth: The Green,the elms, the concrete, the jackhammers.

I don't think I've been curmudgeonly enough lately. I've hardly grumbled at all, still less moaned about how much better things used to be in the old days. Well, this month I am going to make up for it.

There is too much damn cement the Dartmouth campus. All those sidewalks! Sometimes there are three or four to a building. If you doubt me, take a stroll in front of Parkhurst Nutt, Robinson, Collis It looks Mike someone who owned a cement mixer decided to get into the Earth Art business, and picked our campus to practice on.

You don't find a zillion cement sidewalks at Oxford or Cambridge; you find well-kept gravel paths. Only on the actual Green is this true at Dartmouth. Even on the Green there's already a big metal air vent rearing its ugly head, and most of the year making a sibilant noise like a sick dragon. Of course you don't find mud season at Oxford or Cambridge, either, and I readily concede that there needs to be some way of getting around campus in March and April that doesn't involve a pound of mud on each shoe.

But why cement? Cement has not one but three disadvantages. First, it's too damn permanent. Once you pour a stretch of cement sidewalk, the only way to get rid of it again is with a backhoe if you're taking out the whole stretch, or jackhammers if you're just cutting across to make a trench for a new steam tunnel or computer lines or new sewer pipes. Dartmouth being a vigorous place, someone is practically always cutting through a sidewalk to accommodate some new thing. The noise, especially during a class in Dartmouth Hall or Reed, makes you homesick for dragons with a death rattle, or maybe the battle scenes in B movies about World War II.

Why couldn't we nave beautiful slate sidewalks around campus? Both Vermont and New Hampshire are slate country; there are numerous slate quarries in the region. We could get big heavy slates, ones that would hold up to the admittedly heavy traffic of riding mowers in the spring and summer, leaf blowers in the fall, tractors with chains and plow blades in the winter. Then, when you needed to put in a new line somewhere, no jackhammer needed. Take up one slate. Put the new line in. Replace the slate.

Second, cement tends to stay at its original elevation, while the grassy earth on both sides very slowly rises. After enough years you have a situation like that on both sides of the Green, and on much of the cement walk going down to Tuck and Thayer. The sidewalk is half an inch to an inch below ground level, and so in mud season whole stretches are covered half an inch deep in water. The students mosday wear boots to class. I've seen faculty carrying office shoes in a little bag. Visitors in city garb can be seen halted before an especially large puddle, obviously debating whether to splosh through it or to go round on the muddy and half-frozen edge.

The same thing would happen with slates, of course—but slates are adjustable. They can, as we say, go with the flow. If the sidewalk in front of Dartmouth Row were made of heavy slates, and if the ground level got higher, you'd simply lift each one for a minute and put down a little sand. You could do the whole stretch in one day. No jackhammers needed.

Third disadvantage. Cement is—no, not ugly. Cement is less beautiful than stone or brick. It is more beautiful than asphalt sidewalks, which obscenity we have mostly been spared. One of the saddest urban sights I know can be seen in vari-ous ous parts of Boston, where a fine old brick sidewalk has been patched with asphalt. No patches here, though there is a homely little asphalt sidewalk on the north side of Wheeler dorm. It's almost grubby enough to make a Bostonian feel at home.

Aesthetically, it's perfectly bearable to have all that cement. But joyful it's not. Visitors and students alike, we delight in white-painted brick buildings with trompe I'oeil windows that get smaller on each successive floor. We delight in the Green, in Baker Tower, in the great elms it takes such skill to keep alive, in the Inn and Casque & Gauntlet looking at each other across the Inn corner. But I've never heard anyone say, "Oh, look at all those pretty cement sidewalks."

Of course, even if someone had, I might not have heard it. Between the tourist buses that park by the Inn with their high-pollution diesel engines running, the crews out with jackhammers, the shrill cry of trucks backing up, I miss a lot.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

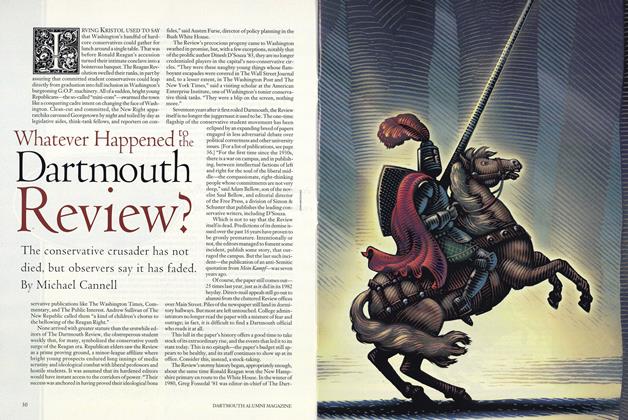

FeatureWhatever Happened to the Dartmouth Review?

January 1997 By Michael Cannell -

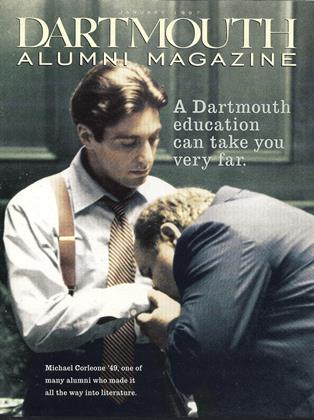

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Bunch Of Characters

January 1997 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Feature

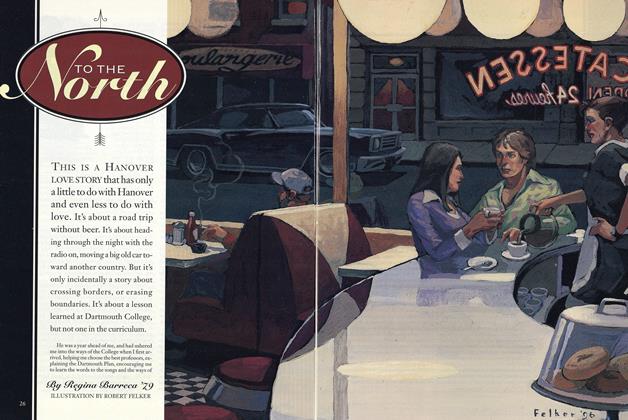

FeatureTo the North

January 1997 By Regina Barreca ’79 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

January 1997 By Henry Williams -

Article

ArticleStill on the Freedom Trail

January 1997 By Christopher Kenneally ’81 -

Article

ArticleFootball Gains Perfection While Michigan Gains a President

January 1997 By “E. Wheelock”

Noel Perrin

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

MARCH 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThe College in the Suburb

May 1974 By NOEL PERRIN -

Feature

FeatureAn Environmental B

Winter 1993 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleMinor Issues

MAY 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleHonor by Degrees

MAY 1997 By Noel Perrin -

CURMUDGEON

CURMUDGEONBring Back the Vox!

Sept/Oct 2000 By Noel Perrin