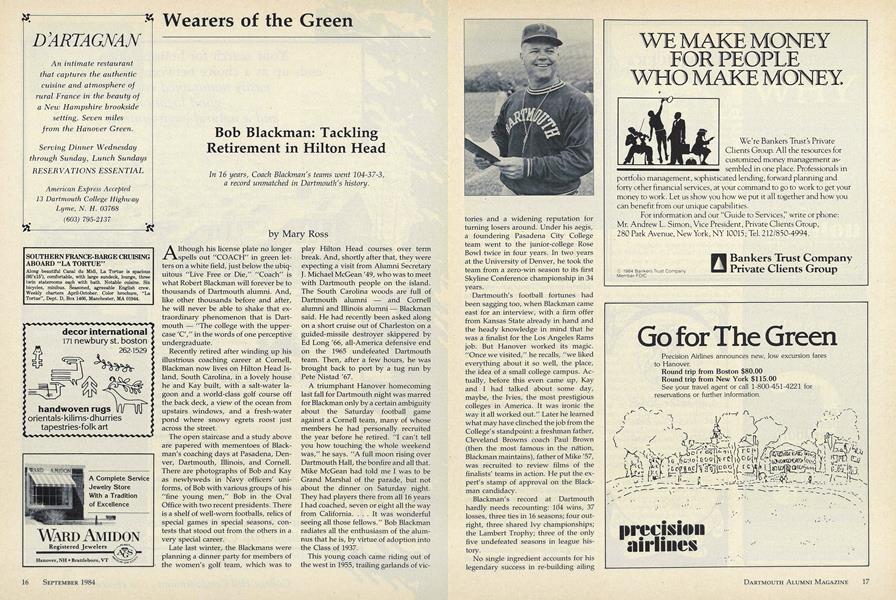

In 16 years, Coach Blackman's teams went 104-37-3, a record unmatched in Dartmouth's history.

Although his license plate no longer spells out "COACH" in green let- ters on a white field, just below the übiq- uitous "Live Free or Die/' "Coach" is what Robert Blackman will forever be to thousands of Dartmouth alumni. And, like other thousands before and after, he will never be able to shake that ex- traordinary phenomenon that is Dart- mouth "The college with the upper- case 'C'," in the words of one perceptive undergraduate.

Recently retired after winding up his illustrious coaching career at Cornell, Blackman now lives on Hilton Head Is- land, South Carolina, in a lovely house he and Kay built, with a salt-water la- goon and a world-class golf course off the back deck, a view of the ocean from upstairs windows, and a fresh-water pond where snowy egrets roost just across the street.

The open staircase and a study above are papered with mementoes of Black- man's coaching days at Pasadena, Den- ver, Dartmouth, Illinois, and Cornell. There are photographs of Bob and Kay as newlyweds in Navy officers' uni- forms, of Bob with various groups of his "fine young men," Bob in the Oval Office with two recent presidents. There is a shelf of well-worn footballs, relics of special games in special seasons, con- tests that stood out from the others in a very special career.

Late last winter, the Blackmans were planning a dinner party for members of the women's golf team, which was to play Hilton Head courses over term break. And, shortly after that, they were expecting a visit from Alumni Secretary J. Michael McGean '49, who was to meet with Dartmouth people on the island. The South Carolina woods are full of Dartmouth alumni and Cornell alumni and Illinois alumni Blackman said. He had recently been asked along on a short cruise out of Charleston on a guided-missile destroyer skippered by Ed Long '66, all-America defensive end on the 1965 undefeated Dartmouth team. Then, after a few hours, he was brought back to port by a tug run by Pete Nistad '67.

A triumphant Hanover homecoming last fall for Dartmouth night was marred for Blackman only by a certain ambiguity about the Saturday football game against a Cornell team, many of whose members he had personally recruited the year before he retired. "I can't tell you how touching the whole weekend was," he says. "A full moon rising over Dartmouth Hall, the bonfire and all that. Mike McGean had told me I was to be Grand Marshal of the parade, but not about the dinner on Saturday night. They had players there from all 16 years I had coached, seven or eight all the way from California. . . . It was wonderful seeing all those fellows." Bob Blackman radiates all the enthusiasm of the alumnus that he is, by virtue of adoption into the Class of 1937.

This young coach came riding out of the west in 1955, trailing garlands of vie Tories and a widening reputation for turning losers around. Under his aegis, a foundering Pasadena City College team went to the junior-college Rose Bowl twice in four years. In two years at the University of Denver, he took the team from a zero-win season to its first Skyline Conference championship in 34 years.

Dartmouth's football fortunes had been sagging too, when Blackman came east for an interview, with a firm offer from Kansas State already in hand and the heady knowledge in mind that he was a finalist for the Los Angeles Rams job. But Hanover worked its magic. "Once we visited," he recalls, "we liked everything about it so well, the place, the idea of a small college campus. Actually, before this even came up, Kay and I had talked about some day, maybe, the Ivies, the most prestigious colleges in America. It was ironic the way it all worked out." Later he learned what may have clinched the job from the College's standpoint: a freshman father, Cleveland Browns coach Paul Brown (then the most famous in the nation, Blackman maintains), father of Mike '57, was recruited to review films of the finalists' teams in action. He put the expert's stamp of approval on the Blackman candidacy.

Blackman's record at Dartmouth hardly needs recounting: 104 wins, 37 losses, three ties in 16 seasons; four outright, three shared Ivy championships; the Lambert Trophy; three of the only five undefeated seasons in league history.

No single ingredient accounts for his legendary success in re-building ailing football programs or none, at least, that he's willing to pinpoint. "Success in college football is a combination of so many things," he says. "Part of it is just plain knowledge of the game and a thirst to know more. Every year, for instance, I'd go visiting other teams' spring practice, and summers I'd go to pro camps. Part of it is always to be working to motivate the young men you're coaching; part of it is compatibility with faculty and the administration; another part is garnering the help of alumni. So many things have to fit together."

"Fortunate" is a big word in Bob Blackman's lexicon. So is that phrase, "fitting together," or its kin, "things happening to go right." He was fortunate to have a couple of national championship junior-college teams at Pasadena; everything happened to go right at Denver; it was his good fortune to coach three undefeated teams at Dartmouth, where he was also fortunate in hiring a fine young coaching staff, 16 of whom went on over the years to become head college coaches. In each place, it seemed to be the right time. One might wonder why fortune rarely smiles on other coaches as consistently as on Bob Blackman, or that things happen to go right quite as often for him.

He has had his share of frustrations too. When he left Dartmouth for the big time and the Big Ten, he worked his miracles at Illinois, but not with the same measure of success he (and his fans) had become accustomed to. In his first season with the not-so-fighting Illini, a team that had won only four games of the previous 30, he suffered six defeats in a row before going on to knock off the next five opponents, all Big Ten. (It had been almost 20 years since Illinois had taken five in a row, more than 25 since they had won a series of five against Big Ten rivals.) But the championships eluded him, the University of Michigan and Ohio State goliaths always looming above, an obstacle to records and recruiting, even home-state players. "I guess I'd been spoiled, having the good fortune wherever I'd been of winning championships," he concedes.

Blackman is the first to admit the sort of pressure that goes with the job he had aspired to since boyhood. "There's so much pressure in coaching," he admits, "and it doesn't come from the alumni or from the downtown quarterbacks or from the newspapers. The greatest pressure is self-imposed. You become so emotionally involved with the young men you're working with, so appreciative of the sacrifices they are making working out after classes in the spring and after the day's work at summer jobs, giving up a couple of weeks' pay at those jobs to come back early for practice. You want so desperately to win for their sakes. It kind of gnaws away at you.

"Nobody," he adds ruefully, "ever taught me how to relax during football season."

At last January's annual meeting of the American Football Coaches Association, which Blackman has served as both president and trustee, Tom Landry of the Dallas Cowboys offered his colleagues a startling statistic: of all the head coaches in the country, pro and college, an average of only one a year reaches retirement age still coaching. The rest, Landry told them, either burn out, get fired, or opt for greener, more tranquil pastures. It was an impressive ratio, Blackman recalls. "I've been fortunate," he says cheerfully, "to be able to do what I wanted all 40 years, right through to retirement." Despite the pressure, the recruiting trips, the 13-hour Sundays spent studying Satur- day's films, "I loved it all; I have no regrets."

Bob Blackman has tackled retirement with all the energy and the ebullience he has applied to everything else in his life. "For years I've heard people talk about what a tough transition it would be, wondering what you're going to do with yourself. But it's the easiest thing I've ever done," he maintains. "There aren't enough hours in the day. We ride our bikes, fish in the lagoon, and I play golf almost every day." (The Blackmans' children seem to approve of their parents' choice of a retirement home: Julie works on Hilton Head, and Gary '68, an avid fisherman, comes on visits from Washington, D.C., where he is athletic director at Sidwell Friends School.)

One thing he will always have time for is Dartmouth, insists Blackman, who, at the time of this interview, was already planning a trip north for the April dinner in Boston honoring the Big Green's sports greats. "No question, as we look back on a whole lifetime, I think Kay and I feel our 16 years in Hanover were the happiest time. But when we left, it was time to leave.

"I had so much respect for John Dickey, and I was so shocked when he announced his retirement. Then, when he said he felt that one man shouldn't be in one position for too long a span, it made me do a little thinking. I have no regrets about leaving; it was time to make a move. But," adds Robert L. Blackman ad'37, "Dartmouth will always be in my heart more than any other place." W

"Nobody ever taught me how to relax during football season."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

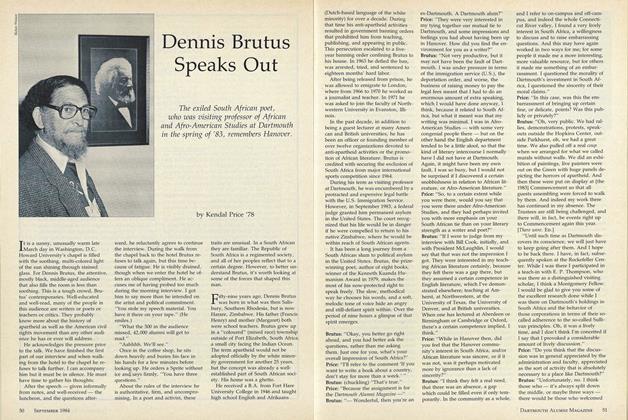

FeatureDennis Brutus Speaks Out

September 1984 By Kendal Price '78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Montgomery Endowment Finds a Home

September 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureRichard Eberhart at Eighty: The Long Reach of Talent

September 1984 By Jay Parini -

Feature

Feature"Three ... Forty-two ... Hut"

September 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

Feature"Innocent Ardor and Delight": A Tribute to Richard Eberhart

September 1984 By James Melville Cox -

Article

ArticleRumblings On Fraternity Row

September 1984 By Fred Pfaff '85

Mary Ross

-

Feature

FeatureThe Nautical Nyes

MAY 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticlePrairie Ornithologist

NOVEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureEgyptologist

DECEMBER 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureEditors' Editor

JUNE 1973 By MARY ROSS -

Article

Article300 Million Years Ago . . .

NOVEMBER 1981 By Mary Ross -

Article

ArticleBiathlete

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Mary Ross