I don t see you; Therefore you don't exist.

THE SUMMER I WAS 19, I spent a full day in charge of a four-year-old cousin. You couldn't call it baby-sitting: David was no baby, and I certainly didn't get to sit.

Here was the situation: A whole bunch of relatives were staying in a big old summer house owned by one of my uncles. One day, nearly everybody went off, some to look at antiques, others home to write. She offered me a handsome fee to spend the day minding her son.

I minded him, all right, and by mid- afternoon Iwas exhaust. He never stopped talking, and he was not afraid to repeat himself. "But why can't we go canoeing?" he was asking for about the tenth time when I got my bright idea.

"David, I can't hear you," I said.

There's no point in asking about the canoe, because I can't hear a word you say." David put his mouth about six inches from my ear. "Canoe!" he shouted. "Sorry," I said. "I didn't hear a thing. As a matter of fact," I added thoughtfully, "you don't even exist."

"No, you don't. I can't see you and I can't hear you."

Give David credit. He now reinvented the tactic that Dr. Samuel Johnson used 200 years ago to refute Bishop Berkeley. Berkeley claimed that nothing exists, at least as matter. To refute him, Dr. John son kicked a stone. David, more enterprising, kicked me. It hurt, too. But I just smiled. "I didn't feel a thing," I told him. "That's because you don't exist."

David burst into tears, and ran into the house. Soon he emerged with his mother, still sobbing. "Make him say I exist," he demanded.

What has this story to do with Dartmouth? A lot. Dartmouth students often play the role I did that summer afternoon. Residents of Hanover and Lebanon play the role of David. And it creates a certain amount of hard feeling.

Here's the situation: Central Hanover is, as it should be, designed for pedestrians. There are 11 pedestrian crosswalks around the Green alone.

If you happen to be driving through Hanover at a moment when a class period ends, all of a sudden there are hundreds of students streaming across the roads. Most stay on the crosswalks, but not all. There are times—say, a few minutes after 11 o'clock on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays—when cars may have to wait a full minute before they can ease through a busy crosswalk. Fifty or a hundred yards later they get stopped at another crosswalk full of students.

That Hanover favors both pedestrians and bicyclists is as it should be. It's fair and proper that half a dozen cars, each with a single occupant, should wait while 50 or a hundred students cross the road. It's fair even if there are also big trucks, and even if they have to wait a whole minute.

But how I wish there were one change in student behavior. I wish they would acknowledge the stopped cars and trucks— wave, or smile, or at least not saunter.

Many students do wave or smile, especially those who are cutting across where there is no painted crosswalk, such as the hundred-yard stretch of Main Street before the Inn corner. Some will even politely break into a trot, thus sending a courteous signal of awareness to the drivers.

But there are many others who look neither right nor left, who saunter, who seem not to notice that the cars and trucks exist. I don't think there's any particular arrogance or snobbishness involved, though there probably is some subconscious awareness that the town is here for the sake of the College, and not vice-versa.

This is no major problem. It's tiny. Still, the older I get, the clearer it becomes to me that true politeness has this at its core: It gracefully acknowledges the existence of other people.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

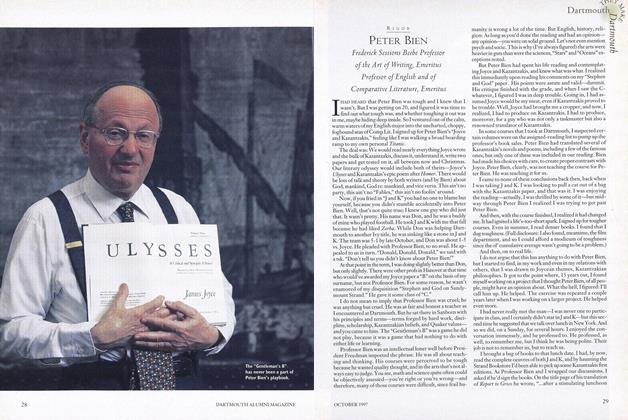

Cover StoryPeter Bien

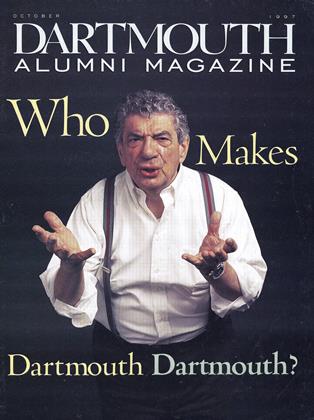

October 1997 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryM. Lee Pelton

October 1997 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Cover Story

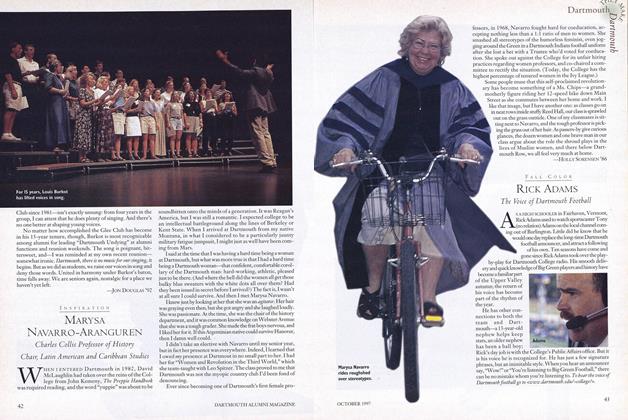

Cover StoryMarysa Navarro-Aranguren

October 1997 By Holly Sorensen '86 -

Cover Story

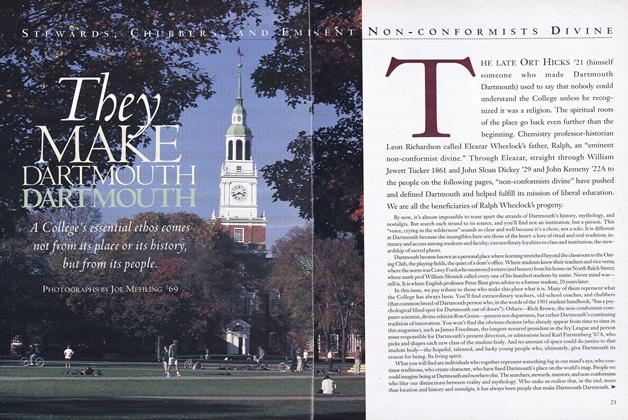

Cover StoryThey Make Dartmouth Dartmouth

October 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWilliam Cook

October 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChris Miller '97

October 1997 By Jake Tapper ’91

Noel Perrin

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JAN./FEB. 1978 -

Article

ArticleThe Prize Nobody Wins

JUNE 1978 By NOEL PERRIN -

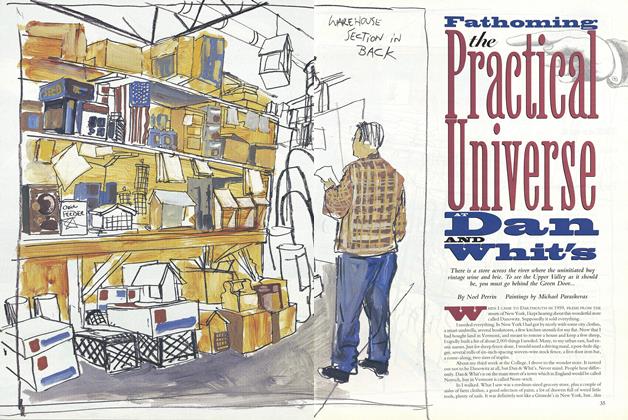

Feature

FeatureFathoming the Practical Universe Dan and Whit's

April 1995 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleOffice Hours

JUNE 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleUntenured Gems

JANUARY 1998 By Noel Perrin -

CURMUDGEON

CURMUDGEONSkating on Thin Ice

MARCH 2000 By Noel Perrin