THIS IS A HANOVER LOVE STORY that has only a little to do with Hanover and even less to do with love. It's about a road trip without beer. It's about heading through the night with the radio on, moving a big old car toward another country. But it's only incidentally a story about crossing borders, or erasing boundaries. It's about a lesson learned at Dartmouth College, but not one in the curriculum.

He was a year ahead of me, and had ushered me into the ways of the College when I first arrived, helping me choose the best professors, explaining the Dartmouth Plan, encouraging me to learn the words to the songs and the ways of this particular world. Protective of me and defensive of the place, he had a tough role to play. Even though we had known each other for years, we knew only those things one knows from classes and meetings; we knew one another casually and intimately at the same time. I knew how much milk to put in his coffee, for example, and he knew I didn't like to call him at his fraternity house for fear of hearing one of the brothers bellow my name up the stairs to him. But I didn't know whether he snored and he didn't know whether I slept in a T-shirt, a nightgown, or nothing at all. I had occasionally tousled his hair as I passed by him, half reading in Sanborn House, and he bought me flowers on my birthday when everyone seemed to have forgotten. At his fraternity house door late one night, ignoring the noise, I cried to him over the loss of some other man, and he held me at arm's length. I wonder whether to focus on the fact that I was held, or that I was held at a distance.

We had no anniversaries to share or reason to kiss except to say hello after the absences caused by vacation or a term away, or goodbye before parting at holidays. So, then, we didn't kiss. We didn't date. We were friends.

We became even better friends after he got a girlfriend at Smith, because we were positioned on a level playing field. I smiled more deeply into his eyes, and he permitted himself the occasional compliment about my clothes or expression. I liked the girlfriend in part, I admit it, because in a comparison between us two I had a reasonable edge. She was adorable but not quick; she was devoted, which meant she lacked the appeal of an established emotional distance, the appeal of independence.

So we were all right, up to a point. But then I began to wonder whether I'd begun overdoing it lately, calling too much or leaving too many messages on his door, telling him too many stories and laughing too hard at his jokes. But his jokes were a narcotic to me, and I longed to tell him what happened to me every day. Increasingly he became the receiver of my imaginary conversations, my running commentary of the daily routine was directed toward him.

When spring came, he didn't return my phone calls for a few days, and I started to worry. I ran into him on the way to the library one night and, barely touching his arm, asked him whether he was pissed off at me or annoyed or upset or anything. He looked genuinely and Gratifyingly horrified; his eyes widened and he said no, no, why did I think that? He said that if he didn't call back right away it was only because he was busy—and then he said, "Let's go. We've been in Hanover too long. Let's blow this taco stand."

The 1968 Monte Carlo was in its usual illegal space behind the house. We got in and headed north. The signs for towns in northern New Hampshire got brighter as the sun started to set. The car had a tape deck, perhaps something stolen and installed by a rogue cousin in Providence. We listened to Steely Dan and Bruce Springsteen and patti Smith. I sang loudly and off-key but I knew all the words. He had a voice like traffic, rough and low, and he knew all the words, too. The car had those long slick bench seats and before we were at the border I dared myself to slide over, tucking under the long arm he had outstretched across the back. He didn't seem to notice. We kept singing, looking for luck and signals in the songs. We felt like engines that had lost their driving wheels, we knew that the door was open but the ride wasn't free, and we knew that the night belonged to lovers. We sang so that we didn't have to speak, and we didn't want to speak because anything we would have said, as the white lines moved faster beneath the dark wheels, we would regret later. It was simple between us, but that didn't mean it was easy. Confused desire complicates what is simple.

At the border we told the skeptical but lazy guard that we were visiting to look at graduate schools the next day, that we had interviews, that we were engaged. He didn't ask questions, which in a way was too bad: the fiction we'd created was an alternative universe, a virtual relationship, a life we could have been living except for the fact that we weren't.

We went looking for a place to eat just before midnight, walking through the cold clear streets of brightly lit Montreal. He started singing "Mack the Knife" using only the first line of the song, singing the same words over and over again: "When the shark bites, oh the shark bites, and that sharks bites, see the shark bites..." We laughed, and I put my thumb into the belt loop over his hip, feeling the slight limp in his walk from a hockey accident the winter before. We found a kosher delicatessen and ate huge smoked-meat sandwiches, sharp pickles, and Knishes that steamed when you broke them open. We sat at the counter, looking at each other out of the corners of our eyes, and talked to the waitresses in bad French. We told them we were getting married in June and that we were both applying to graduate school at McGill. They told us which neighborhoods would suit us best. They giggled, conspirators in our elopement plans, and poured coffee into our cups as if it represented their good wishes. We said goodnight to the waitresses around two a.m. and walked into the now chest-clenching cold of a star-filled night.

We knew our options. We knew there were hotels, we knew there was the Monte Carlo with its bedroom-sized seats. We knew there was the ease of walking hip to hip. And we knew it wouldn't work. Not when we had to face each other in Sanborn House. Not when we still needed to talk about classes, and plans, and a future that included other people. And so we began to drive back.

It was daybreak when Hanover appearede, Main Street scrubbed white with sun and just waking up. We sat in the car for a few minutes. I intended to leave abruptly. say goodnight and go, but instead I sat. I was afraid he wanted me to leave quickly; I thought of asking him to drive around a little more. But I knew I couldn't. So we sat and I moved, half-consciously, toward him. There was no music now. He asked, expressionless, "You staying or going?"

With that said, the texture of the air changed, a shift in our mutual cogs, something unlocking and then quickly relocking in ourselves. I reached over to put my hand on his and he covered it with both his hands, raised it to his warm mouth. He kissed the inside of my palm, briefly. There was no better time to go.

to let myself be thinned, like paint, to be applied more easily to him. He couldn't have given up skiing and hockey, wouldn't have wanted to compete all day at school and come home only to continue the battle, exhilarating as it was. We were linked not by destiny but by circumstance. We had the College in common, and we were afraid to find out if there could be something else. The friendship had to be more enduring, we figured, than any other version of ourselves.

But I wonder now whether that was true. The friendship buckled, finally, under marriages and kids and distance and these grown-up lives of ours; I don't know where he lives or what he thinks about. And yet there was something put away during that night trip up north, something in self-storage, kept from the wear-and-tear of everyday life, still keeping the edges of it sharp and clear.

Felker '96

The Waitresses giggled, Conspirators in our elopement plans, and poured coffee into our cups as if it represented their good wishes.

Contributing editor REGINA BARRECA'S Latestbook is The Penguin Book of Women's Humor.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

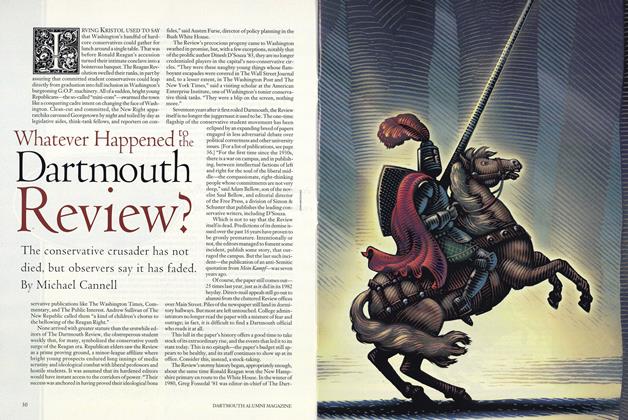

FeatureWhatever Happened to the Dartmouth Review?

January 1997 By Michael Cannell -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Bunch Of Characters

January 1997 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1952

January 1997 By Henry Williams -

Article

ArticleStill on the Freedom Trail

January 1997 By Christopher Kenneally ’81 -

Article

ArticleFootball Gains Perfection While Michigan Gains a President

January 1997 By “E. Wheelock” -

Article

ArticlePaving Paradise?

January 1997 By Noel Perrin

Regina Barreca ’79

Features

-

Feature

FeatureEngineering in the Limelight

NOVEMBER 1971 -

Feature

FeatureELECTRIC BODY LANGUAGE

SEPTEMBER 1991 By JAY HEINRICHS -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

July/Aug 2013 By Mark Brosseau ’98, Mark Brosseau ’98 -

Feature

FeatureSteady State

September 1976 By Pierre Kirch -

Feature

FeatureMaking the Normal Less Normal

NOVEMBER 1989 By Warner R. Traynham '57 -

Feature

FeatureCan Chinese Civilization Survive Communism?

November 1959 By WING-TSIT CHAN